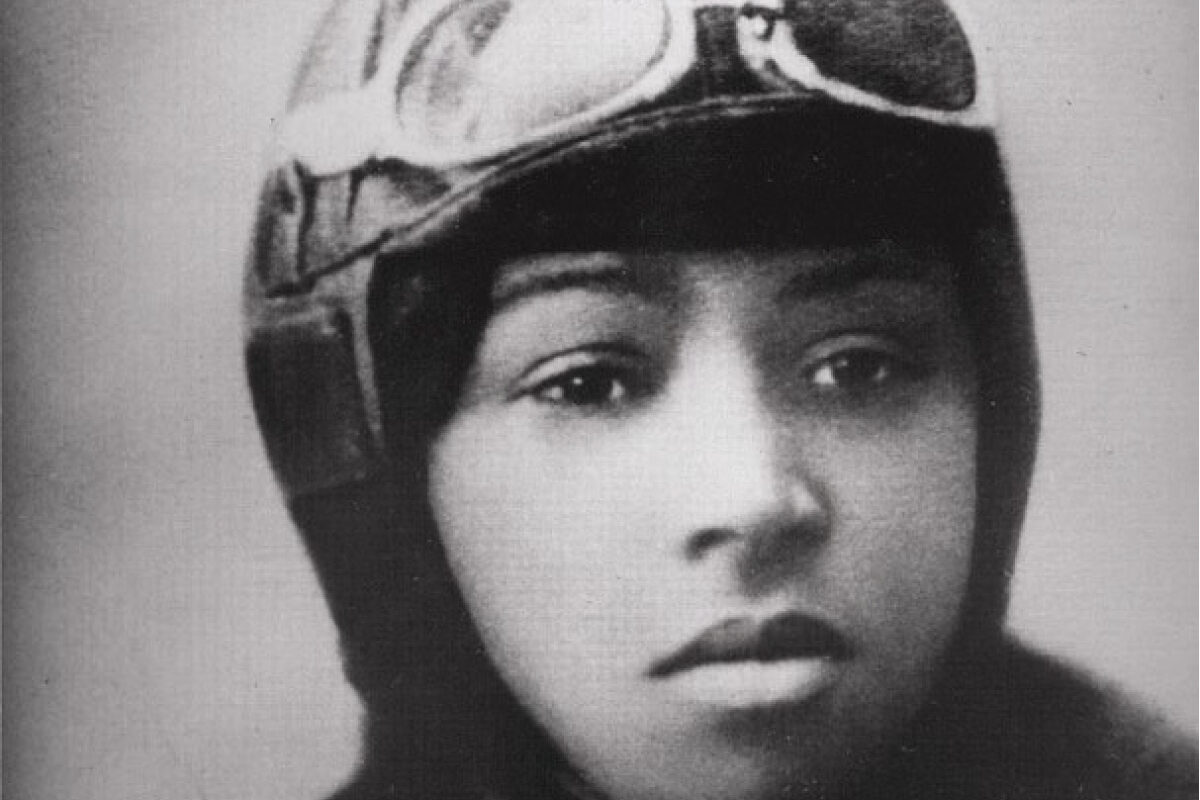

BESSIE COLEMAN: January 26, 1892 – April 30, 1926

In recent weeks, I have grown increasingly horrified by the political divisions in America. It’s not that “there are two realities”; that has always been the case, to one extent or another. It’s not the amoral “I was appalled when you did this yesterday, but I’m fine with me doing it today” flip-flopping. It’s not even the total assault on logic or consistent thinking (which is my personal pet peeve). What frightens me most is the terror and hopelessness that all of these problems – aggressively fueled by internet algorithms – have created.

At first, the videos made me laugh. I chuckled at Trump supporters weeping hysterically over instantly-debunkable claims (“Biden has outlawed the American flag!”). One man claimed he was now a powerless slave “to the dictatorship” – via a viral TikTok filmed at a Denny’s. I shook my head and chuckled. But as those sentiments grew and as the constant barrage of fear-based comments compounded, I realized that many of these were not just social media clickbait; people were genuinely terrified. The “if it bleeds, it leads” nature of media – traditional and social – appears to have finally moved people in this country (and likely the rest of the world) into a state of learned helplessness.

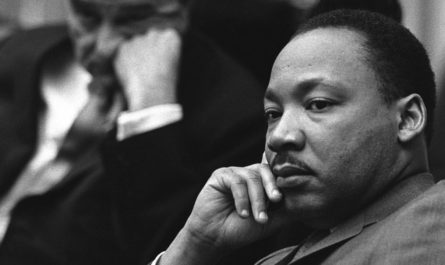

Learned helplessness is a behavioral state where people (or animals) accept a state of powerlessness and stop any attempts to make things better. It is a state achieved after repeated negative stimuli. In the late 1960s, psychologist Martin Seligman did the earliest research on this state with puppies. He would place puppies in a high-walled box and apply electric shocks through the floor; all the puppies would frantically look for ways to make the shocks stop. Some could leap over a small partition in the middle of the box to an uncharged area of floor. Some could press a lever to make the shocks stop. But some had no options. They were forced to withstand the pain until it ended at some random interval. Unsurprisingly, the puppies who could end the suffering learned quickly to take action and to try different ways to make the shocks stop. The puppies in the helpless group, on the other hand, eventually gave up and laid down and whined until the shocks subsided. On subsequent experiments, these same puppies would be put in boxes filled with options to stop the shocks: easily-cleared partitions, obvious levers that would stop the charge. But none even tried. Researchers would pick the helpless puppies up and move them across the partition to safety. They would guide their paws to the levers and stop the shocks. They trained the puppies repeatedly to protect themselves. But the damage was already done. As soon as the shocks began, the puppies would lay down and whine and wait for it all to be over – completely helpless.

That’s where we have been for years, as a society. I know; it’s where I have been for years. And maybe I avoided making ridiculous claims on social media, but in recent years I have known those helpless feelings all too well. Like everyone, I have been inundated with constant negative stimuli to the point that it felt hopeless to fight. Part of what made me revisit this project was a search for balance: a series of positive influences to balance out the constant negative messaging. And so I began to revisit my gratitude for people who typified behaviors I hoped to model. And few people exemplify the battle against learned hopelessness like aviator Bessie Coleman.

When I was younger, they changed the name of one of the main roads encircling Chicago’s O’Hare Airport to “Bessie Coleman Drive”. There was no fanfare or public explanation that I knew of, just new signs along the expressway exit ramps. It was years before I learned about one of Chicago’s most exemplary citizens. (She was brought to my attention by fellow Chicago aeronautics pioneer Dr. Mae Jemison, the first female African-American astronaut.) By all accounts, Bessie Coleman should have been someone who learned helplessness. She certainly would have been forgiven for it, if she had. Tales of Bessie Coleman claim that she was driven by sibling rivalry or a fierce desire for justice. Whatever it was, Bessie Coleman did not learn to be helpless, despite a lifetime of plausible reasons for it.

Bessie Coleman was born in Texas in 1892, the tenth child of sharecropper parents. Bessie’s father was Cherokee and her mother was African-American. By the time she was 9, four of her 12 siblings had died and her father decided to return to Indian Territory (soon to be renamed “Oklahoma” when it earned statehood) and look for better work. Her mother decided to remain in Texas for the children’s education, and the marriage dissolved. The children pitched in to help, but the hardscrabble existence of sharecropping was made exponentially more difficult and dangerous without a man as the head of the household. Bessie was an exemplary student, and her mother sent Bessie off to college after high school, but the tuition money ran out after one semester. Instead of returning home in defeat, Bessie moved to Chicago to live with two of her brothers and work as a manicurist.

In Chicago, she heard tales of France from her brother and from customers returning home from WWI. Tales of self-determined women who did things unimaginable in America at the time. Black women who owned and drove cars. Who owned and drove businesses in integrated areas. Even black women pilots!

Bessie, a strong math student, became fixated on the idea of women pilots. She decided that she wanted to learn to fly, but this was 1915. Powered flight was barely a decade old, and licensed flying was even more recent. Almost no women were licensed to fly at this time, and absolutely no black women could earn a license in America.

These are the moments where learned helplessness would normally take effect. A dream is deterred at every corner. Bessie Coleman had limited formal education, and no hope to continue it further. She was legally prohibited from earning a pilot’s license everywhere in the country. And if she somehow miraculously did earn that license, she couldn’t afford a plane. Nobody would have blamed Bessie Coleman for giving up on that dream and settling into life as a manicurist. It is simply too many negative stimuli for many people to continue. Not Bessie Coleman.

Some have claimed that her brothers’ incessant teasing was what drove Bessie to want a pilot’s license so badly. Her brothers would mock her regularly for being just a manicurist” in a world filled with black women doing extraordinary things. By all accounts, it was quite misogynistic (but typical of the times) and was used to lord their military travels over her gender-constrained homebound state. Others have claimed it was her mother’s early steadfastness in the face of her father’s disappearance. Some say it was exposure to the growing black cultural movements in Chicago at the time. Still, others say it was merely a vivid imagination and an uncompromised dream that guided her. In any case, Bessie Coleman was in an all-too-common environment where learned helplessness was almost a guarantee. And yet, she continued pushing back.

Since she could not get licensed to fly anywhere in America, Bessie decided that she would go to France and earn her license. Of course, she couldn’t afford the trip and she spoke no French. She took a Berlitz course in French and told her dreams to everyone. Soon, her struggle earned the attention of Robert Abbott, the publisher of Chicago’s African-American newspaper, The Chicago Defender. Abbott wrote an article about her, and soon her trip was funded by generous patrons. Bessie moved to war-ravaged France in 1820, and within a year, she had earned her pilot’s license but remained in Europe to study under French wartime aces who understood how to pilot even the least-agile planes in graceful and dynamic ways. She even met with Dutch aircraft designer Anthony Fokker to learn how advanced aircraft were being designed and built.

By the time Bessie returned to America, she was prepared to make a living as a barnstormer, which was the only possible aviation job available to an African-American woman.

Bessie used her uniqueness to fuel her desires for equality. She once said:

The air is the only place free from prejudices. I knew we had no aviators, neither men nor women, and I knew the Race needed to be represented along this most important line, so I thought it my duty to risk my life to learn aviation…

Bessie continually used her role as a sole representative to project a positive influence for other African-Americans. She was approached to perform and appear in a movie for black audiences. When she arrived at the set, she found that her costume was a “barefoot in dirty rags” caricature of a black woman as uneducated and unclean, and uninspired. (It’s a caricature that reeks of learned helplessness, by the way.) Despite how much the appearance would have personally helped her, Bessie walked away from the project. She felt it would be too damaging for black people to see. Instead, she put her time into air shows and giving rousing motivational speeches. She refused to participate in airshows that denied entrance to African-Americans, and her popularity was so high, most airshows couldn’t afford to exclude her. Her biggest dream was to inspire, motivate, and elevate African-Americans, and she knew the best way she could give back to her community was to open a flight school for African-American pilots. She quickly set to work saving money for what would be her crowning achievement.

There is no poetry or mythos in Bessie Coleman’s unfortunate death at the age of 34. Powered flight was barely 20 years old, at that point. Bessie’s death was neither her fault nor useful as a lesson. Aviation was a new technology, and planes crashed frequently, often for ridiculous reasons. In Bessie’s case, she had purchased a poorly-maintained plane in Texas and planned on flying it home with her mechanic. Since the lane would be used in barnstorming shows, Bessie needed to climb out of the plane to examine it mid-flight, the way the wingwalkers and parachutists would, so she did not buckle herself into the passenger seat. Minutes into the flight, a loose wrench left in the engine compartment jammed itself into the engine and seized the entire plane. The plane went into a spinning dive and Bessie was thrown from the plane and fell 2000 feet to her death. The mechanic tried everything to save the airplane and himself, but the crash was too violent. Bessie would be buried in Lincoln Cemetery in Chicago, where many of Chicago’s most prominent African-Americans are laid to rest. To this day, the cemetery claims to regularly see small planes fly overhead and drop flowers, almost certainly in honor of Bessie Coleman.

Too often, the lesson shared about Bessie Coleman is “African-Americans can and should do anything white people are allowed to do”, which is a reasonable lesson. But that is a lesson of opportunity; it merely grants people access to capability. But if we reflect on Seligman’s puppies, once helpless is learned, all of the access in the world doesn’t matter. We can have access to licenses and permissions and tools and technologies to make our lives instantly better, and instead, we’ll lay down and wait for the pain to stop inflicting itself upon us. Bessie Coleman realized that it wasn’t enough to just showcase her own escape from helplessness; she had to teach them how to escape. And if they were too learnedly helpless to heed her teachings, she would also work to craft a world where there were fewer shocks. And she would inspire newer, younger, more hopeful generations how to overcome or extinguish those limiting shocks.

That’s the lesson that feels most applicable to me today. (I say that with total awareness of the privilege behind such a statement.) But in a world where, at any time, almost 50% of the population can almost instantly be made to feel totally helpless in the face of negative stimuli, it matters. It matters that we stop adding to the negative stimuli.

It matters that we give ourselves moments of hope. Of self-determination. Or empowerment.

It matters that we stop fighting.

It matters that we support each other, even in the tiniest ways.

It matters that we all give each other just a little room to try to find ourselves again in the midst of helplessness.

We may not all be Bessie Coleman, but it matters that we stop – in any way we can – making the world more helpless.