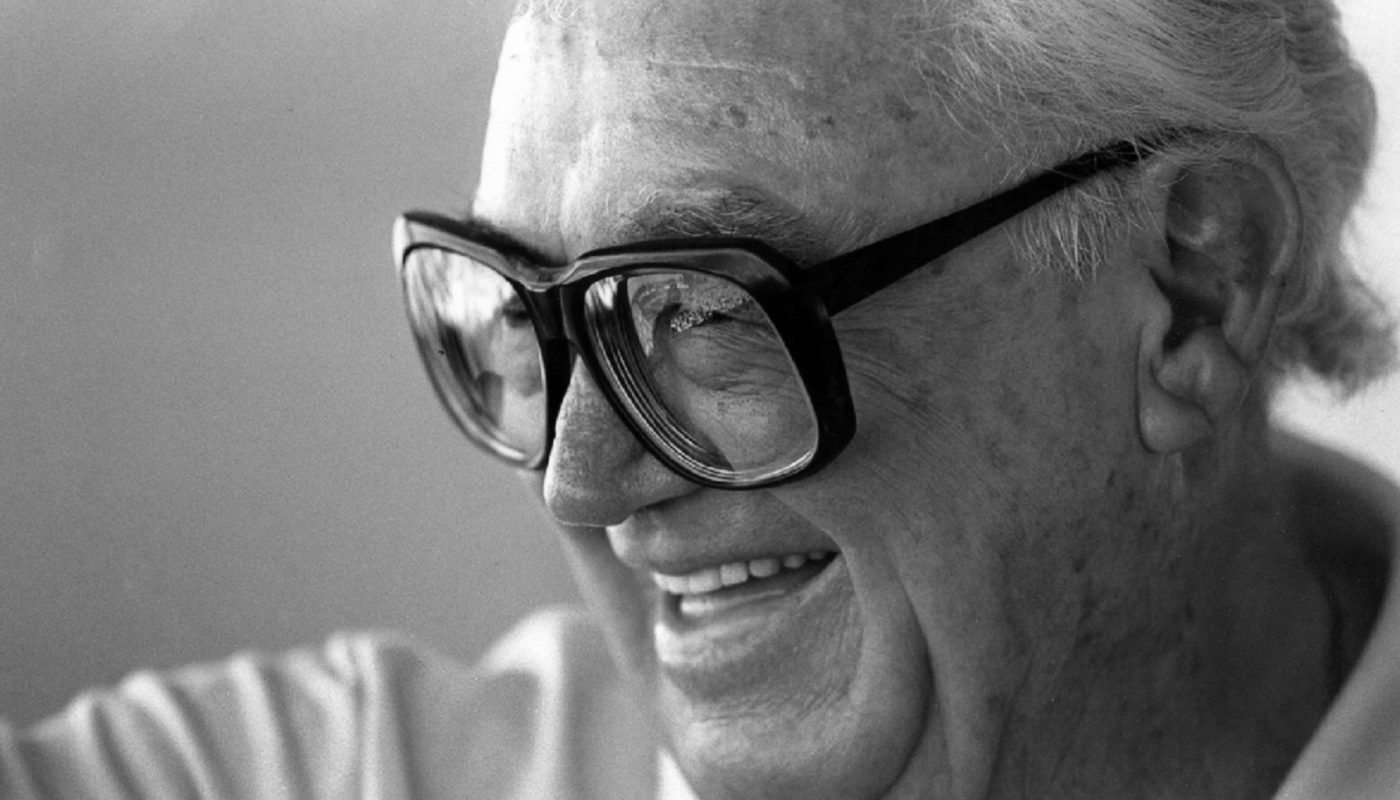

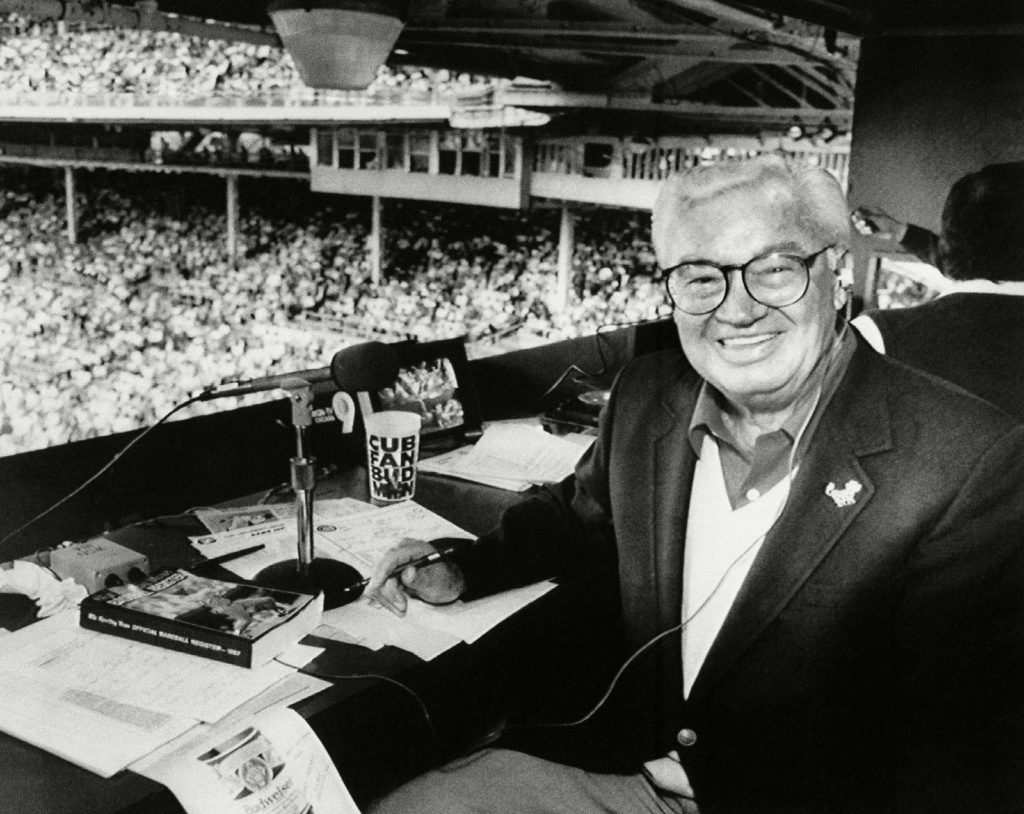

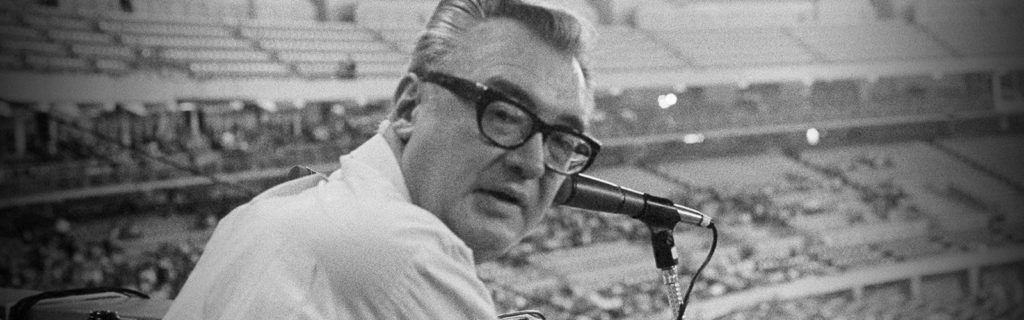

HARRY CARAY: March 1, 1914 – February 18, 1998

I spent most of my youth in Chicago, despite being born in Ohio and descending from generations of Ohioans. Being born in 1970, I was the perfect age to discover baseball right as The Big Red Machine, the dominant Cincinnati Reds teams of the mid-1970s, began to dominate baseball. My parents and grandparents were all baseball fans, and I was hooked. I was a fan of Johnny Bench and Pete Rose. I tried to always wear Johnny Bench’s #5 or Davey Concepcion’s #13 when I picked a Little League uniform. My grandfather eventually retied after selling his company to then-minority owner (now majority owner) Bob Castellini, and we would regularly go to Riverfront Stadium and sit in Castellini’s personal seats, just down he row from Marge Schott and her St. Bernard, Schottsie. I remain a lifelong Cincinnati Reds fan, despite spending of my most 17 formative years in Chicago. Living on the north side of Chicago, it seemed like everyone I knew was a Cubs fan. Even my parents, who were born and raised in Ohio by Reds fans, eventually shifted their allegiance to the Cubs. But I could never get onboard with the Cubs worship. Yes, I appreciated the fact that Wrigley Field was still nestled snugly in an actual neighborhood. And yes, I appreciated the ease of getting to the park on the el. But Cubs fans, on the whole, were annoying. They partied like amateurs, made too much noise, treated the neighborhood they claimed to love like a garbage can, they invaded cool bars like locusts and acted like they owned the place. Most disturbingly, they had a very strange relationship with losing. They seemed to enjoy it. The Big Red Machine (and later the “Nasty Boys”-era Reds of the early ‘90s) had trained me to enjoy winning big. They were dominating teams. Cubs fans seemed to enjoy the cellar, and never seemed to mind the century-plus without a championship. They clung to a weird shabby nobility, girded with nachos and Old Style and trips to the Cubby Bear after. To this day, I don’t understand Cubs fans. But there is one thing about the Cubs that I always loved, and always will. The Cubs had one thing that will always be legendary: Harry Caray.

I’ve often thought that a baseball color commentary announcer would be the greatest job in the world. The play-by-play man calls out the action, and you just get to comment. The color man turns the data into a narrative. And Harry Caray was arguably the greatest color man of all time. Which is odd, because if you really tried to quantify what he did, you could argue that he was terrible at his job. If it was his job to weave a tapestry in between the stats and the emotionless calling of the plays, Harry could be, shall we say, unpredictable. After a few too many beers, his observations could be random, at best. For a period, his observations would include things like tales of area restaurant menus, reminiscences on Cracker Jacks, or the way to pronounce a player’s name backwards. As he grew older, his words would slur more and more, often times aided by the consumption of his beloved Budweiser beer. After he suffered a stroke in 1987, his words became only slightly more slurred even as his schedule relaxed to home games and occasional trips to St. Louis and Milwaukee. Judged solely on what he did, Harry Caray should have been a joke as an announcer. Certainly, comedians like Will Ferrell made career highlights out of mocking some of Harry Caray’s strangest behaviors. But the reality is Harry Caray was quite arguably the greatest baseball announcer of all time. And the reason why is simple: Harry genuinely loved it.

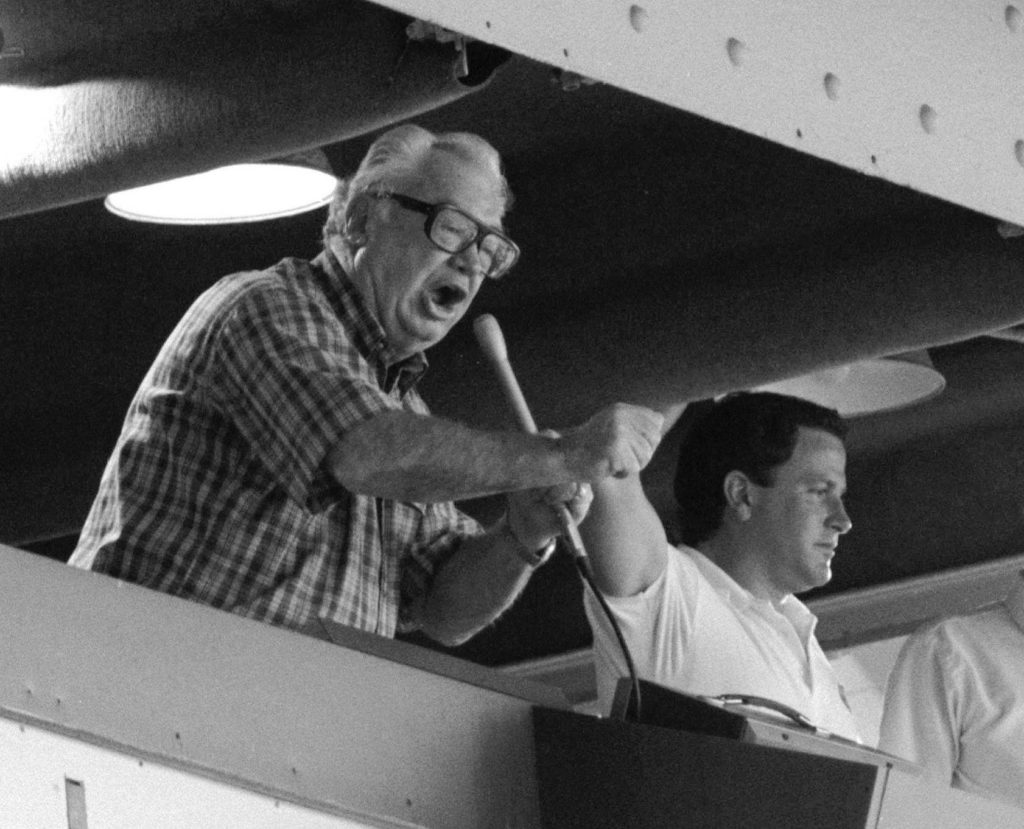

When the executors of Harry Caray’s estate recently cleaned out some files from his office, they discovered Harry Caray’s journal from 1972. The journal was kept for tax purposes, in an era when writing off “entertainment expenses” was common. Harry had just arrived in Chicago as an announcer, and kept track of the nights he went out drinking. As they looked through the book, the executors realized that Harry had gone out bar-hopping 288 nights in a row. And not just for a few drinks. Harry would visit multiple bars every night, racking up $10 tabs at each place – a significant amount of booze on its own in 1972, much less to drink that volume at three or four bars. More interesting was the company he kept during that year. Aside from entertaining every player on the White Sox and most of the Cubs, Harry could be found keeping company with Chicago political and literary luminaries, heavyweight champs, NBA stars… I’ve heard hundreds of stories over the years – first-, second-, and third-hand – from people who had the opportunity to drink with Harry Caray, particularly after he opened his still-popular restaurant in Chicago. Every single story describes Harry as a wonderful raconteur and a great drinking buddy, one who was genuinely interested in everyone. When Chicagoans called Harry “The Mayor of Rush Street”, it was with the deepest measure of affection. Harry was a ruler, but the kind who has a genuine close touch with his constituency. In Harry’s case, they all just happened to live together on the major party street in Chicago.

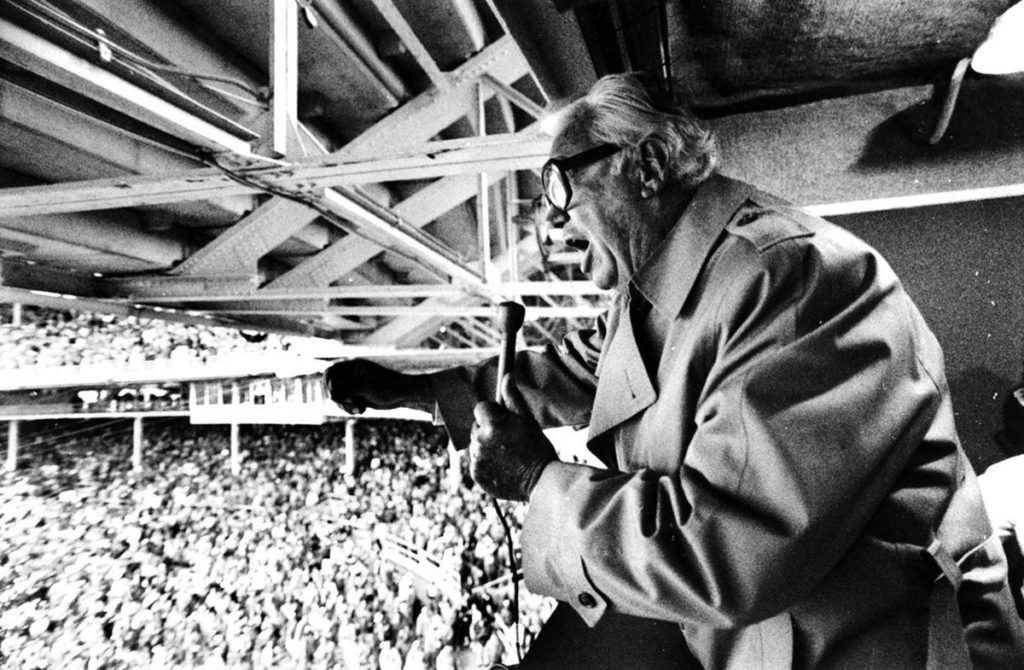

This is not to say that drinking made Harry Caray the greatest baseball announcer ever. Or that his love of people did. Or even his passion for baseball, or his willingness to be a “homer” who openly and unashamedly rooted for his own team. What made Harry Caray the greatest was that he never stopped being passionate about the experience of baseball. Not just the game. Other announcers were far better and more passionate about the game. Other announcers may have tried harder to be more proficient and eloquent announcers, treating their voices as an instrument and their diction as a core competency. And plenty of announcers have been friendly with the area fans. But Harry Caray recognized better than most that baseball is a communal game. It’s a slow game, with plenty of time for communication and “refreshment”. It’s also a generational game, shared in the form of stories and games of catch between children, parents, and grandparents. He was the first announcer to just say “hey” in between pitches to Cubs fans who sent in letters. Harry Caray took a naturally slow game and made it exciting, not just by rooting loudly for the home team and singing raucously during the seventh inning stretch, but also by treating the game of baseball the way fans treat it. He drank, he joked, he said hello, and – most importantly – he sincerely cared about the game: the players, the plays, and the fans alike and equally.

It’s a passion that deserves to be applied to everything. Too often in this “focus on your strengths” culture, we focus on success through our best attributes and forget about the overall experience. We focus on a goal and forget about the people around them. It’s easy to forget about an experience while chasing a goal. That was Harry Caray’s strength. He knew that the story he heard during a conversation at a bar, and the joke he heard in a cab ride to Wrigley, and the friendship with a local reporter, and the love of people – most notably fans of whatever team he was working for – were all threads in the fabric of his career. And he treated each with dignity. Mel Allen or Jack Buck may have done a better job of communicating the action of the ball game, but nobody made you feel like you were hanging out at a ball game as well as Harry Caray. And that’s the point of a baseball game: to go, hang out, have a good time, drink a few beers, share a few stories, and root, root, root for the home team. Harry Caray could have chosen a dozen metrics to prove his worth as an announcer. Instead, he chose to ignore all of the metrics and focus on the experience. And in doing so, became the best announcer in baseball, judged by one metric: the love of the fans.