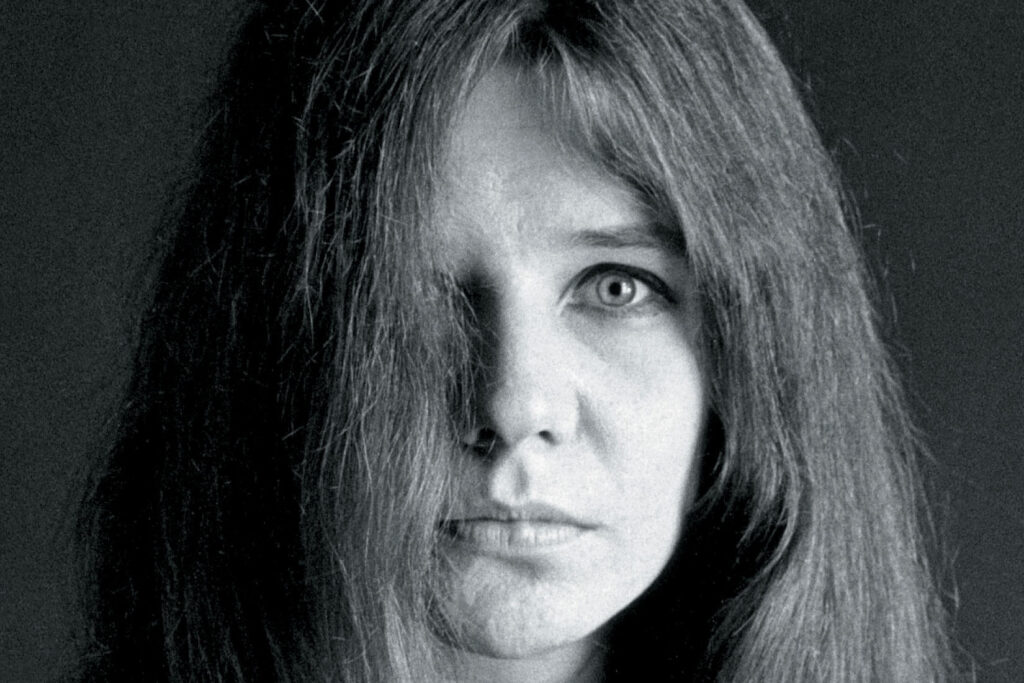

JANIS JOPLIN: January 19, 1943 – October 4, 1970

“Playing is just about feeling. It isn’t necessarily about misery. It isn’t about happiness. It’s just about letting you feel all of those things you already have inside of you but are trying to push aside because they don’t make for polite conversation. But if you just get up there… that’s the only reason I can sing. Because I can get up there and I can just let all of those things come out.”

– Janis Joplin

I am, by nature, a violent waker. More often than not, I don’t “rise” from sleep so much as I “erupt” from it, with flailing limbs and wide eyes, sweat, and lashing confusion. It is pronounced enough that my family treads very lightly during the infrequent – and usually unscheduled – moments I’ve fallen asleep. And the biggest irony is that this violent waking generally follows the most delicate disruptions. Perhaps it’s a child walking softly through the room. Or someone gently closing a nearby door. Or maybe it’s just a brief moment of apnea. Whatever it is, some hyper-vigilant part of my brain clearly watches for the slightest shifts in vibrations and alerts me with a jolt of adrenalized panic. Which is not to say that I can never sleep. In fact, the opposite is also true; I can sleep through chaos. I have slept through rock concerts. I slept through Apocalypse Now in the theaters – twice. I once fell asleep while getting a cavity drilled. My brain operates with a fatalist’s resolve; it is highly-attuned to manageable crises, and completely shuts down in the face of overwhelming chaos.

Which should explain, in part, the last five years.

I started this project at a time when I had run my life off the rails. I had compromised my own growth and health and happiness to an extent where I needed to force myself to focus on positivity and gratitude. This project was a violent awakening to my own life, and it helped. There were peaks and valleys during the three years that I was writing, with brief bursts of effort following the latter until things began to settle down.

But as 2016 wore on, I noticed massive changes around me. Contention. Division. Hostility. I watched friends and family fight and divide over politics and religion. It felt like I couldn’t recognize half the people I knew, and the other half was too irritable to be enjoyable. And amid the chaos, I just went to sleep. As if the doctor had given me a terminal diagnosis. As if the plane was heading for the trees. As if the car was in a broad slide on a crowded icy highway. With no control possible, I just… shut down. I stopped writing. I stopped drawing. By the time COVID-19 arrived to set fire to this already-overflowing outhouse, I quit my band and spent a year doing (literally) nothing creative.

So when I started listening to Janis Joplin frequently about a month ago, I knew it might be my soul telling me something. The fact that her birthday fell on the first day of the calendar year that did not have any entry in this process felt like a sign to help me understand what the creative shutdown meant.

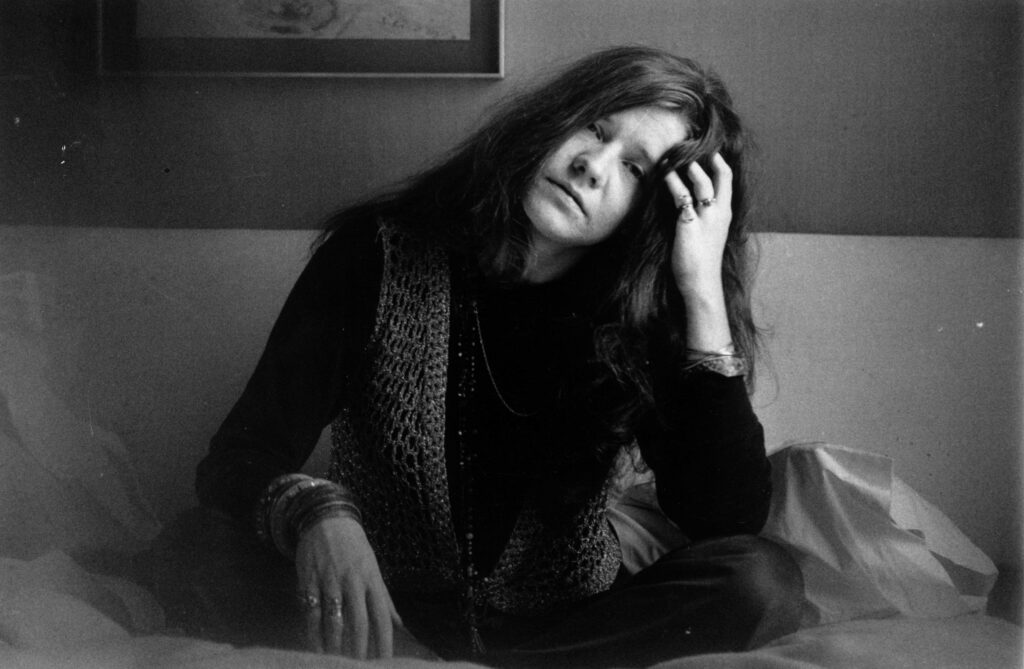

I’ve been a Janis Joplin fan for as long as I can remember. I was well into my 40s before I realized that, as a singer, I used vocals to convey emotions that I would otherwise be incapable of expressing. In most cases, these were emotions I’m not able to understand or identify in the real moments of my life, but only from a safe distance – like a written page or a song. So a singer like Janis was tailor-made for me. She gave every vocal performance every bit of the emotional resonance that it needed, packed to near-bursting with as much intensity as it could handle. The story of Janis Joplin isn’t about damage so much as it is about honesty and precision.

Janis was born in Port Arthur, Texas in 1943 when it was a prototypical Texas oil boom town: heavily-segregated, filled with proselytizing Christians, and encircled by dive bars and whorehouses. Janis was raised in a kind and loving home and seemed to quietly fit into Port Arthur life – until puberty hit. By the time she got to high school, she was pudgy, acned, with wild, difficult-to-manage hair. Her Church of Christ upbringing wrestled with early bisexual urges. Her lifelong creative streak gave her the confidence to dress and act the way she wanted, which ran directly counter to Port Arthur’s staid conservatism, overt racism, and dominant chauvinism. Janis found herself ostracized in every way except for her love of blues music, which she shared with some of the local boys. Hitching a ride one night with a few male classmates to see a blues show in Lake Charles, Louisiana, she returned with an unearned reputation as the school slut. Rumors swirled, and she earned the nickname “Beat Weeds” as a reference to her (allegedly) foul-smelling private parts. Despite an obvious talent for music that she would showcase in coffee houses around Port Arthur, Janis could not escape Port Arthur’s intransigently conservative nature. (Years later, fellow classmate Jimmy Johnson would become an NCAA championship and Super Bowl-winning coach. Even after decades of the highest success he could achieve in his field, when asked about Janis – dead some three decades, at that point – he could muster no more empathy than to refer to her only as “Beat Weeds” and talk about her promiscuity and her lack of personal hygiene. This was Port Arthur, in a nutshell.)

Janis tried attending a technical college in nearby Beaumont and then transferred to the University of Texas – Austin where she was greeted with a little curiosity – and a lot more resentment. The UT newspaper The Daily Texan wrote an article about the free-spirited girl who always wore jeans and carried an autoharp everywhere she went so she could indulge in song whenever the mood struck. On the other hand, conservative frat boys resented her unwillingness to subject herself to the beauty standards of the day, and they nominated her for an “Ugliest Man on Campus” competition. Fraternity members plastered posters of her all over campus; Janis won the contest.

This is not to say her eventual move to San Francisco with musician friend Chet Helms was an escape. Janis wasn’t fleeing from Texas so much as just following an obvious path of least resistance. Janis never “fit in” in Texas. And like anything bent against its nature for too long, her only options were to break or to break loose. Which she did in San Francisco, where the beat sensibility allowed her to indulge every creative, sexual, and behavioral inclination she had. But the post-Beatnik/pre-Summer of Love San Francisco had a strong undercurrent of drug abuse, and Janis quickly fell into a series of addictions that would plague her for the rest of her life. Within two years, she retreated to Texas. She weighed 88 pounds and couldn’t think of a single friend she’d made in San Francisco. Once again, she just didn’t seem to fit in.

It’s tempting to assign Janis’s addictions the blame for her difficulties with society, but the more likely truth is that heavy drug use was the fashion of the time, and addiction was just its hefty price tag. Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, and Pig Pen McKernan were far from outcasts in their lives, but all fell prey to addiction – and died – in the same period, all at the same age. And while that addiction and its consequences are horrible, it feels misguided to say it was the result of not fitting in; “not fitting in” was almost a perfect embodiment of her time. Nothing Janis was doing was harmful or even mildly damaging to others, particularly by today’s standards. That a woman wearing jeans every day to class could merit a feature article in the student paper at one of the nation’s largest universities seems almost incomprehensible today. But these were Janis’ crimes, and these were what made people reject her. That she refused to be more like they wanted her to be. That she refused to live apologetically for not looking like they wanted women to look. That she chose to wear her hair however she pleased and didn’t at least pretend to give a damn what the boys liked. She wasn’t hurting anyone, and that was enough for her; the rest of her life was on her terms. And people hated that they couldn’t control her more, and so they attacked and attacked and attacked until she returned home to Port Arthur, defeated and strung out.

Upon her sad return, Janis desperately tried to fit in. She tamed her unruly hair into a perfectly-coiffed beehive. She bought skirts and business blouses, enrolled in an anthropology program at nearby Lamar University, and took secretarial work as a keypunch operator at an oil company.

“Fitting in” lasted little more than a year.

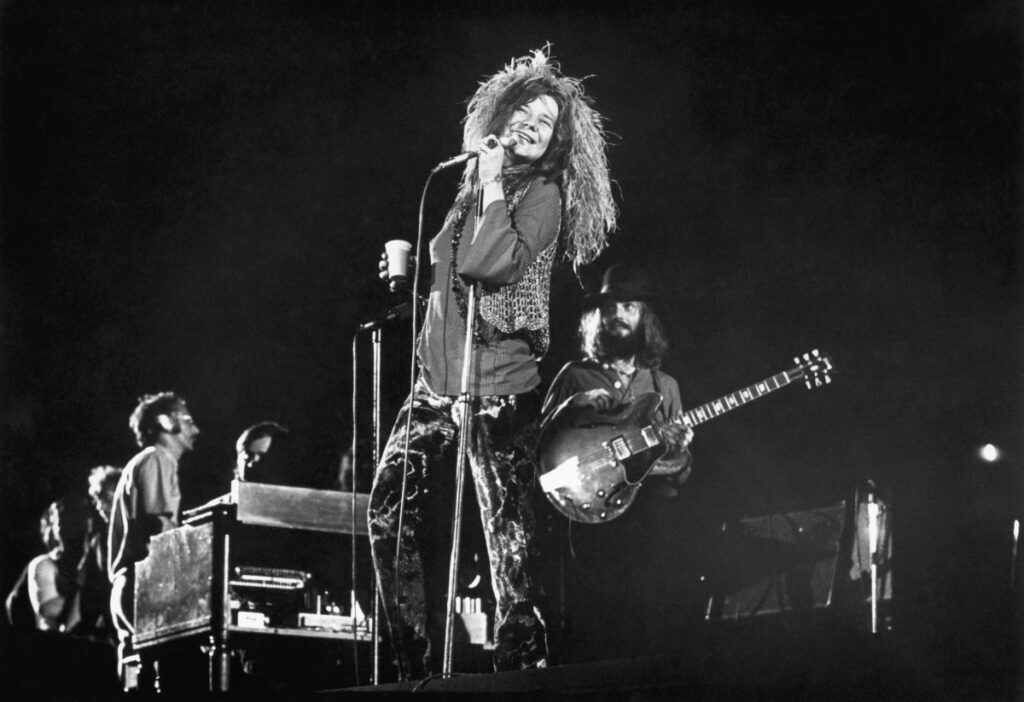

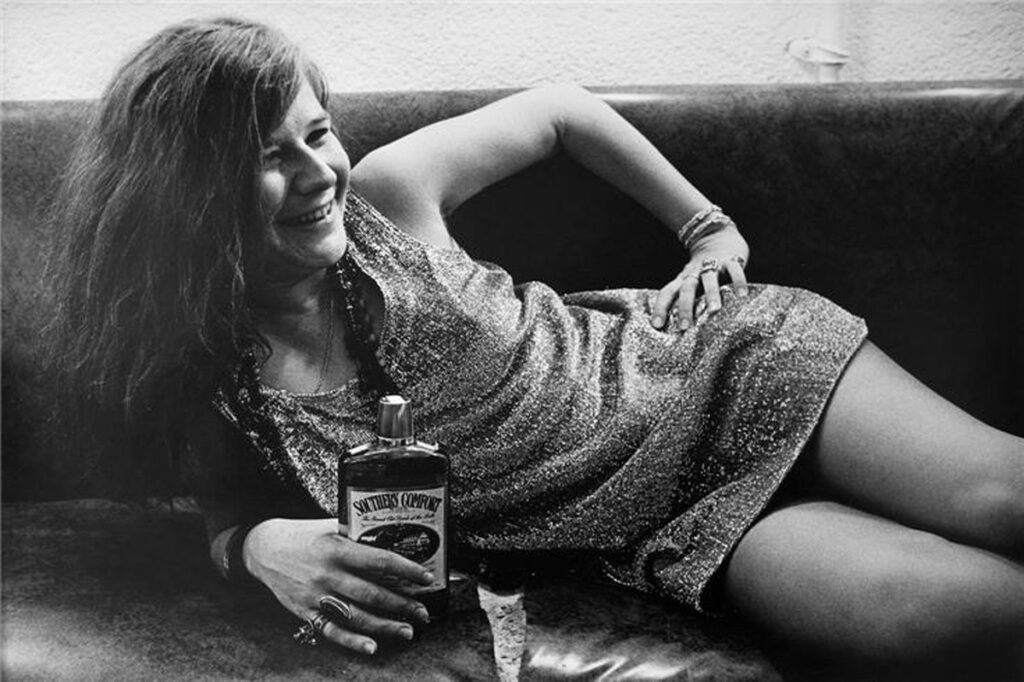

When Chet Helms – now a prominent promoter in San Francisco – tracked her down and asked her to return to San Francisco and front rising local band Big Brother & The Holding Company, now-sober Janis packed up and headed west – against the advice of her parents, co-workers, and the psychiatrist who had been treating her addiction. But within a month, Big Brother & the Holding Company were headlining at the legendary Avalon Ballroom, and by July they were playing large outdoor festivals. And it was here that Janis cemented the attitude that would propel her to super-stardom for the rest of her far-too-short life. Instead of trying to fit in, Janis became gloriously, aggressively, flamboyantly herself. She wore whatever she wanted to wear, whenever she wanted to wear it. She wore makeup – or didn’t – whenever and however she wanted. She accessorized her outfits with legitimate accessories as often as she handmade something into an accessory. If she accessorized at all, that is. She took drugs and drank as often as she wanted. She slept with everyone that interested her: men, women, famous, not famous, attractive, ugly. It made no difference to Janis; as long as she was attracted to them, she’d sleep with them. And her singing became more and more honest. Despite beating her vocal cords to holy hell with a constant flow of cigarettes and Southern Comfort, her voice gained prominence and was compared favorably to her idols like Big Mama Thornton and Ma Rainey, all mezzo-sopranos who defied easy classification as they could – and did – contort their bodies and throats into whatever was needed to communicate the song properly. Within a year, Big Brother & The Holding Company had a prime slot at the Monterrey Pop Festival, a major-label contract, and an album on the way.

By the time the eponymous first album dropped, the legend of Janis’ performance at Monterrey had gripped the nation. There were some minor hits off the album, but all eyes were on the second album, Cheap Thrills, which would include some live Janis performances. But as so often was the case, Janis was again having trouble fitting in – this time with her own band. Big Brother & The Holding Company were a good (but far from great) band. And Janis was a great singer. It’s apparent on those first two albums that Janis is elevating the entire band with vocal performances so honest and so raw that the band feels almost amateurish, by comparison. This didn’t become a problem for Janis, who was now emboldened with the power of following her own star. She quit Big Brother & The Holding Company and assembled a new band with Paul Butterfield’s former guitarist, Mike Bloomfield. The new “band” included top studio and touring musicians and a full horn section, which Janis wanted to echo the sounds of the popular Stax and Volt R&B records of the day.

By the time I Got Dem Ol’ Kozmic Blues Again Mama! was released, Janis had pretty much crafted her own perfect world by unflinchingly, shamelessly, and ceaselessly being Janis Joplin. She overcame the insults to her appearance by dressing as wildly and flamboyantly as she wanted. Suddenly, the girl nobody wanted to look at was The Great Golden Hippie that mesmerized everyone. She overcame objections to her desirability by sleeping with everyone she was interested in. Most importantly, the girl who was overlooked and ignored and marginalized and pushed aside her whole life now had the ability to communicate as purely and honestly and with as much emotion as she cared to muster. And people listened! They hung on her every word.

It’s difficult to set aside Janis Joplin’s premature accidental death, but I think it’s a necessity when considering the lessons of her life. Sadly, almost every article published in recent years is about “the sad, tragic party life of Janis Joplin”. This is true enough, in a sense. Any life cut short, regardless of the reason, is a tragedy. And we’re right to mourn any admirable public life cut short. James Dean’s car accident. Buddy, Ritchie, and the Big Bopper’s (also, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s) plane crash. Duane Allman and Berry Oakley’s motorcycle crashes. Johnny Ace’s suicidal game of Russian roulette. All were sad and tragic. But most stories of Janis’s life focus on how her addiction numbly shuffled her to an early death with just momentary bright spots on stage and vinyl to temporarily carry her through. These stories persist despite repeated stories from friends and colleagues about how assertively and uncompromisingly Janis chased her own joy: in her clothes, in her activities, in her friendships, in her lovers, in her locations, and unfortunately, even in her addictions. To ignore that is to reduce the real message of her life.

Because the message of Janis is wailed over and over in smoky pitch-perfection in her music. Janis reminds us that our power as an individual is to take all of those feelings we have inside ourselves and share them as honestly as possible. Not just in our words (sung or spoken), but in how we exist every minute of every day. Janis’s life was one great work of art, by that standard, and so is yours. So is mine. So is everyone’s, and the goal is to take all of the things inside us that might make others uncomfortable or confrontational or downright cruel, and – as long as they’re not hurting someone else – follow and defend those impulses with everything we’ve got. Because those impulses are who we are. And the world has no problem shutting down those impulses. In fact, it actively tries to.

That has been the last five years for me. All of the anger, all of the cruelty, all of the willingness to destroy friendships and families and the innate common humanity between human strangers all in the name of some desperately-fragile need to… what? Win an argument on Facebook? Quell that persistent sense of unease that comes from uncertainty? And just as Jimmy Johnson and the other assholes of Port Arthur tried to beat the voice out of Janis to assure themselves that crew cuts and high school football and the occasional violating grope of a woman was an acceptable certainty, we’ve taken the last five years to beat the voices out of everyone who disagrees with us. And now we’re seeing how that ends up, with isolated factions attacking themselves. This long nightmare, fueled by algorithms and a fear of uncertainty, has removed us from each other. And in doing so, has removed many of us from ourselves. I know that I have progressively silenced myself because the world was too harsh and too cruel to want to participate in, and it was a harshness and a cruelty that I could neither control nor fix. The last five years have been the dental drilling I slept through.

And when I considered writing again, I experienced many, many missteps. I believed I couldn’t write anymore, because I couldn’t contain my thoughts into something elegant and easily readable. (You know, the way social media tells you a post should be.) But this is a post about Janis. And for Janis. It’s not for the algorithms, and it’s not for you. It’s for me. And all the things inside of me, quieted for five years are going to come out and demand their time in the spotlight. Whether anyone else likes it or not. And so I sat down this morning and just started writing. (Which was the intent of this project in the very first place.) And now the parts of me that I’ve silenced for five years in deference to the ever-diminishing polite conversations in society are coming out. And they’re coming out my way.

Honor everything inside of you.

Don’t hurt others.

And let it all out, in any and every way you see fit.

Love yourself and share yourself with the world… whether they like it or not.

That’s what Janis Joplin can teach us.