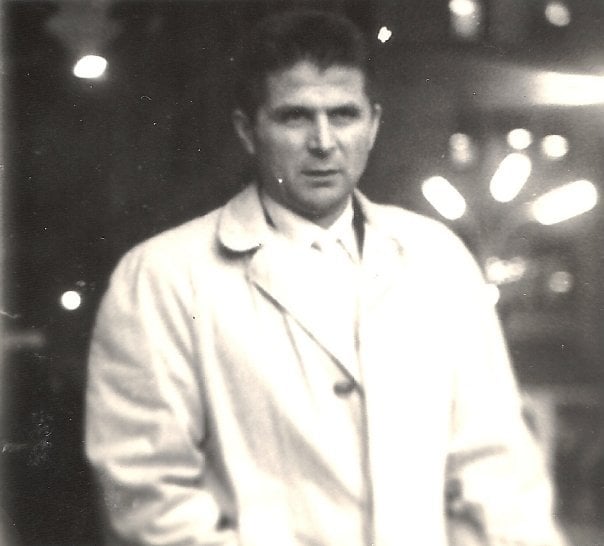

Ivan “Johnnie” Vrbetic: 1922 – October 23, 2009

Chicago is a city with a proud pub tradition. Generations of Chicagoans hold firm to social traditions from their European ancestors and spend their evenings at local bars. It’s not rowdy or sloppy or boisterous, despite Chicago’s “stormy, husky, brawling” reputation. People find a few bars where they feel comfortable and spend their nights hanging out at the bars, enjoying a few drinks and being with friends and regulars whom they grow to know. For years, Chicagoans have boasted that the city has more bars per capita than any city in America (a disputed fact). It’s a boast of community, not debauchery. Chicagoans know that their local bars are symbols of community and comfort, and having one on every block is a sign of a connectedness other cities can’t understand. In my twenties, I discovered a few bars that I would frequent, and one of them became an important part of my life until I finally moved away in 1996. When I would return for visits, I always made sure to return to Johnnie’s Lounge to visit with Ivan “Johnnie” Vrbetic.

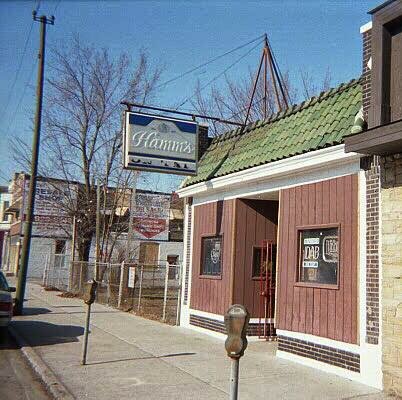

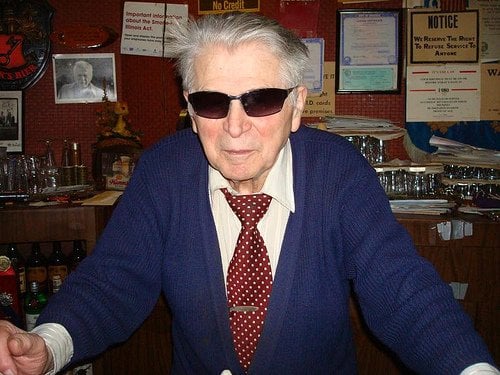

Johnnie Vrbetic was born and raised in Croatia. He survived the chaos of World War II and the Independent State of Croatia, a period he would only describe in the vaguest of terms due to the Axis alignment during the war. After the war ended, Johnnie traveled Europe and finally moved to Chicago. He worked at a tool-and-dye plant until 1969 when he bought the bar at 3425 N. Lincoln in the predominantly Slavic neighborhood of Roscoe Village. Friends and I used to joke that Johnnie decorated the bar in 1969, found the decor to be pleasing, and never felt the need to update it again. By the time I discovered Johnnie’s in the early ‘90s, it appeared to be a relic. The Hamm’s beer sign that hung above the entrance was faded colorless, and only the raised lettering informed what brand it advertised. (Not that it mattered. Johnnie no longer carried Hamm’s, anyway.) Inside, the bar was decorated with ancient promotional beer signs, and stocked with an immense bar of unfamiliar bottles. Bygone era bar promotions (coasters of topless models, branded wall calendars with photos of snowbound Idaho, etc.) were still available, clearly printed up in the 70s and never completely distributed. Johnny kept the bar clean and he was clearly proud of it; he just never sought to “change with the times”. The pool table was slightly tilted and the TV behind the bar relied on an antenna and rabbit ears to get the faintest, static-filled picture. The closest Johnnie came to updating anything was the juke box, which worked on a completely random schedule. If I were to guess, about every five or six years, Johnnie would find a place that sold 45 records, and he would buy a handful and put them in the jukebox with no rhyme or reason. Ray Charles country songs, polka songs, New Kids On The Block, Sinatra, “Happy Birthday To You”, Willie Nelson, Weird Al. None of this is to say that Johnnie’s bar was a mess. Johnnie took huge pride in keeping a clean bar. He even kept himself presentable, always wearing shirtsleeves and a Windsor-knotted tie, always held neatly with a silver tie clip. And despite being in his early 70s when I began frequenting the bar, he would open the bar seven nights a week and run it until closing time at 3am. My friend Michael and I would sit at the bar – often the only two people in the bar, the entire night – and sit and talk. Johnnie would make a little conversation, serve us beers and Rock & Rye, and then go sit at the end of the bar and fluctuate between sleeping and watching TV. He trusted us, and we trusted him. Because once you got into Johnnie’s, you were trustworthy. It was getting in that was the hard part.

In 1988, two young men entered the bar near the end of the night and attacked Johnnie with a baseball bat. He was brutally beaten and robbed – the kind of attack that would make anyone understand if he had decided to sell the bar. After all, Johnny was 66 at the time of the attack. But fear of danger and injury had been driven from Johnnie as a young man. His tireless work ethic also drove him. Still, Johnny recognized the danger of being a septuagenarian barman, and so he installed a lock on the door which could only be opened with a buzzer from behind the bar. “They vant me to leaf,” Johnnie told us one night, recounting the attack, “but I put buzzer on door. Tell them to go **** themself.” And from then on, Johnnie personally inspected everyone who came to the door. He would shuffle slowly out from behind the bar, walk to the door, and peer out the tiny porthole window at the person requesting entrance. Regular patrons knew to be patient; people seeking entrance for the first time often wandered away before Johnnie could even get to the door. The first few times I tried to get in Johnnie’s, he came to the door and saw my 6’6”, 300+ pound frame and simply went back to his barstool. (Eventually, a friend of a friend of a friend got one of my friends in, and we went together the next night. And then for many years, after.)

It’s been about fifteen years since I last saw Johnnie, and five years since he died. And I could continue this meditation with story after story of the good times I had at Johnnie’s. I could talk about the things I learned from Johnnie by the example he set. But Johnnie’s importance to me was more elegant than that. When I started going to Johnnie’s, I was in my early twenties. I was directionless. My closest friend had died as the result of an accident. I was young and angry and very near hopelessness. More than anything, what Johnnie’s provided was a “clean, well-lighted place”, a term taken from an old Hemingway short story. In the story, an elderly blind man sits and drinks in a café late into the night. The two waiters discuss how the man had recently attempted suicide, but survived. The younger waiter is angry at the man, because it is late and the young waiter wants to go home where his young wife waits for him. But the older waiter understands that the elderly blind man has nothing left that matters, and that in the absence of any greater purpose, we sometimes find meaning in the simplest things. In this case, it’s a clean, well-lighted place. That was what Johnnie provided for then handful of people who visited his bar in the 90s. As lost as I was, I could find some peace in the idea of Johnnie’s. It was a place I could go that was always clean and organized. (At one time, Johnny would use a ruler to measure the distance between the ashtrays on the bar.) There was no chaos or drama from other people. There was no chance of a fight or an argument. Any successes we had outside of the bar were received with a supportive lack of enthusiasm. Failures were forgiven and ignored. If I could assign one feeling to being at Johnnie’s, it’s an easy choice: peace. I always felt at peace at Johnnie’s. Inside the clean, well-lighted bar, I could relax and breathe easy and enjoy myself for a brief period. Outside was dark. Outside was my life. And it was anything but peaceful.

I was heartbroken when I heard Johnnie had fallen at work five years ago and broken his neck. Ever the tough-as-nails Croatian, Johnnie hung on for a number of weeks, and then finally passed away. He was 87. It was a gruesome ending for a man who had given me so much peace. Ironically, just a few months before, I had recorded an album with a group of musician friends. The album was a gift for my wife, who had requested that I give myself a break from the daily grind of work and parenthood and spend some time “re-charging” my creative soul with music. I called the album “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” and the cover art was a picture of Johnnie’s.

I have hundreds of stories about Johnnie and his bar. But only one story matters – the one I’m telling now. Because it was Johnnie’s that helped keep me around so that I’m here to tell this story today.

Requiescat in pace, Ivan. I owe you more than you ever knew.