CLIFFORD, THE BIG RED DOG: Published February 4, 1963

Growing up, I was always “the big kid” – and not by a small margin, either. I tended to tower over the kids my own age, and unlike a lot of tall people, I was not a “beanpole”. I was also large and endomorphic – the kid who wore adult-sized clothes before he left elementary school. I spent my first two decades with people assuming I was much older than my actual age. There was a disturbing common reaction when they discovered I was younger than they imagined: they assumed I was mentally incapacitated. I was a teenager when I recognized that the comments and insults hurled at me were all rooted in the belief that excessive size indicates a mental deficiency. (Think Lenny from Of Mice and Men, a comparison I’ve heard more than a few times in my life.)

Yes, I was overweight, but I was also just a very large person. For instance, today I have a size 8-3/8 head. For reference, hatmakers stop making hats at size 8, while the smallest hat size is 6-5/8. My head is several standard deviations above the mean. I cannot wear hats, and they don’t make motorcycle helmets that fit me. So much of my size is just a result of a genetic happenstance, not something I could have controlled in any way. And yet, the taunts and jibes I’ve heard throughout my life tend to focus on my size as a moral failing. It’s as if people believe that only a stupid and self-destructive person would ever let himself grow this large. And for years, that illogical position always stung. Deeply.

When my kids were young, some of the things they loved were new to me. But my favorite things were the things that I had also loved as a child. Things we could truly share. Like Sesame Street. I Am A Bunny. The Muppets. Frog & Toad. And the one that spoke to my over-sized physical existence more than any other, Clifford, the Big Red Dog.

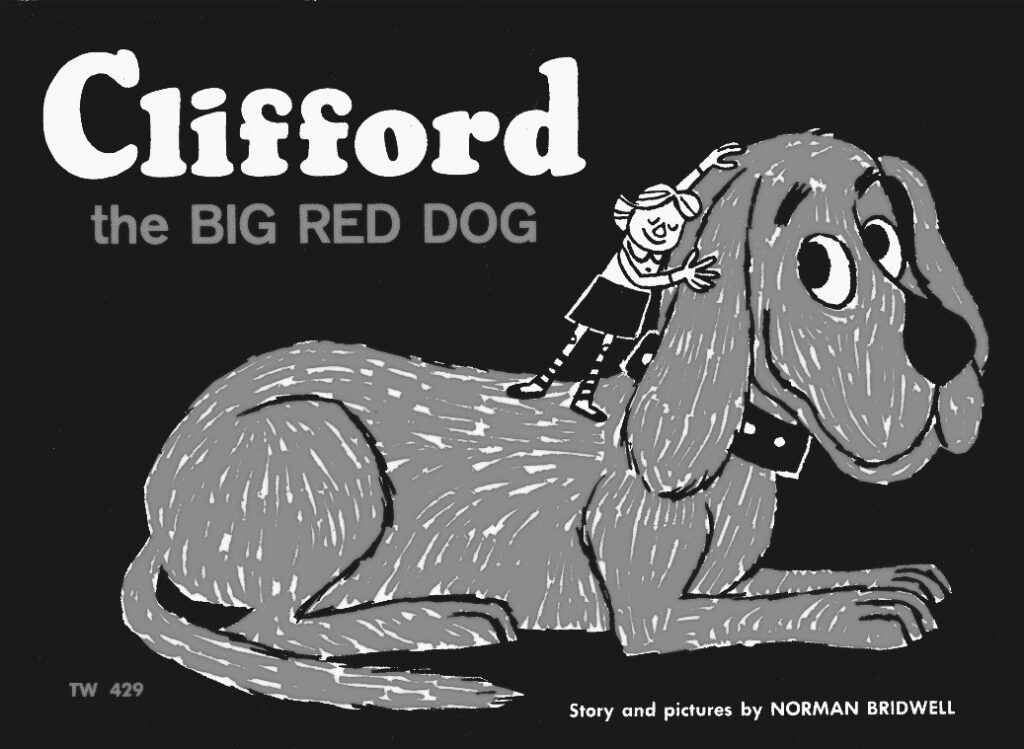

In 1962, Scholastic Books was a struggling publisher that focused on books for young readers. They followed a direct marketing approach to book sales by offering catalogs and book sales in elementary schools, but they lacked a foundational book series to help them compete with Golden Books. Norman Bridwell had been a struggling children’s book illustrator for a few years when an editor looked over some of his paintings of a horse-sized dog and suggested he write some stories to go along with the paintings. Bridwell followed her advice and wrote the story of Clifford, the Big Red Dog. He submitted it to Harper & Row (his previous publisher), but they rejected it. But a keen-eyed reviewer at Harper & Row passed it on to Scholastic. Scholastic knew the book was just what they needed. In 1963, Clifford, the Big Red Dog was released and became an instant hit with young readers. Soon, there would be dozens of Clifford books, and the big red dog would become the mascot for Scholastic Books (and remains their mascot to this day).

It is interesting to see how strongly people liked Clifford since the big red dog in the first published book was far different from the way Bridwell had written him in early drafts. Originally, Clifford was just a fairly-large Viszla dog. In Bridwell’s mind, he wanted Clifford to be the size of a horse, with the reddish-brown fur of an Irish Setter. Bridwell wanted to name the dog “Tiny”, which was – quite frankly – a little hacky. But by the time Clifford, the Big Red Dog was published, Clifford was enormous – larger than a two-story house. And Bridwell wanted him to be a less-nuanced color, preferably one of the primary colors. Bridwell just so happened to have a bunch of extra red paint lying around. And so Clifford, the Big Red Dog was born.

And he was unlike anything anyone had ever seen before.

The study of the human brain tells us a lot about how our ancestors evolved in the face of change. Thousands of years ago, when humans lived exclusively in small tribes, it was critical for our brains to recognize if the person (or animal… or whatever…) approaching us was someone (or something) we knew and could trust, or if it was a threat to our existence. And so our brains learned to recognize faces and physical attributes as a method of survival. Even today, when any of us see another person, an area of our brain called the fusiform gyrus goes into overdrive. The fusiform gyrus is the part of the brain that categorizes faces, and when we meet strangers this part of our brain searches all of its data to let us know if we should be concerned or at ease. Interestingly, the more the other person looks like us, the more the fusiform gyrus continues its work to classify them. However, if the person looks significantly different from us, the brain activity shifts from the fusiform gyrus to the amygdala – the “fight or flight” center of our brain.

While it’s true that no child is born a racist, the sad truth is that all children can be turned racist almost effortlessly. Because a young child is constantly registering everything as a threat and learns only to classify things as “safe” through a very-brief lifetime of experiences. Since most infants and toddlers spend most of their time around their own family, this natural evolutionary trait quickly imprints a bias against things that are different: different races, different sizes, different smells or sounds. And the stronger that imprint gets, the more the brain starts to shift away from its own “flight or flight” region and moves to the insula – the part of the brain that feels revulsion and disgust. Indeed, people can become so isolated from others who look differently that their brains register these people the same way we register disease or rot. In those cases, it’s not merely “fight or flight”. Revulsion and disgust tell us that something is very threatening to our existence, and we need to get rid of it. And so we cut out the festering wound. We don’t leave rotting food in the fridge. We kill the vermin in our walls. And to some people, they feel genuinely compelled to do everything in their power to destroy someone who doesn’t look like they do.

So the story of Clifford, the Big Red Dog is really a story of our own evolutionary biases against anyone and everyone who looks different than us. Clifford is not just a big dog; he is unrecognizably huge. He is unlike any dog that has ever existed. He should be a dog that strikes terror into the hearts of everyone who sees him, but in the stories, these encounters are limited. He’s also a dog that has caused – and regularly continues to cause – physical and economic harm to Emily Elizabeth’s family. Clifford grew so large, they had to leave New York City (after being evicted!) and relocate to the fictitious Birdwell Island. And while Clifford wants to do good all the time, his size sometimes causes unexpected results that upset people. Mostly, Clifford’s existence is just a desire to be accepted by everyone. He is almost always met with resistance because he is different, and nobody on Birdwell Island can imagine how he could possibly join in for a normal function. The lack of sympathy then pushes Clifford to search for an alternate solution, which always seems to work for everyone, in the end.

And yet nobody tries to destroy Clifford.

Nobody hates Clifford for being different.

Nobody justifies their own biases against this totally unique creature – despite being totally justified (from an evolutionary perspective, at least).

In fact, the very root of Clifford’s massive growth was the fact that he was loved so much by Emily Elizabeth and her family, a behavior the direct opposite of everything we know about brain function, bias, and community.

Now, I’m not trying to equate the taunts I received for being big with the kind of hostility people of color, women, or people with disabilities experience on a regular basis. But even as a child, I recognized something familiar in Clifford’s experience to my own. The constant underestimation of Clifford, the isolation, and the disappointment were all experiences I could share. As a kid, I liked the results of the Clifford stories. The part where the ostracized Clifford saves the day and everyone is thrilled with him. But the actual lesson of those stories is a little more direct, a little less communal. Because over the course of hundreds of stories and hundreds of hours of television (and at least one feature film), we’ve seen that people inherently show their natural bias against Clifford at first. People will bring their own biases to the table, whether they intend to or not. Some of it is merely baked too deeply in our brain’s hard-wired survival system to override it. And it would be glib to say that we should “just ignore” people who would deny us our own humanity. Nothing in human history has ever managed to do that successfully… including the fictional Clifford, who regularly spends a portion of most stories feeling sad and isolated.

If there’s a lesson for me in Clifford, the Big Red Dog, it’s that we should continue to weather the storm in support of our authentic voice. Even more so if that voice flies in the face of society’s standards. Because the bastards aren’t going anywhere. Because you won’t win them over with a single knock-out punch of our own awesomeness. Because all of us are hard-wired to bristle at differences, and if we happen to be a big giant difference – physically, spiritually, creatively, philosophically, politically – we will be met with resistance. The goal in that situation shouldn’t be to “win them over”; it should be to “not lose the faith in ourselves”. Because they may be cheering for you today, but tomorrow they’ll be racking their brains trying to understand you.

Let them do that work. It’s the literal work of being human, and everyone deserves the space and dignity to go through it with patience and compassion.

But that’s all the credence other people’s reactions deserve. They don’t deserve enough power to stop you or to make you feel bad about yourself. And so while they comb the volatile regions of their brains to figure out just who (or what) the hell you are, keep moving through your life the only way you know how – as big as a god-damned house, and as bright as the midday sun.