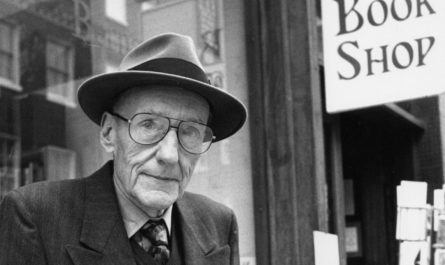

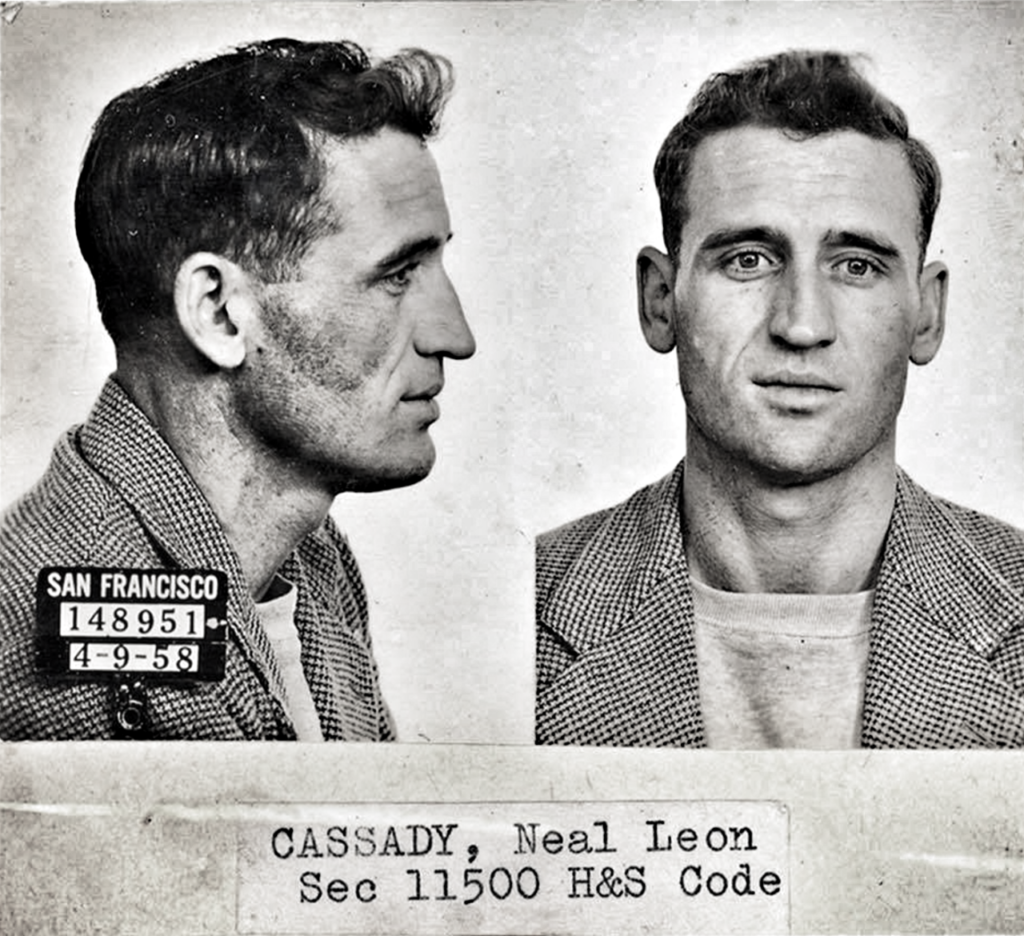

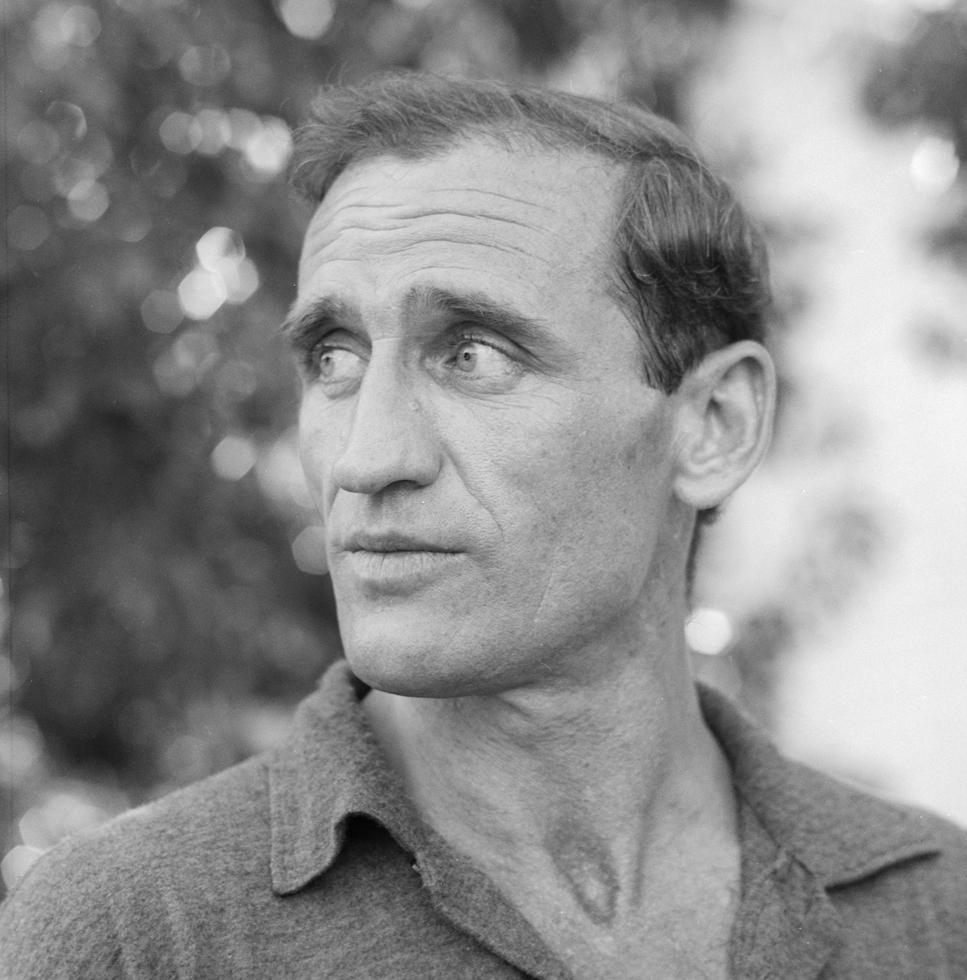

NEAL CASSADY: February 8, 1926 – February 4, 1968

When I re-started this project a few weeks ago, I wrote about Janis Joplin and how she used her “outsider” status to forge a new kind of creative reality. One of the themes from Janis’ life which I didn’t explore too deeply was the power of her live performances. In one memorable review of her live performances, a critic explained how Janis’s live performances had caused her to re-think her policy on clapping for encores. Janis had returned to the stage, encore after encore, with each return performance more heightened and intense than the last. The critic described the experience as feeling like a vampire, just taking and taking from this woman who just kept giving more and more. It was one of the most unintentionally apt descriptions I’ve ever read.

Because vampires feed off the human body, but they never think to ask their meat how IT feels about the exchange. What Janis likely felt as a connection and communication, the critic could only see from one side – a relationship of perpetual one-sided consumption. (I could go for months on my thoughts on the difference between criticism and creativity, but I don’t have to… you’re already reading this.) The truth is, some people are just better suited to communicate through song or written word (or painting or dance or comedy or or or…). We may be able to eloquently share our feelings through creative endeavors, but in person, we’re tongue-tied and pained. Janis was likely one of those people, and ignoring that intent behind those creative efforts effectively stifles an artist’s ability to communicate and connect.

That’s the tricky balance for many artists, particularly those who rely on their art to indirectly communicate and connect with others. The responsibility for allowing and maintaining the connection falls on the audience, and the audience can turn that relationship carnivorous in an instant. Somewhere between the second and third encore, Janis went from “comrade” to “meat” in that critic’s eyes, solely by repeatedly reaching out to connect. But at least Janis was able to showcase her talents. Some artists are so good at becoming “meat” in the artistic exchange, they are remembered as much (if not more) for their sacrifice as for their art. Rimbaud. Early-career Iggy Pop. Basquiat. Sid Vicious. But probably nobody was more representative of that relationship than Beat Generation muse Neal Cassady.

Like most people, I discovered Neal Cassady in Dean Moriarty – the drifter hero-muse of Jack Kerouac’s On The Road. I read Kerouac’s most famous work when I had my first inklings that I wanted to write. I had immediately flunked out of college and decided that the skills I was using to steal and to bullshit my way through life could be used for a higher purpose. The early description of Dean Moriarty resonated with me:

“He was simply a youth tremendously excited with life, and though he was a con-man, he was only conniving because he wanted so much to live and to get involved with people who would otherwise pay no attention to him.”

Jack Kerouac, On the Road

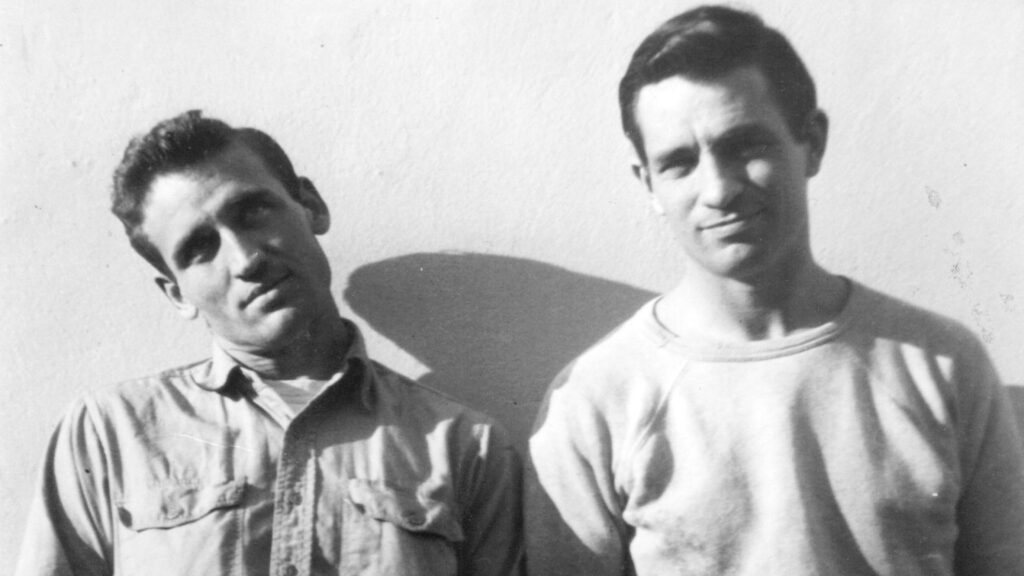

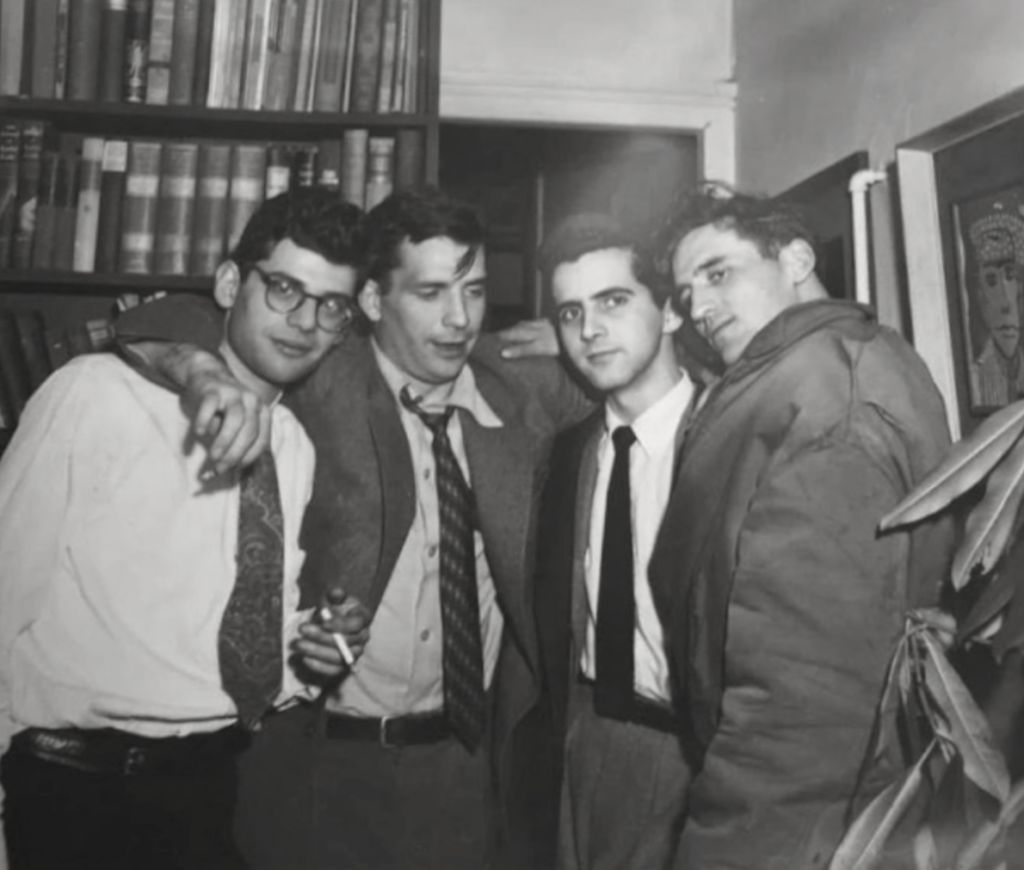

I would quickly learn that On The Road was autobiographical and that Dean Moriarty was based on Neal Cassady, and I began to scour Beat Generation literature for Neal Cassady appearances. He was scattered through Kerouac’s bibliography – as Dean Moriarty and Cody Pomeray. He was a character in John Clellon Holmes’s novel Go, often cited as the birthplace of the term “beat generation”. He appeared as characters in Allen Ginsberg poems and Ken Kesey stories. Neal, himself, was even characterized as a muse in songs by Tom Waits, The Grateful Dead, and The Doobie Brothers. Neal made appearances as “the most fearless person in a world of fearless people” in works of epic journalism: Hunter Thompson’s Hells Angels and Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. He was the inspiration behind R.P. McMurphy in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. I read everything I could find about Neal Cassady. I watched every documentary that mentioned him. I hung his picture on my wall. Neal Cassady seemed to be everywhere in Beat literature, except in the bylines.

For his part, Cassady’s creative output was fairly minimal. He provided the story behind Kerouac’s poem (and short film) “Pull My Daisy”. He wrote an autobiographical novel, The First Third, about his early youth; it was not published until three years after his death. His letters to Allen Ginsberg were collected into a book. And prior to 2014, only clips were available of the infamous “Joan Anderson letter”, an 18-page letter to Jack Kerouac that was purported to be so inspiring, it launched Kerouac’s stream-of-consciousness writing style and gave birth to the physical “on-the-road seeker” ethos of the entire Beat Generation. By all accounts, Cassady packed about ten lifetimes into his 41 years of living, and while he left a legend in his wake, he neglected to leave much of his own art. Which is typical of this kind of carnivorous creative relationship – Neal Cassady’s life was the cow we never consider when remembering the greatest steak we ever ate. And this is a shame because, on one hand, we received something memorably amazing. And on the other hand, Neal Cassady’s life was – arguably – kind of shitty.

Make no mistakes, decades-long friendships with some of the greatest creative minds of American history is pretty amazing. And Neal’s propensity for regularly finding himself at the epicenter of historical counter-culture events in the 1950s and 1960s indicates a non-expendable “plugged in” quality that most of us envy. But these seem to be the results of Neal’s life, a place where he was always trying to “get to”, as opposed to a place where he belonged.

Growing up on the skid row sections of Denver, Colorado with only an absent, alcoholic father (his mother passed when he was 10), Cassady spent most of his youth in reform schools and jails for theft. He regularly stole cars and shoplifted to feed himself while his father was gone for long periods on benders. When his father was around, they spent time together in the kind of bars that held no majesty or allure for young Neal. These were the kind of bars that housed only the most beaten-down souls, and Neal could find no redemption in their well-worn paths. Skid row has sucked all the life out of these hollow men and had imbued Neal with a desire to find a place filled with life and passion, energy, and exploration. It also helped that Neal was most likely a genius, despite lacking any real formal education. His own autodidacticism not only bought him a working knowledge of art and philosophy, but it also made him a better thief, hustler, and ladies’ man. By the time he was a teenager, excitable Neal would regularly steal cars, seduce a young woman, and drive cross-country with her (a widely-prosecuted felony at that time) to meet new people and see new things.

It was on one of these trips to New York that Neal and his new 16-year old bride met friends-of-a-friend Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg. This trip would lead to Neal’s life as muse – and “holy goof” – of the Beat Generation. But Neal’s initial attraction to the pair (aside from a boundary-pushing sexual attraction that they would also indulge) was a desire to learn how to write. Neal asked Kerouac to teach him how to write fiction, and Ginsberg to teach him to write poetry. Both worked with him and shared thoughts on what to read and how to write, but Cassady’s output never seemed to materialize the way theirs did. Perhaps it was just a matter of “having enough time”, as Kerouac and Ginsberg were students and then professional writers, while Cassady worked factory and locomotive jobs. Most of the Beat writers were either single or in fairly open relationships; Cassady bounced from one wife to the next (including at least one known period of bigamy) and having children with wives and girlfriends along the way. While this kind of a lifestyle may stifle creativity, I think it may have been more “symptom” than “disease”. Neal’s problem wasn’t that he couldn’t explicate his thoughts because of his hectic, responsibility-laden lifestyle; I think he may have created a hectic, responsibility-laden lifestyle to avoid having to explicate his thoughts.

The benefit of always seeking something new is that it forces you to never look at where you’ve been. For a child of neglect like Neal Cassady, that’s an enticing proposition. Ever seeking the next amazing thing, he learned from the smartest, inspired the greatest, hung out with the most enjoyable, and bounced through life with passion and joy. And the audience to his life consumed and consumed. But unlike Janis Joplin, who died at 27, eventually, the constant consumption begins to take a toll. When connection and communication are turned into consumption, the artist is effectively told how unimportant they are – only the action remains. And so Neal found himself at 34, a bigamist ex-con recently both paroled and divorced, with five children who wanted little to do with him and literary genius friends scattered around the globe, all heading down wildly-divergent philosophical paths. And Neal had no better handle on reconciling his past than he did a decade before as he barreled cross-country to meet his new fate.

And so he pushed himself further.

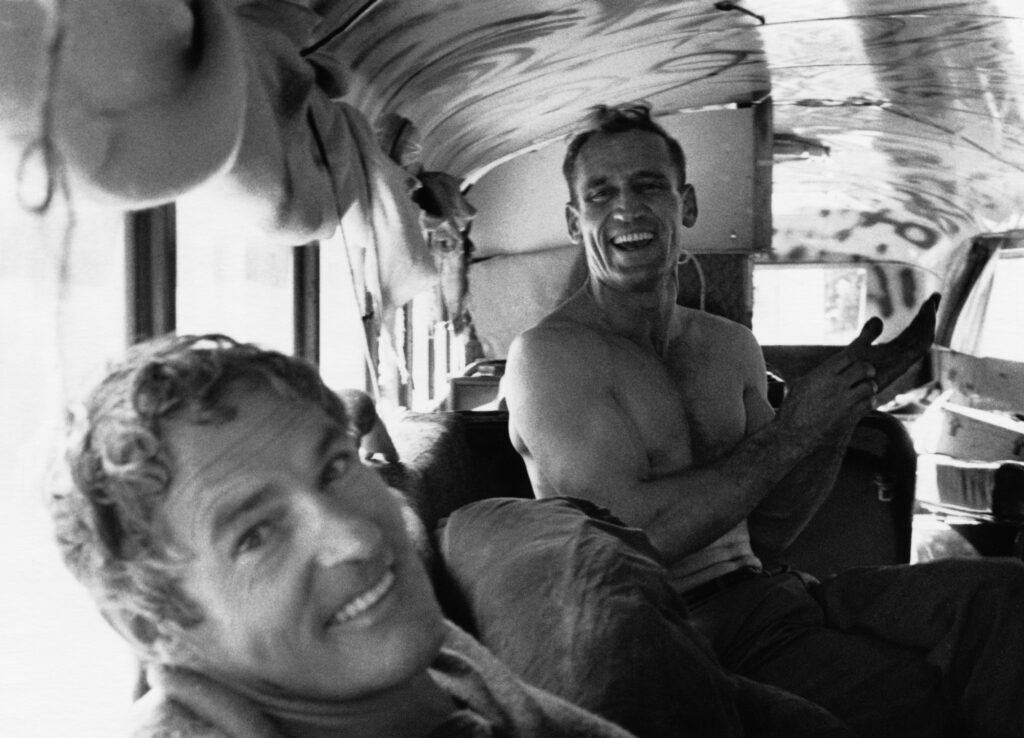

In seven years he would be dead. Frozen to death while walking alongside train tracks in central Mexico while high on phenobarbital. Until the bitter end, he had been driving Ken Kesey’s bus “Furthur” and leading the Merry Pranksters on the ever-present “next adventure”. Never looking back. Never delivering on his own talent.

Because if the sparse works of Neal Cassady teach us anything, it’s that the man had genuine literary talent. He had the ability to tell a compelling and inspiring story. And his life was filled with them. That he only managed to finish detailing the first third (which was, sadly, closer to the first half of a dramatically shortened life) without any attempt to understand how those traumatic experiences shaped him and affected him is telling. Kerouac frequently described Cassady’s life as being the inspiration for his writing style; he referred to it often as “a mad exuberance”. But when Cassady wrote the jacket blurb for the book a few days before he died, he described himself this way: “Seldom has there been a story of a man so balled up.” What Kerouac saw as exuberance, Cassady experienced as anxiety.

What the diner tastes as succulence, the cow experiences as butchery.

As the damsel bleeds from the throat, the vampire experiences life.

And this is not to blame Kerouac. Or the diner. Or the vampire. The receiver has every right to take part in the conversation in the way they see fit, and if they choose to marginalize the sender of the message, so be it. It is the artist’s responsibility to free themselves from the constraints of that; to rid themselves of the need to be consumed and focus only on continuing the conversation within those still connecting. A sender like Janis Joplin never let it affect her. She continued to give more and more with each encore, even when the critic had stopped the conversation. (Who’s to say that she might not eventually have become worn down and changed, had she lived longer? My guess is she wouldn’t have, and would have followed more in the footsteps of Eric Burdon or Leon Russell; but we’ll never truly know.) Neal Cassady, on the other hand, embraced his role as muse/meat do his own detriment. And eventually, to his own dissolution. The role afforded him most of what he wanted in life without requiring him to do the kind of reflection that leads to great art. (Even shitty reflection like Kerouac’s, which mostly just glanced at the surfaces of his own personal issues, still yielded some works of impressive depth.)

Neal Cassady definitely had it within him. But something compelled him to be the sacrifice, not the beneficiary. And while we vampires may be the better for it, the art we love is dirty with his blood.