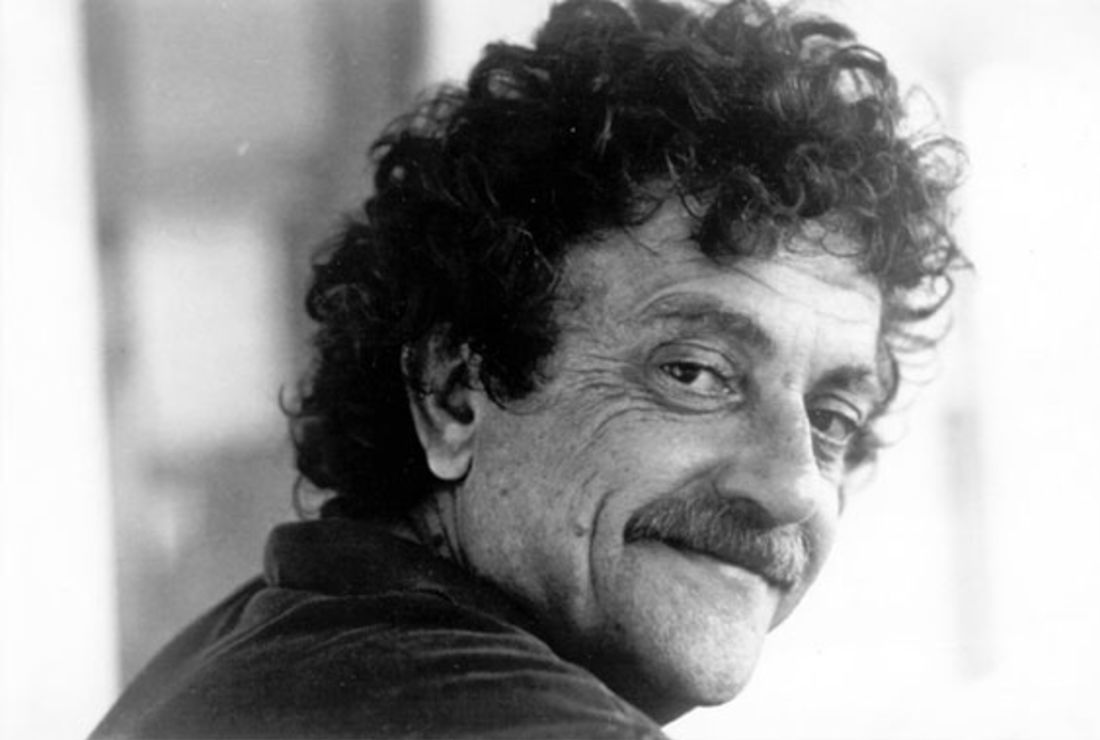

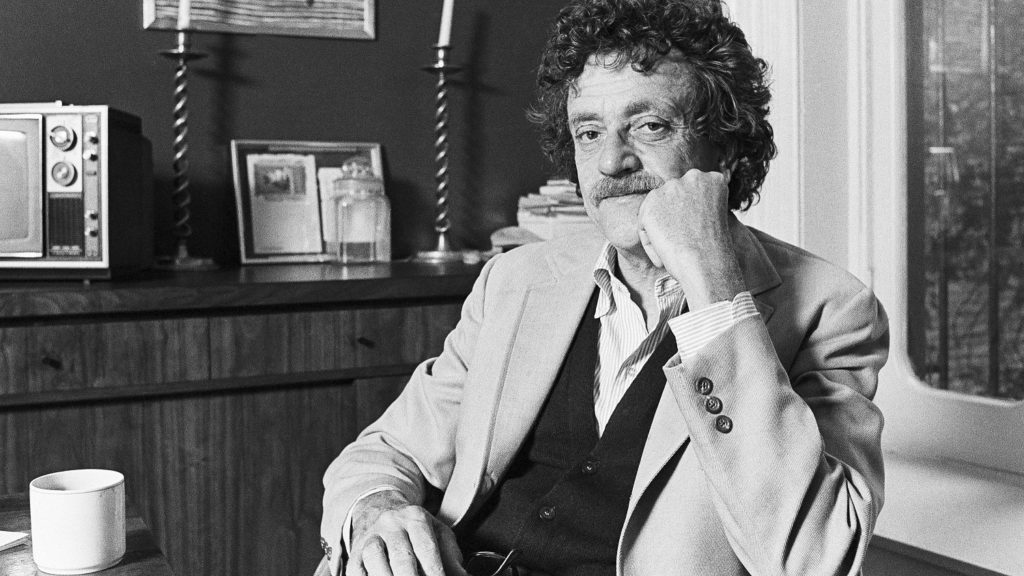

KURT VONNEGUT, JR.: Survived the bombing of Dresden, February 13-15, 1945

“Here we are trapped in the amber of the moment.

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

There is no why.“

I found the writing of Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. in a surprisingly “Vonnegut”-ian way. I was a senior in high school, and I had been kicked out of my AP English class for not reading the homework assignments often enough. The English class I had been relegated to was taught by a teacher who disliked me, and I spent a majority of the time making joking commentaries until she would throw me out of class. I would then go to the room next door, which was in the same classroom that the AP English class was held earlier in the day. That class was led by a teacher who did like me, and her only rule for me being in the class was that I would have to make her laugh to be allowed in, and then I would have to sit on the three-foot high bookshelf in the back of the room (all the desks were filled) where the AP English books were stored and add running joke commentary to her lessons. Since I wasn’t a student in the class, I wasn’t reading any of the homework, and I would regularly get bored. I began taking copies of the AP English books and Ieaving school in the middle of the day, finding a park somewhere and sitting and reading the afternoon away. In short, I was missing school so I could read the books I had been thrown out of school for not reading, which I took from a class that required me to be silly since I had been thrown from a class for being silly. All of us were carving out what we wanted against a set of conflicting rules and preferences that seemed designed to keep all of us from getting what we needed. At the time, those afternoons were some of the best moments of the school year. I had been removed from one class, thrown out of another, and serving in the role of jester in a third class. I was both a failure and a joke, and so the moments on park benches reading the books felt creative and curious. One of the books I remembered taking with me was Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five. The book didn’t make much sense to me at the time, and without a teacher to explain some of the novel’s context to me, it felt too abstract to truly understand. All I knew was that the novel’s main character, Billy Pilgrim, had survived the bombing of Dresden during World War II; it was years before I knew the same had happened to Vonnegut.

When Kurt Vonnegut was a prisoner of war in a Dresden labor camp during World War II, both the Germans and the American POWs both assumed that they would be safe from American bombing raids. After all, Dresden was the capital of the German Saxony province, and it had a rich history of the art and architecture of Germany. Even then, twenty-two-year old Vonnegut understood the contradiction; humans were expendable, but the art that represented those people was not. And so it was seen as a shocking horror when Allied forces began firebombing Dresden in February of 1945. The prisoners in Vonnegut’s labor camp were shuttled to an underground series of slaughterhouses, where they were safe from the fire above. Vonnegut was housed in Slaughterhouse Five. When the bombing ended, he and his fellow prisoners were used to locate, stack, and dispose of the charred remains of Dresden civilians. Vonnegut eventually escaped from Dresden and after the war, he began writing. He wrote Slaughterhouse Five in 1969, and it was Vonnegut’s attempt to make sense of what happened in Dresden, even though the point of the book was that no book could ever explain the illogic of war. The text itself acknowledged the futility of writing that kind of a text. But Vonnegut was writing for a higher purpose. As he would later say:

“I think the message of any strong book—good book–to a reader is, ‘You are not alone. Other people feel as you do.’ And there are a lot of lonely people out there who are not nourished by popular entertainment, or the advice of their stupid parents, or whatever. So I hope good books let young people figure things out for themselves, and to know, ‘Hey, I’ve got a friend somewhere else.’”

Unlike existential philosophy, which would advocate that people choose how they react to these horrible events, Slaughterhouse Five took a more “escapist” approach. In the novel, the protagonist Billy Pilgrim became unstuck in time, and would regularly travel to better times and places in order to escape the contradictions and misery of the current moment. Instead of trying to find a positive spin on something problematic, Vonnegut simply drafted a catchphrase that was as much supplication as acceptance: “And so it goes.” No fight, no wish for a better future, no complaints, no worry… just “And so it goes.” The phrase would appear more than 100 times in the novel notably after scenes like these:

”Weary’s father once gave Weary’s mother a Spanish thumbscrew in working condition—for a kitchen paperweight. Another time he gave her a table lamp whose base was a model one foot high of the famous “Iron Maiden of Nuremberg.” The real Iron Maiden was a medieval torture instrument, a sort of boiler which was shaped like a woman on the outside—and lined with spikes. The front of the woman was composed of two hinged doors. The idea was to put a criminal inside and then close the doors slowly. There were two special spikes where his eyes would be. There was a drain in the bottom to let out all the blood.

And so it goes.”

But Vonnegut’s wish wasn’t that we would accept the horrors and absurdities of life and live among them. In the book, Billy Pilgrim traveled throughout his life – crossing time and space in a second, going forward and back in an instant. Vonnegut’s point was more positive, and lauded the bountiful nature of existence. If there’s an absurdity in this area of your life, he seemed to say, acknowledge it and let it be. Then turn away and go to another area of your life that is more positive. The horrors and absurdities of life are a part of our life, but we needn’t dwell among them forever.

Slaughterhouse Five helped Vonnegut exorcise a number of demons he was left with after the bombing of Dresden. But it was a story that spoke to everyone. We don’t need to experience the horrors of war to understand it. Our lives are riddled with absurdity and pain. Often, the source of that absurdity and pain is something larger than us: a government, a religion, a system, a popular belief. And when we face a well-crafted system composed of many people and a lot of brain power, it’s easy to feel like we’re the problem. Most people spend their lives trying to fit themselves into systems larger than themselves. Sometimes that fit is natural, but far too often we spend our time trying to re-arrange our lives and our beliefs and our perceptions of self to fit into the occasional senselessness of those systems. Vonnegut understood the gaping sense of “outsider-ness” that those moments left, and in one of the book’s seminal moments, Billy Pilgrim lies beside his wife on their wedding night. She says that she thinks Billy has a lot of secrets that he doesn’t share. Billy, able to see the entirety of their relationship, realizes that it will have ups and downs, but mostly it will be tolerable. And he thinks about an epitaph he had seen on a gravestone that said, “Everything was beautiful, and nothing hurt.” Billy’s wife recognizes the scars left over from the war, and she wants to understand the things – like the bombing of Dresden – which caused them. Billy, on the other hand, plans to remain unstuck. He knows he will turn from things that he can’t change (“and so it goes”) and move to the part of his life that is happier and more valuable. As we all should. Accept the things that have scarred us, but learn to put our energies into the areas of our lives that are healthy. If we bring the emotional baggage from the terrible moments into the better areas, we haven’t become “unstuck”. Our lives are a series of moments, and it’s easy to get stuck in a moment. To let it become who we are. But the goal is to move to a better area of our life. Whether it’s leaving behind a failure in high school or the bombing of Dresden, “and so it goes”… we just don’t need to stay with it.