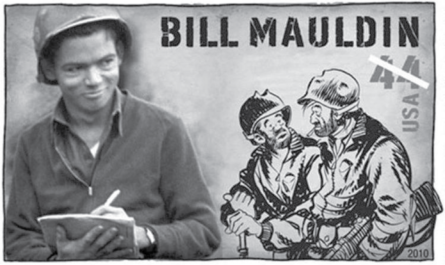

GARTH ENNIS: Born January 16, 197

A friend shared this video from YouTube the other day and sparked an interesting discussion on privacy in the digital age. The creator of the video had taken a series of tweets from the Twitter feed of a woman who had died of brain cancer. She did not know the woman at all, and last I heard, had never heard a word from the dead woman’s family about the video she had made. The discussion my friend had started was mostly a discussion of privacy in the digital age and ethics, namely “Even if we can legally create a video from the public tweets of a stranger, should we?” People argued that just because the woman made a tender, compassionate video, it was still inappropriate for her to have done so. Her picture of the sick woman was an extremely incomplete picture of a person, and was such a limited perspective that it lacked artistic or philosophical merit. I disagreed. In light of this project, my opinion on the matter should be pretty easy to figure out. Any time we analyze someone else’s story and then re-present it, we’re limiting the original story to our perspective. And while it can be dangerous when a storyteller distorts history or performs character assassination by forcing a perspective, the benefits still outweigh the dangers. Offering perspective is an important part of understanding the world around us, and we receive those perspectives from every experience. But some of the best perspectives come from the arts we partake of.

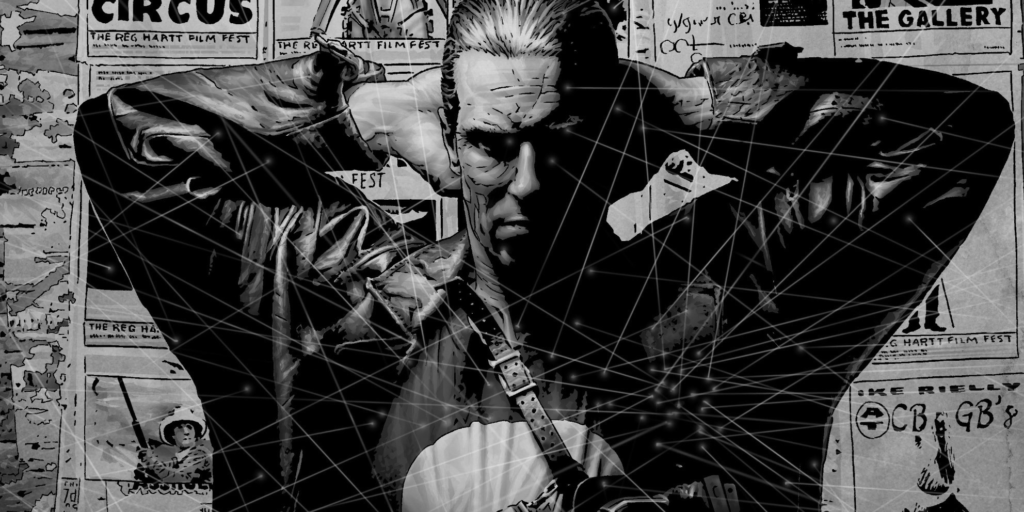

Garth Ennis was raised outside Belfast, Northern Ireland and from a young age was reading comic books. He read war comics and science fiction. But his taste in movies ran towards classic American westerns and war films, and stars like Clint Eastwood and John Wayne. And when Ennis started writing comics, he found that his own voice was not the voice of the shores of Belfast Lough, but a voice with a distinctly American vibe. Comics have historically been a medium that relies on pastiche to help tell its stories. The popular comics of genres rely on tropes that pervade the stories to aid in understanding, and comics writers have borrowed storytelling elements from other mediums for decades. The worst, hackiest comics writers lift an element or two from successful comics and then tweak them slightly. The best comics writers are like the best pastiches, and they pull references from numerous media and create something not only interesting, but insightful. Ennis’ early works were ambitious but limited. The ideas were direct and confrontational. The ideas were Ennis’, but they were only Ennis’ and they were done to provoke a specific response. It wasn’t until he began writing Judge Dredd in 1990 that the idea of pastiche began to work itself into Ennis’ voice. (Significantly, one of the villains he created in Judge Dredd was named “Muzak Killer”, a serial murderer who made decisions based on his musical aesthetic and who found originality and importance to be the most important factors in deciding the worth of a life.) Soon, Ennis was writing Hellblazer, a decidedly English comic series, but Ennis continued to influence the writing of the work with references and influences from other media.

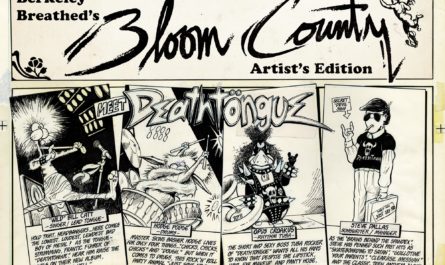

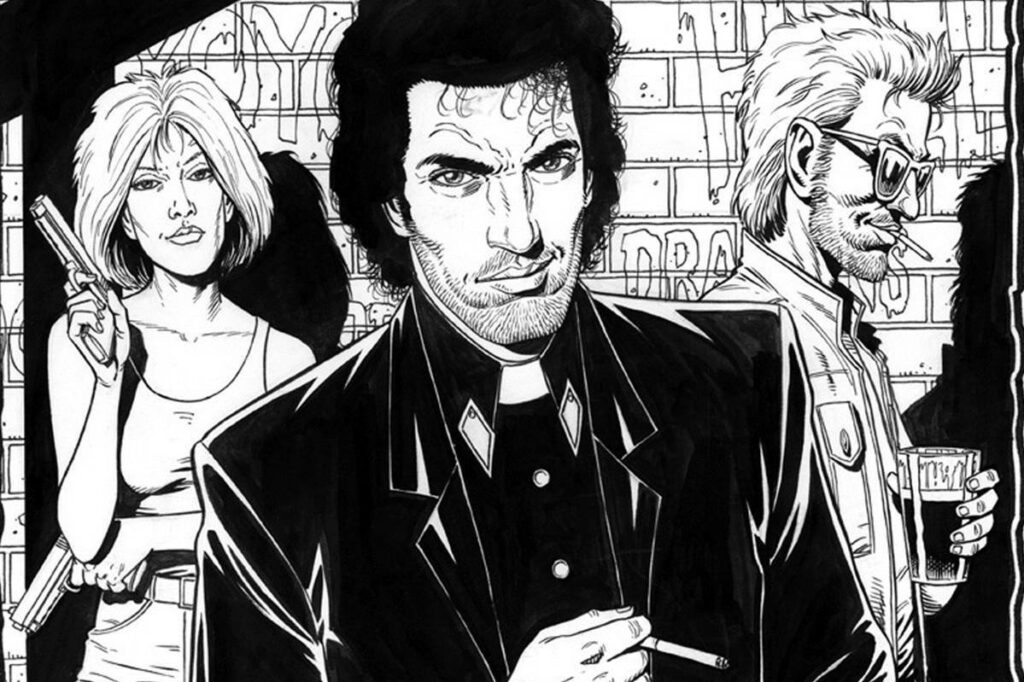

In 1995, Ennis began the seminal work of his career, the 66-issue series Preacher. Preacher was as close to a Tarantino film as comics had seen. There were so many references to other works that part of the enjoyment was in decoding the references. If you could identify them, you entered a rabbit hole of depth to the character or to the story. If you couldn’t (or didn’t even notice the reference), you still benefited from its applicability. And the references came from everywhere: comics, music, movies, poetry, stand-up comedy. As Preacher built its cult following, Ennis continued to write series after series: The Demon, Hitman, Bloody Mary, The Darkness, Shadowman. Ennis continued to connect with audiences, referencing everything applicable to the stories he was trying to tell.

The argument against Ennis’ work was the same argument that I was hearing about the YouTube video. Ennis created a world that showed a very dark side of American and British machismo. Americans were not just Americans, but they were the ugliest of “ugly Americans”: insanely violent hillbillies, psychopaths, narcissists, serial violent offenders. Ennis’ male characters were either hyper-masculine or – if not physically imposing – they controlled everyone through clever cunning and sociopathy. His lead female characters were simply masculine archetypes with stripper bodies. Other female characters were either efficient servants of strong men or whores. And background characters of either gender were usually dumb and brutish characters to either fill the composition of the frame or be mowed down by the narrative. The perspective Ennis chose to depict was limited and horrible… but recognizable. These were people we knew and characters we grew up on, turned into comic superheros. The most interesting part was that – as terrible as these characters were – we loved them. Ennis was (and remains) one of comic most popular writers. His characters are memorable in part because we already knew them, and in part because he writes such entertaining stories. But more importantly, the perspective Ennis chooses is honest. The violence of his characters may be overblown, but at the same time, they shed a light on the violence within our culture. The wealthy sociopaths who control society for their own benefit may be cartoonish, but not that far removed from Donald Trump or the Koch brothers. The secret agencies that secretly watch over the world may seem silly, but less so in the age of NSA spying. Ennis may be forcing a perspective on us, but it’s an honest perspective, not a hatchet job. And through his honesty, we recognize it. And acknowledge it as a part of ourselves. Horrifying as Ennis’s characters may be, we’re actually able to relate to them because they spoke to something we had seen before, either in real life or in the media, and we could understand them. We’d already formed an opinion on them before Ennis had even written them.

When creating a story, we can’t help but create a limited perspective. Even the artists most obsessed with the idea of creating an environment of complete truth are limited by time – something has to be left out of the story. What the artist chooses to whittle away creates a perspective, whether the artist likes it or not. But shy of lies or outright character assassination, perspective can be insightful. Because people are complicated. Our stories are not limited in perspective. Every decision we make and every belief we hold is the result of potentially hundreds or thousands of previous inputs. Top duplicate that would be impossible. But when we take in the limited perspective of an artistic influence, we are able to incorporate that into the complex series of connections that make up our lives. We take simplicity of limited perspective and make it personal and complex. This is the nature of art. But isn’t it the nature of human interaction, as well? Isn’t it what we do when we create stories for strangers we see in public? Isn’t it what we already do with co-workers and community members and people we know in a limited capacity? We tell ourselves what we need to know about these people, and we incorporate their actions into our complex lives. Nobody questions our right to do that. Because in those moments, we’re (hopefully) being as honest as we can to the story, and to our own lives.

When creating a narrative, it is our responsibility to be as honest as possible. Acknowledge that we have a limited perspective, but that perspective – when examined against the complexity of the lives and the depth of the character of those who will hear the story – could still yield some important insight. These stories have the potential to broaden our view of the world. We just need to be honest. If we’re honest, even the worst monsters become relatable. If we’re honest telling the stories that surround us, everything and everyone can become a part of us.