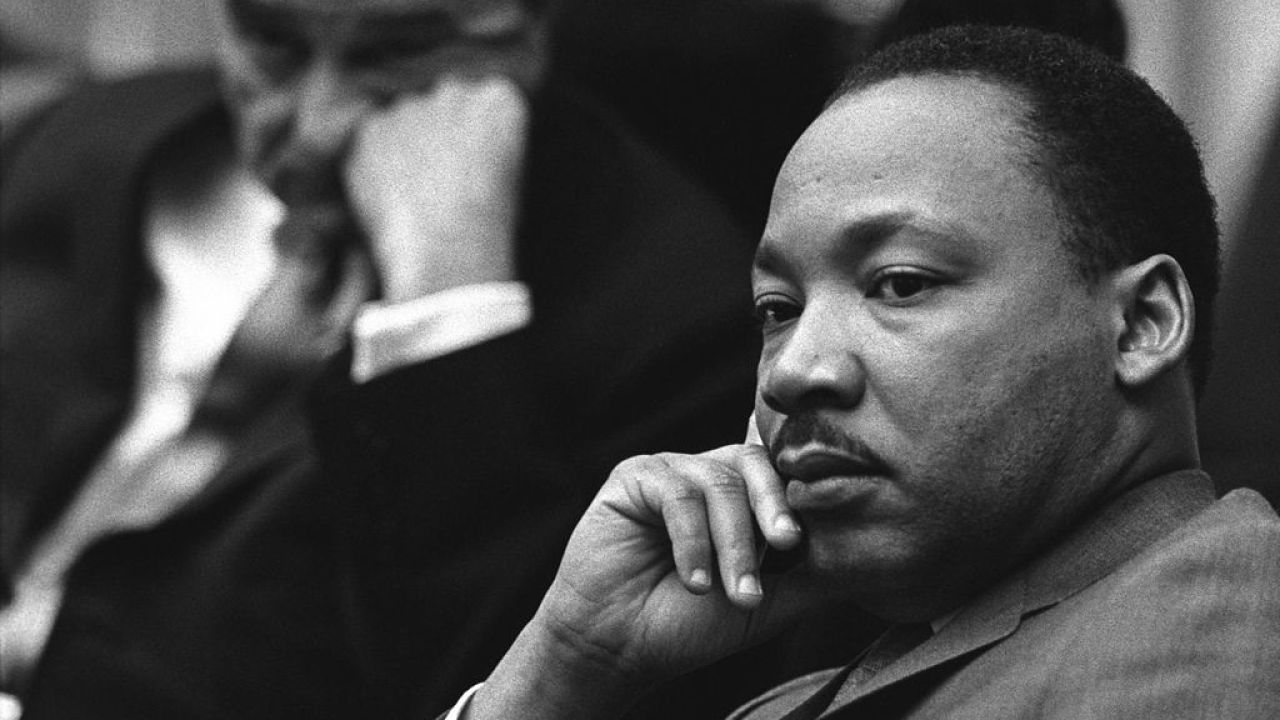

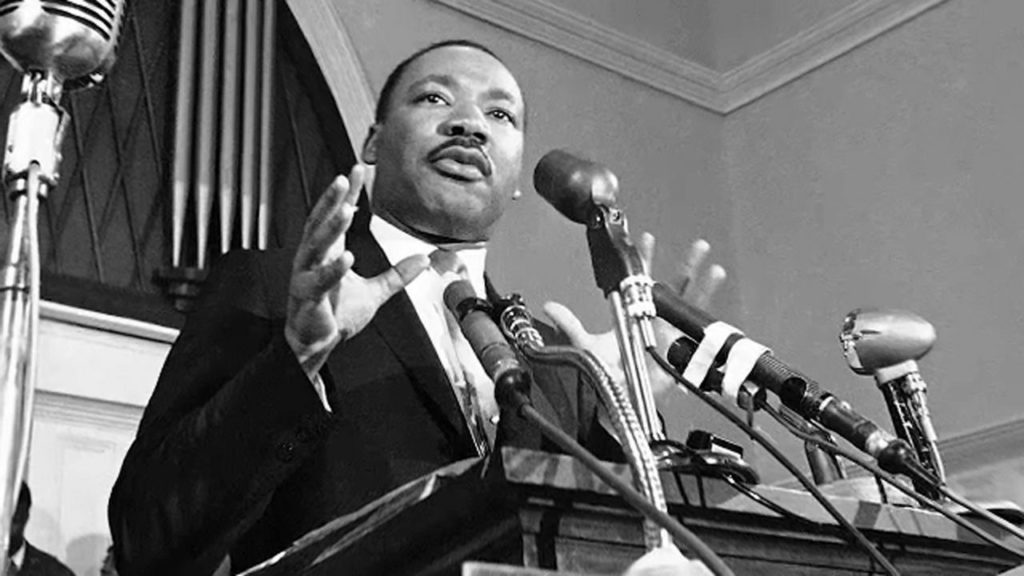

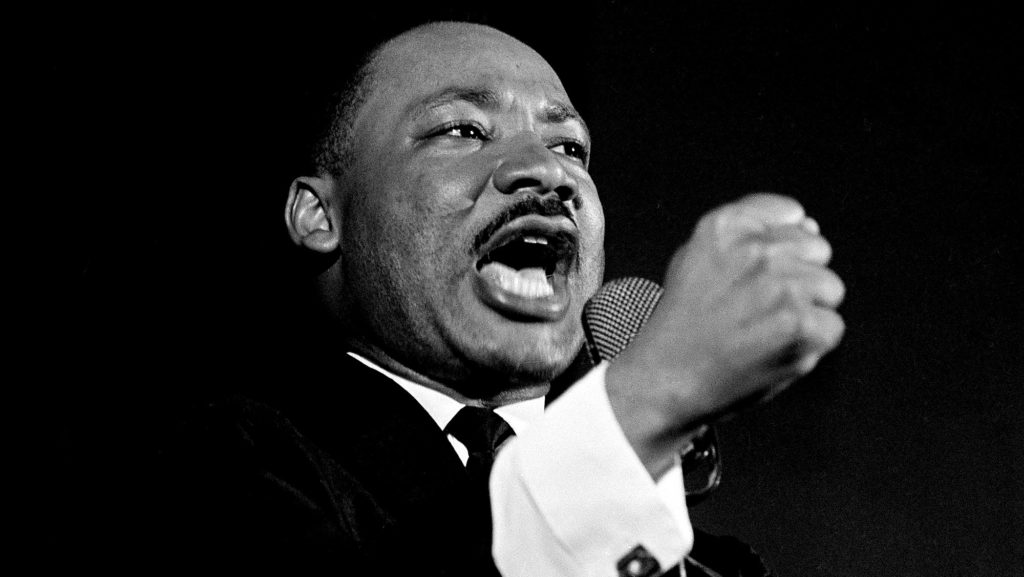

DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR.: January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968

Getting rich is simple; save more money than you spend.

Getting fit is simple; eat less and work out more.

Being happy is simple; just avoid pain and seek out pleasure.

So many things in life can be boiled down to simple formula of inputs and outputs. And it’s true; these formulas are simple, and people blithely wield them as evidence of moral failing or a weak backbone. “Of course you can lose weight,” they say, “it’s simple. Just eat less.” And yet we remain a population overweight, overburdened with debt, supporting huge markets for self-help guidance and prescription anti-depressants. The formulas for wealth and health and happiness are simple; this does not mean that executing these formulas is easy. Because we all bring a lifetime of experience to every moment of every day, a collection of triumphs and traumas and scars and glories. Confidences and fears. Certainty and doubt. And depending on our state of mind, no amount of simplification can make a formula easy enough to complete, or no hurdle is high enough to stop us. My wife and I often discuss why I allow certain people to walk all over me during personal or business interactions. After all, the formula is simple: when being bullied or disregarded, simply standing up for your rights and your boundaries will almost always stop the process. And yet I never seem to. Because as simple as it is to just say the word “stop”, it’s not that easy. Somewhere within me is a belief that I deserve to be treated poorly; it’s a belief that overpowers any logical process, or even any desire. No matter how much we dream of a pain-free life, somewhere in us is the belief that we have to carry a burning ember in our closed fist, and no matter how simple we make the instructions (“Just open your hand.”), we continue to serve the original belief. It’s a limiting (and limited) existence, but it’s also very, very common. Holding onto detrimental beliefs is like walking in a well-worn rut, yet great things can happen when we escape it.

Americans love our icons. And so we iconize the civil rights movement with Martin Luther King, Jr. Day and replays of the “I Have a Dream”. Iconography is nice for putting a fine point on something complex, but it all but ignores the thousands of others who played critical roles in the civil rights movement. But more importantly, it enshrines the icon at the peak of their effect. When we think of Dr. King, we think of the March on Washington. We think of “I Have a Dream”. We think of Montgomery and the Nobel Prize. We think of Martin Luther King, Jr. breaking down barriers with non-violence, eloquence, passion, and compassion. We don’t think of him as terrified. We don’t see him in moments of powerlessness. Icons don’t weep for themselves, and so we ignore the deep valleys of depression that King suffered. As an icon, King was like Gandhi, walking directly into the fray with no concern for the consequences. But as a man, King required spiritual and political counsel to nudge him towards many of these actions.

On the night Rosa Parks was arrested in Montgomery, local black leaders decided that a boycott of the Montgomery bus system would be their political response. They elected Martin Luther King, Jr. to organize the boycott. King was new to Montgomery, and so they assumed he had no local ties that he’s refuse to sever in furtherance of the boycott. Also, King was educated, eloquent, and had deep family connections to clergy and academia throughout the South. Give these qualities, King should have been able to organize the boycott and keep it going for as long as necessary. Simple. But within a month, King’s home was firebombed. He was arrested after a minor traffic violation. And quickly, things began to fall apart for him. Because the very thing that black civic leaders in Montgomery saw as strategic advantages in Martin Luther King, Jr. were becoming his undoing. King was a family man with an infant daughter; now he had placed his family directly in the path of violent terrorism. King was well-connected; now he worried about tarnishing his family reputation with arrests. King believed in non-violence; now he was facing the consequences of that ideology. It’s one thing to believe in the power of turning the other cheek, but another entirely to take a punch and actually do it. And King began to waver. Hints of depressions that would run far deeper and longer later in his life appeared, and the boycott workers’s faith in King began to erode. His role was simple: keep the boycott going in a non-violent manner. But for King, it simply wasn’t that easy.

It’s compelling to wonder if King had eventually given in to his impulses and the boycott unraveled and fell apart, what might the world look like today? Similarly, what great movements has the world missed out on because some great leader had the voice of their father in their ear, telling them not to sully the family name in the interest of political gain? How many leaders have shut themselves off from obvious success because of the drone of a constant, limiting voice? The Montgomery bus boycott lasted a year, but it was clearly an early tipping point for the civil rights movement. Yet it was threatened by the voices in King’s head that had been raised on cooperation and segregation and racial hierarchy. Never mind that King knew that racial and socioeconomic justice was critical for the people of America. Despite the fact that equality was a consuming dream throughout King’s life, it met resistance when it ran up against years of family traditions and academic training. It took Bayard Rustin, noted civil rights organizer and pacifist, to Montgomery to convince Dr. King that literal “disobedience” and its consequences (arrests, retribution, violence, sullied reputations, etc.) were the necessary product of social movement. Rustin reached into his Quaker upbringing, his work with Gandhi, his philosophical readings, even his own arrest two years before for homosexuality. He pushed King to realize that success would only come when King accepted those consequences. What Rustin really did was talk over the voices and the history in King’s head.

By the time of his death, Martin Luther King, Jr. had been arrested more than 30 times. He had earned the scorn of many members of the Southern black clergy, particularly established clergy of his father’s generations. Many members of the clergy did not want to rock the boat, and used the violence waged against demonstrators as evidence that the civil rights movement was too aggressive. This disapproval was the kind of thing that had nearly stopped King in Montgomery. By the time of his arrest in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963, King’s now-famous “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” unrepentantly explains the importance of his position. The voices that shackled his dream were removed. As the years went by, King even came to realize (sadly, unwillingly) that he would become a martyr for the cause of equality. If any voice could justifiably silence a dream, it is the awareness of martyrdom. And yet King continued to follow his dream until his actual martyrdom on April 4, 1968.

There’s an old country phrase: “You never get past your raisin’.” Our history sometimes defines us so rigidly, our dreams can’t mold us into something new. We are no match for our demons. We are no match for our prejudices and our doubts. Our present moment is barely visible compared to the mountain of moments that preceded it. But those moments were bestowed upon us; they were the thrust upon us as impressionable children. They were created in moments of fear and awe and in the midst of ignorance; it’s the scarring power of trauma. Even non-traumatic origins like “this is how we’ve always done it” feels monolithic, impenetrable. But our dreams are not what’s placed upon us. They are destinations we’ve created from within the life we’ve been given. Our dreams are what we should be following, as they’re unique creations (manifestations, even) of ourselves. But to reach them, we have to lose the meaning of the history that holds us. For Martin Luther King, Jr. it meant shedding the images and beliefs he had about how a minister comports himself, and the fear of consequences over civil disobedience. But we each are held by a history we did not choose. Every one of us is limited by a belief we did not adopt by choice. And if we shed it, we can follow our dreams. And life can be – finally – simple.