MUHAMMAD ALI: Born January 17, 1942

Moments ago, Seattle Seahawks cornerback Richard Sherman just tipped the final pass and forced the game-clinching interception in the NFC Championship Game against arch-rival San Francisco. The pass was thrown to one of Sherman’s biggest rivals, Michael Crabtree, which made the play even more powerful for Sherman. In an interview immediately after the game, Sherman loudly boasted, “I’m the best corner in the game. When you try me with a sorry receiver like Crabtree, that’s the result you’re gonna get. Don’t you ever talk about me.” Immediately, the social media world exploded with comments about how classless the comments were, and people in numerous channels branded Richard Sherman a “thug”. As an employee of a Seattle-based company, I have been given insight into the Seahawks I would have otherwise not known. Richard Sherman has been one of my favorite introductions. His backstory is pure Americana. His rise to football prominence from his fifth round draft is a testament to his work ethic. His blog is insightful, intelligent, and entertaining. His reputation off the field is impeccable. Prior to tonight’s interview, Sherman was known for never uttering a swear word in a post-game interview. His charity work is genuine and he is closely involved with all of his foundation’s efforts. Richard Sherman may be a lot of things, but a “thug” is far from accurate. As I watched the social media universe explode in frustration of Richard Sherman’s “thug-like” behavior, I thought about one of Sherman’s heroes, Muhammad Ali, and I wondered how we would handle Muhammad Ali today.

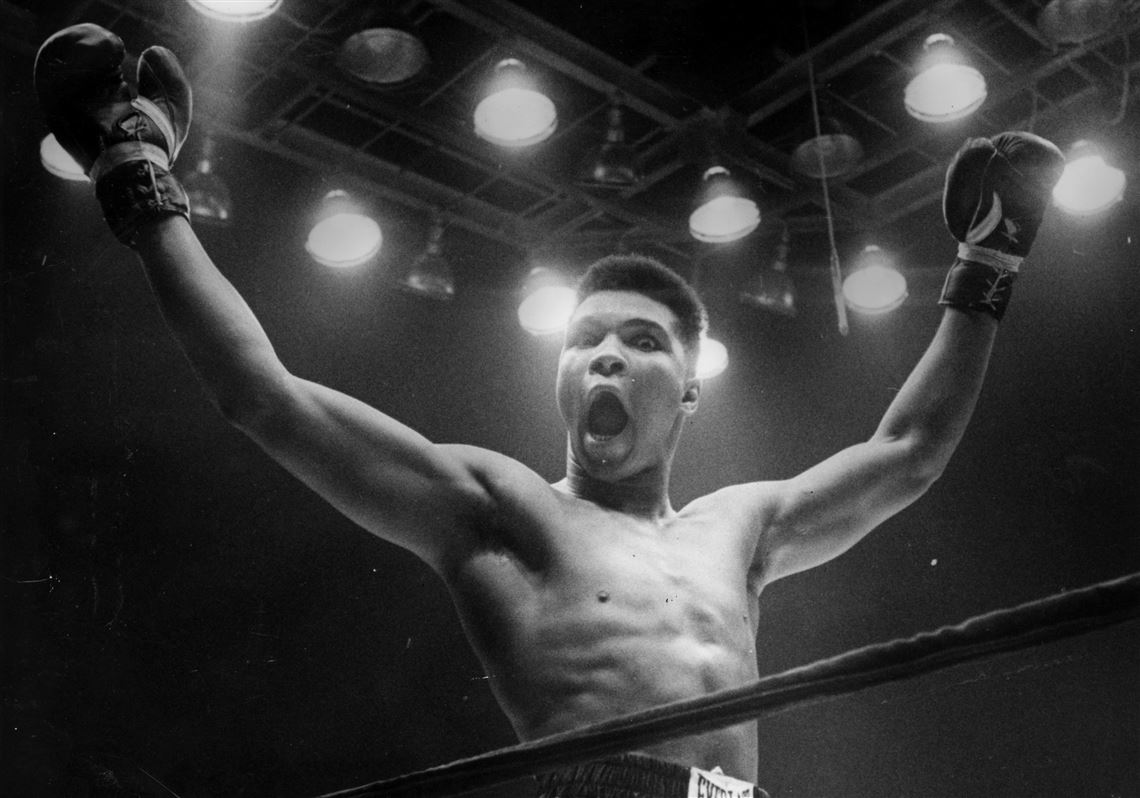

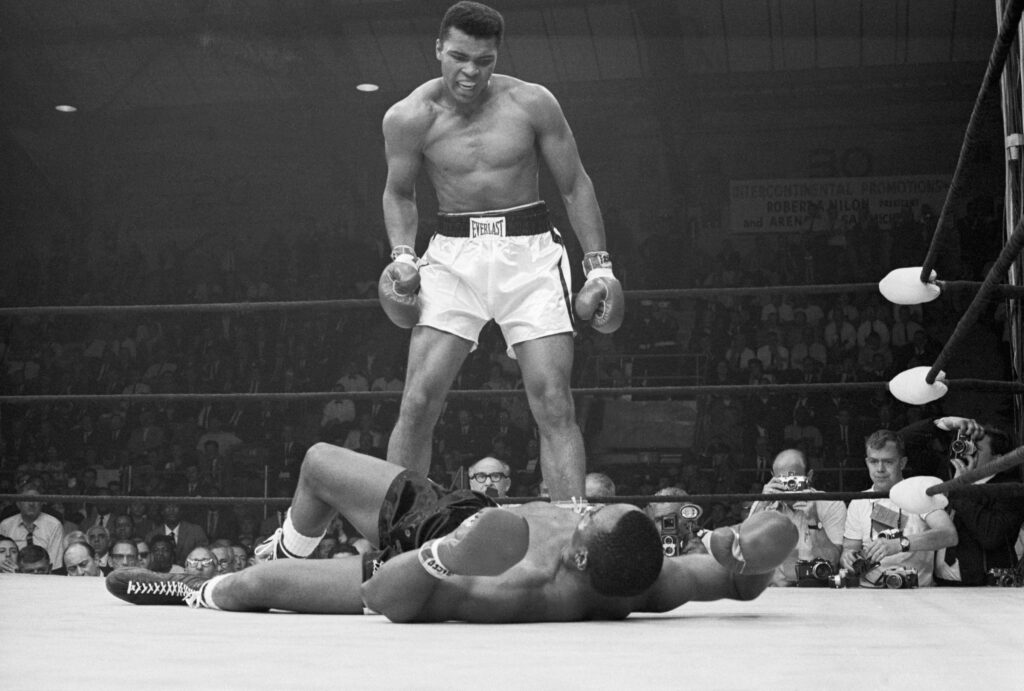

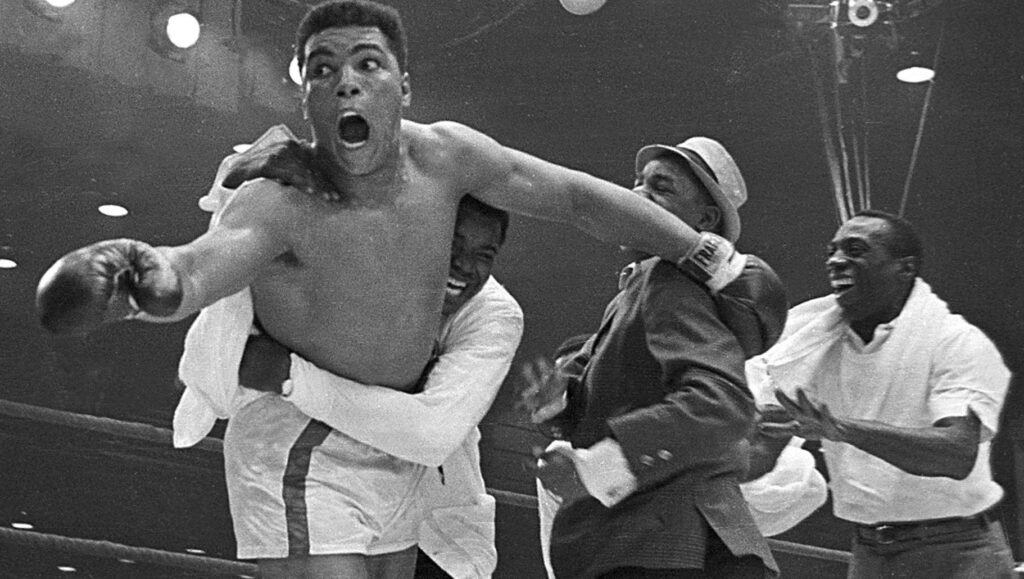

As a lifelong boxing fan, I’ve had numerous arguments about the greatness of Muhammad Ali. I am a die-hard Ali fan. I consider him the legitimate holder of the title The Greatest Of All Time. My grandfather was born in 1920. He preferred Joe Louis for that title. More than anything, he disliked Ali because of Ali’s outspokenness. Arriving onto the global scene with a gold medal win in the 1960 Olympics, (then-named) Cassius Clay was never silent about his awesome skill. It was an affront to the gladiatorial nature of the sport; fans expected boxers to risk their lives in the ring without complaint for our entertainment. Commenting on one’s own ability – positive or negative – was a sign of weakness. Like Jack Johnson more than fifty years before, Clay’s claims to greatness early in his career infuriated both boxing fans and racists. People derided his claims. They searched for a challenger to shut him up. They rooted for opponents they would otherwise hate. By the time Clay earned his first title fight against Sonny Liston, he had created an army of Liston fans, despite the fact that Liston was more thuggish, mobbed up, and unlikeable than almost heavyweight champion in history. And despite being a 7-1 underdog, Clay beat Liston for six straight rounds. Rather than remain humble, Clay leaned over the ropes at the end of the sixth round and screamed to the press, “I’m gonna upset the world!” Liston, in return, spit out his mouthpiece and refused to come out of his corner for the seventh round. Ali danced around the ring in celebration. Taunting his opponents, predicting victory, dramatic flights of fantasy about his greatness, outright bravado, and a demand to be recognized – these would be Ali’s tactics for the rest of his career.

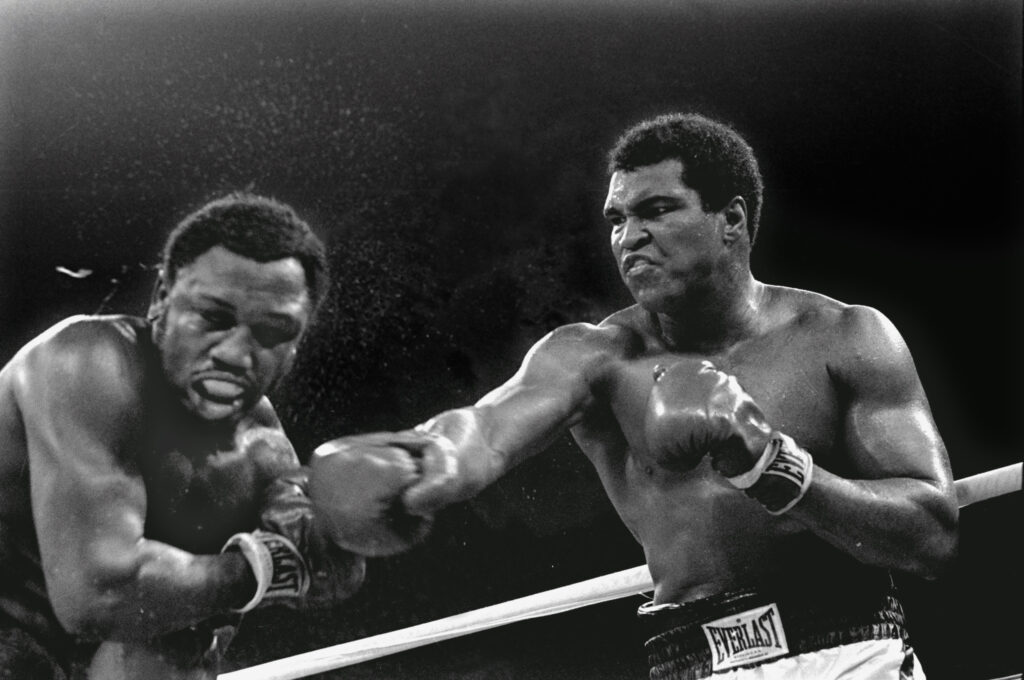

The price Ali paid for these tactics has been examined for decades. So have the ramifications of an African-American athlete demanding a nation’s respect. But what about the personal level? What did it mean for Ali to proclaim his greatness? What did it mean for him to envision his victories and then act out those visions to the media, to America, to his opponents? At their most basic level, Ali’s proclamations were for him more than anything. One needs to only watch Ali’s press conferences in Zaire in 1974 to understand this. Older, slower, and facing the strongest opponent of his career, Ali’s press conferences would always begin with Ali claiming greatness and inevitable victory, but the longer the press conferences would last, the more tentative his words would sound, the less forceful his voice, the less descriptive his visions. Ali in Zaire was a testament to the power of positive self-talk. Ali surrounded himself with the people of Zaire, and he talked them into chanting “Ali! Kill him!” in their native language. In the weeks leading up to the fight, Ali surronded himself with positive talk and positive self-talk. On the night of the fight, even his cornermen and supporters were convinced that Ali was in trouble. According to Normal Mailer, as Ali awaited his call to the ring, he said to the silent room, “Why is everyone so quiet?” And then he led the room in a round of Ali bravado. He had the room testify to his skill and to his speed. He envisioned beating Foreman. And he did.

Part of what we dislike about Ali and Sherman’s “classless” behavior is due to how we want to view our athletes. We want our athletes the way we want the cowboy heroes in western movies to behave; we want them to feel invincible but not to need the validation necessary to believe in themselves. That belief must be inborn, and to share it in any way is classless. The very idea is ridiculous. How frequently do we deny ourselves the right to own our strengths because it would seem classless? How quickly do we let someone else’s proclamation of positive self-talk pass by us because we convince ourselves it’s inappropriate? I have recently had two conversations about “selfies” with people I care about. In both cases, the people taking selfies did it because it made them feel like – for a few seconds out of each day – they found reward in presenting themselves attractively for the camera, and they wanted to share that with others. Both people described the feeling as being valid and valuable, but they both seemed shamed by the need to so that. For my part, I felt sad. Because neither of them ever considered sending me one of their selfies; they knew I would not give them the positive feedback they wanted. They are attractive people, becoming increasingly more attractive, and both had to carefully choose who they shared their selfies with because people like me refuse to allow them a moment or two a day where they can embrace their own awesomeness. If all success stories are based in the belief in achievement, how many success stories do I regularly hinder or derail with my unwillingness to simply allow someone a moment to say, “Damn, I’m good!” and believe it?

Call Ali classless. Call Richard Sherman classless. Call selfies a shallow, desperate plea for attention. But if we re-frame it for a second, these are powerful statements. These are examples of a person openly embracing their greatness for a moment. It’s a braver decision than we want to give it credit for. And if restricting those thoughts to within our head where they can’t be tested and validated is “class”, then perhaps we’d all be better off boorish.

Boorish and proud.