FRECKLES BROWN: January 18, 1921 – March 20, 1987

Some moments of gratitude are simpler to define than others. They either speak to something very primal within us, or something purely aesthetic, or they echo a challenge we’re facing. They’re the kind of moments that don’t require much context; they either fit into our worldview or they don’t. If they do, they generally point to broader philosophical or ethical directions. For instance, I’m nearing my 45th birthday and I had stopped doing any writing (or really, anything creative) over a decade ago. Now, I find myself trying to recapture something that I feared was lost forever. Many days, I slog through my writing attempts with the heavy legs of a sedentary old man. But once in awhile, I grab a phrase or a paragraph that feels remarkably honest. The words pour forth and remind me what it was like to be carried away as a writer or an artist, and I remember – even if only for a second – what it means to write with honesty and authority. It’s like grabbing all of life by the ear, and dragging the world anywhere you want it to go. It’s empowering, and affirming. Best of all, it carries through to the readers. And in those moments, I dream of an audience reading those words and thinking, “Damn. I never would have guessed he could do that.” No explication needed, no contextual examination. Sometimes, impressive acts are best rewarded with recognition – at best, with awe. While I undoubtedly write to make an impression, once in awhile it’s nice to leave a real mark. Just to know I still can. And I can (and likely will) dig into the intricacies of this process: find out why I write the way I do and who influenced that, examine the frame of a movie or the angle of a shadow in a painting as metaphors for the tiny victories and barely-seen traumas that shaped my particular worldview. But once in awhile, I want a simpler message. I want to be able to prove to myself that I can still create, and still be good at it. This was the idea I was reflecting on when I remembered Freckles Brown.

I was about ten when I discovered rodeo. The movie Urban Cowboy and TV shows like Dallas had plunged suburban America into a frenzy of cowboy hats and Justin boots. I was already a fan of country music, but rodeo fascinated me. Seeing a rodeo in northwest suburban Chicago was pretty much impossible, so I went to the library and found two coffee table books about horses which contained text explaining the rules of equine rodeo events. I later discovered bull riding after seeing six-timeWorld All-Around Cowboy Larry Mahan compete on a rerun of The Superstars. I found out that bull riders rode one bull per rodeo (generally), and never for more than eight seconds. That they might ride in three or four rodeos in a week. And in the 20 or 30 seconds they actually “work” during a given week, they take more punishment than any other athlete takes in an entire event, including boxers and football linemen. It’s a game of intense reflexes and violent smashes against inertia. Even if bull riders are successful, they also have to dismount, a process that generally flings them in the air 8 to 10 feet. If they land on their feet, then they have to avoid getting trampled by a frustrated bull. As such, bull riding is generally a young man’s game. By the time a bull rider hits his late 30s, he’s generally had so many broken bones and suffers from arthritis enough to slow their reflexes past the point of being competitive. By the late 1960s, this was the state of Freckles Brown.

Prior to the 1967 rodeo season, Warren “Freckles” Brown was a 46-year old former World Champion bull rider. Brown had been riding bulls professionally for 30 years, and by all accounts should have been at the end of his career. Brown had regularly been a contender for the World Championship, but he’d only won once. As the 1967 World Championship began in December, Brown was not really in the running to win the title. Worse yet, the old man was in his first full season since breaking his neck in three places two years before. The injury could have been life-ending; by every doctor’s recommendation, it was career-ending. But Freckles Brown found himself back on a bull a little over a year later, and the fraction of reflex time he’d lost in recovery was barely perceptible. Brown was just happy to be competing again, when there had been so many questions about his health just a year before. There was only one problem. When the riders were assigned their bulls for the first round, Freckles Brown had drawn Tornado.

In the rodeo world, the bulls and horses are treated with equal respect as the cowboys. The Pro Rodeo Hall of Fame has a “livestock” category every year for legendary broncs and bulls. Even the scoring of a bull ride is split evenly: 0 to 50 points for the rider, 0 to 50 points for the bull. In the world of rodeo, no bull before or since has been as terrifying as Tornado. By the time Freckles Brown drew Tornado’s name for the first round ride, Tornado had thrown 220 straight cowboys. Nobody had ever stayed on him for more than six seconds. Tornado was enormous, fast, agile, and liked to spin quickly and change direction on a dime. Unlike other bulls, though, Tornado wasn’t surly or ill-tempered. In the chute prior to the ride, Tornado could be downright docile. But the moment the cowboy settled in for the ride, Tornado’s muscles would go as rigid as oak and he would prepare to blow out of the gate with every ounce of energy at his disposal. Tornado was more than a wild animal; Tornado was an athlete. He was also notoriously dangerous because he spun so quickly. When cowboys would fall off, Tornado kept spinning and often stomped cowboys accidentally. And so nobody expected Freckles Brown – fifteen years older than the top cowboys, a few years past his prime, and two years from a near-paralyzing injury – to ride Tornado for eight seconds. The fear was whether or not Tornado would inadvertently kill the former Champion. In an arena filled with people, only Freckles Brown seemed unconcerned to be facing off against the most notorious bull in the history of rodeo.

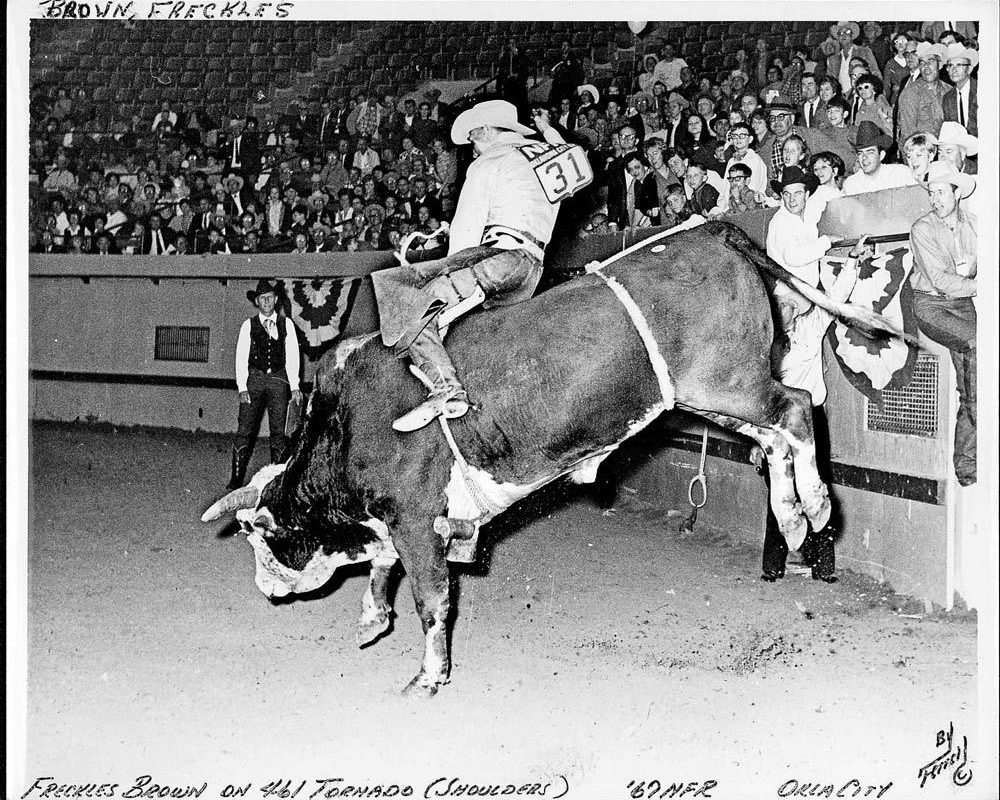

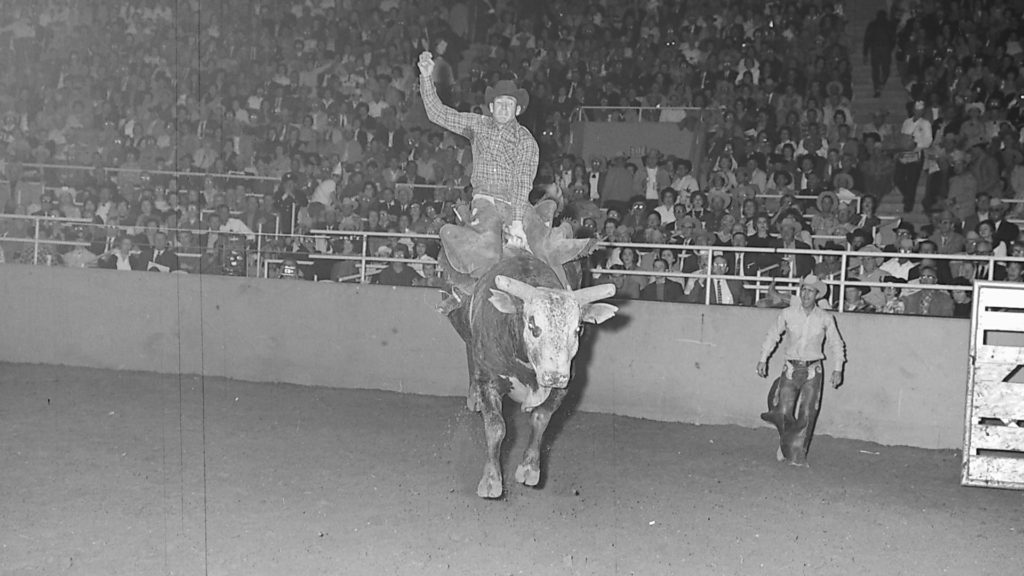

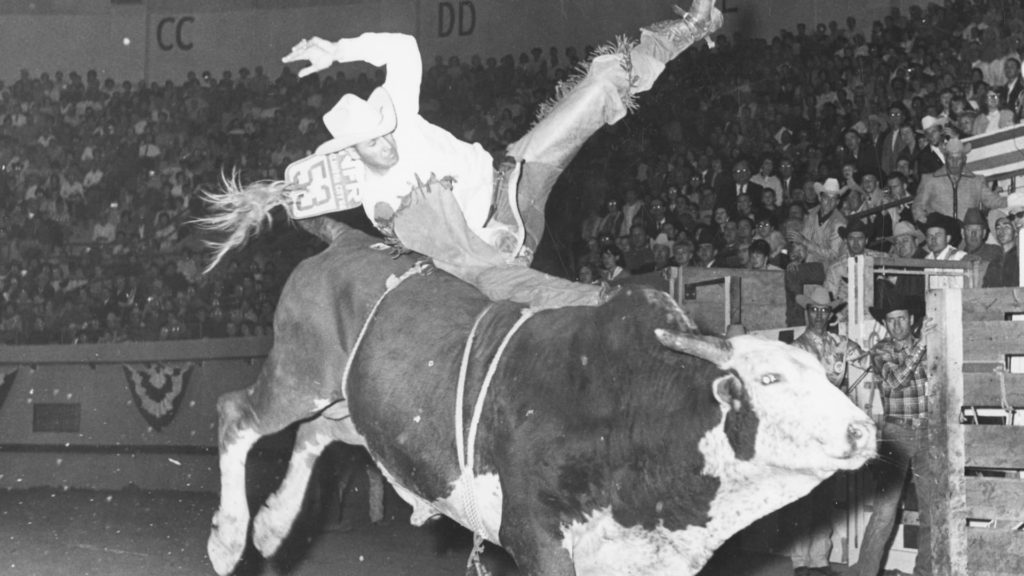

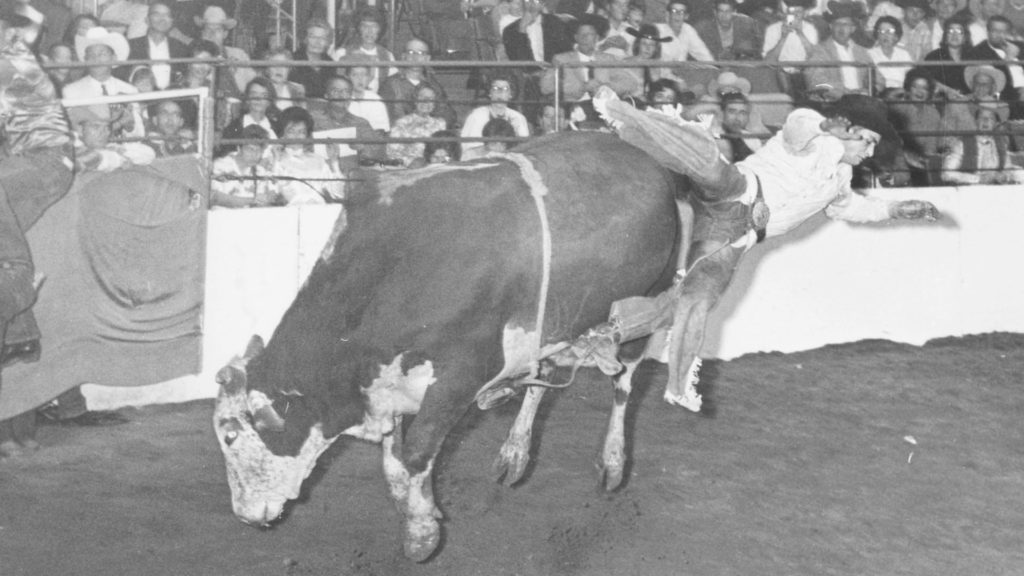

Rodeos are a notoriously rowdy affair. People cheer loudly for the entire eight second ride of most bull riders. Accounts of that night describe the arena as “deathly silent”. Flying out of the chute, Tornado began throwing himself violently back and forth. But Brown hung on out of the gate. Then the one second mark. Then two seconds. A photographer in the arena floor grabbed a photograph, the only close-up of the moment. Tornado went into a spin; the move he used to throw cowboys off-balance. Freckles Brown spun with him, never showing signs of being off-balance. Three seconds. Four seconds. Tornado began spinning and then changing directions. But Freckles Brown never got off-balance. His body stayed straight and aligned with the thrashing beast. Five seconds. The crowd begins to cheer. Six. Louder now. Tornado spins and bucks in monstrous leaps. Brown remains squared away, his back straight vertical. Seven seconds. The crowd erupts. Tornado, who has never had a cowboy on his back that long thrashes even harder, but Brown is in the groove now. No move the bull can make will be a surprise. Forget the broken neck. Forget the ten broken legs, the smashed hips, the torn ligaments, and the arthritis. Forgot the 46 years and the concussions. Freckles Brown is doing what he’s done for 30 years, and he’s doing it better than he’s ever done it before. Better than anyone has ever done it before. There is no conscious thought, there is no planning, there was no strategy to make history. Brown simply reaches inside and relies on every instinct he’s ever hard-earned over a long career, and does the impossible. The buzzer sounds, and the volume of the arena is deafening. The packed arena has witnessed history. Freckles Brown has done what no cowboy before could do, and what no cowboy after him would ever be able to do. He will not be the Champion of the season, but that’s irrelevant; Freckles Brown just made history.

We know why Freckles Brown rode Tornado – it was his job. The bigger question, however, is “why was Freckles Brown there in the first place?” Certainly, when circumstance and opportunity met that day in December 1967, Freckles Brown delivered a performance for the ages. But why was he on the stage at all? Freckles Brown was a man of very few words, and even less prone to introspection. The reason he gave most often was as expectedly direct and unadorned: he was riding bulls because he knew he still could. Because there are moments in our lives when we have to give up on something we love to do because we can no longer do it. We eventually grow too old to ride bulls. We grow too unpracticed to create art. Too blind to drive, too old to be silly, too established to be spontaneous, too indebted to retire. But in most cases, these are slow descents which take years to reach the terminal state. Until that moment when it’s officially too late to get back what we once had, we can look to Freckles Brown, who not only rode bulls well into the slow descent towards “too old”, he rode better than anyone ever did – before or since. Before we assume it’s too late, maybe we can keep trying… with the belief that we know we still can. There may be some real magic there.