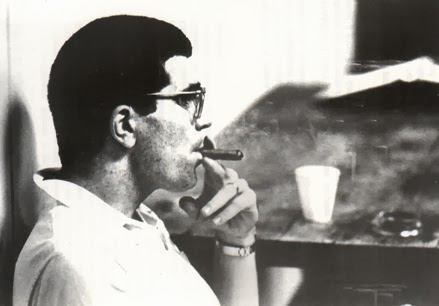

DAVID MAMET: born November 30, 1947

I was 19 when I first discovered the power of American theater. Prior to that, my experience with stage plays had been assigned reading in English classes, and most of that had been Shakespeare, Aristophanes, and “Doctor Faustus” – plays either rich in language or broad in theme, but steeped in enough history to make their study relevant. But none of these were plays that could really stir my teenage passions. It wasn’t until I was in my late teens and spending a drunken weekend in Columbus, Ohio visiting a friend that I discovered American playwrights. We were visiting Long’s, the classic campus bookstore on High Street, when I saw a paperback with Sam Shepard on the cover. I was a fan of Shepard’s acting. He had played my grandpa’s personal hero Chuck Yeager in one of my favorite movies, The Right Stuff. I’d been a fan of his work as the defeated family farmer in Country and as the terrified zealot in Resurrection. But I was unaware he wrote. The book felt so important to me, I paid for it with a bum check and headed back to Illinois the next day. I’d read half the book by the time I got back to Chicago. I spent the following weeks trying to find similar playwrights. A librarian who had been helping me find similar playwrights had been listing off playwrights she thought I might like whom I may not have already read. And then she said, “Well… and Mamet. Right?”

I remember the exchange because her “Right?” was her way of saying, “But you’ve obviously read him already. Is that correct?” The sad fact was, I was a fan of his movie House of Games, but I didn’t really know his name or anything about his plays. What struck me as I began reading Mamet was how difficult his text was to read. Mamet has always been known for his command of language, and it was different enough to me to be intriguing. Characters talked over each other, interrupted each other, finished each others’ sentences. Characters would frequently interject random thoughts into established conversations. Characters would casually refer to people or places or events with the assumption that the other characters (as well as the reader) would know what they were talking about. More than anything, characters would simply drift in and out of conversations, following the narrative within their head more than the narrative they were trying to convey. And then, finally, when given the right set of circumstances, characters would launch into lengthy, detailed monologues that were like verbal fireworks – wondrous displays of verbal activity. And those moments – more than anything in Mamet’s work – show that his characters at “their best” are actually just examples of his characters reaching the highest peaks of bullshit and/or self-delusion.

Much like the librarian who approached me with the idea of reading Mamet with an indirect and insufficient “Right?”, Mamet writes the way humans speak. More accurately, Mamet writes the way humans think. Later in my life, I would study exploitation films and cartoon strips, and one theme would define both of those genres was similar to what helps define Mamet: the immense power beneath what we can’t see. In cartoon strips, when a man wears a hat in panel 1 and the hat is on the ground in panel 2, the reader must fill in the gap with the “how did that happen?” In horror movies, the villain popping out from behind a curtain to a loud orchestral stab is scary, but nowhere near as scary as the moments where the would-be victim slowly wanders through the house in fear. They say that the worst part of torture isn’t the physical punishment; it’s the moments of reprieve in between the torture sessions which are the most damaging. The moment where our mind fills the glaringly-apparent gaps with every manner of hell we can imagine. Mamet’s characters live in those moments.

I’ve always felt a certain kinship with Mamet’s characters’ speech patterns. My life has been a long pattern of awkwardly-blurted asides in an attempt to connect. My life has been plagued with clumsy half-thoughts and tapering-off sentiments in search of a glorious line of bullshit. More specifically, my life has been a life where words feel as much like a safety net as a stick of dynamite, and where I am always its uncomfortable steward. I’ve spent my entire life worrying about words. Wishing I could find the sentences and thoughts that would weave a warm nest beneath me and my conversation partner. Fearing that the wrong combination of words might lead to destruction.

If I’m honest with myself, I can’t remember a time when words didn’t feel terminal. When it didn’t feel like I was ever more than one poorly-combined choice of words away from destroying any important relationship. As a result, words have always carried inordinate power with me, and as I grew older and the stakes in my life grew higher, I found myself using fewer and fewer of them. I found myself “choosing” more words than “experiencing” them. Everything I said became an attempt at appeasement and conciliation; a pre-emptive verbal surrender to ensure that my words could not betray me and end a relationship or a job. And much like in every Mamet play, there’s a moment where the character realizes that words have betrayed him, and the line of magical bullshit that may hide his flaws and his fears for another day can no longer be found, and the old stories have lost all their lustre and the interjections into other conversations no longer feel like “understanding” and now seem like “interruption”. And at that moment, we’re left with nothing but silence. And loneliness. And misunderstanding.

But the fact is, the words aren’t going anywhere. They’re a part of us. And when we find that bottom, and when that silence is all we have, and when the bullshit can’t carry us any further? We need to return to the words. And either reconcile with them or die. There are no other options.