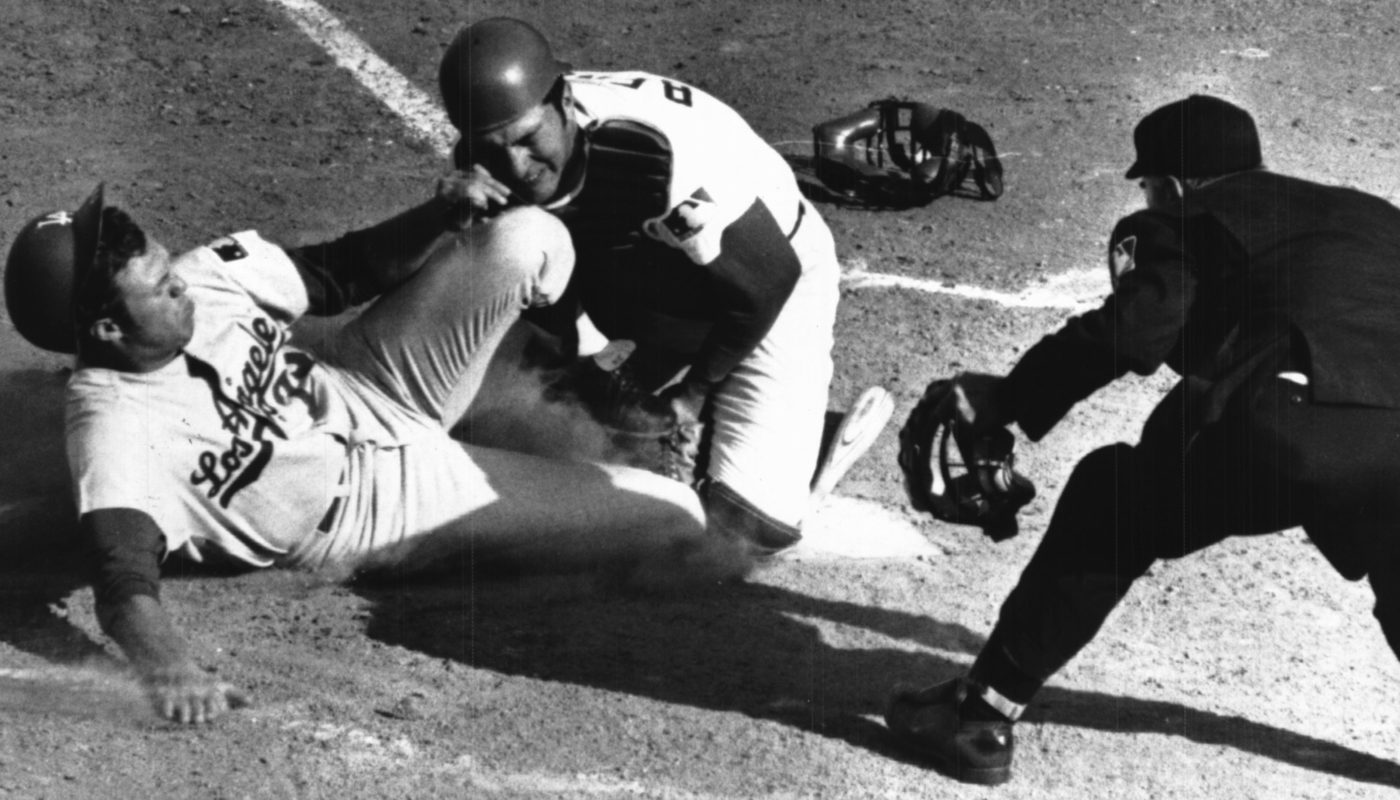

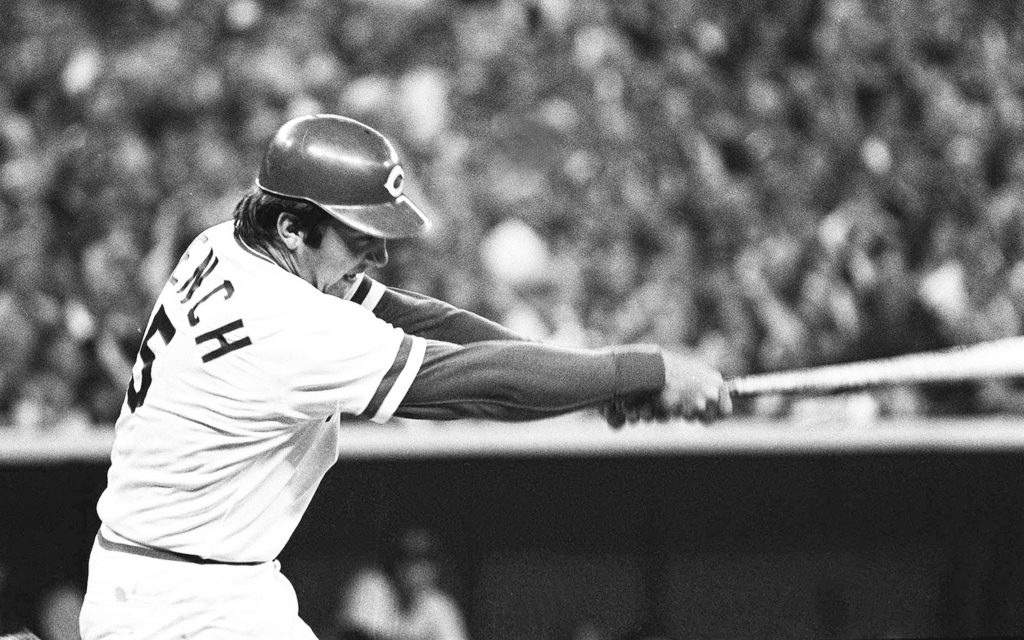

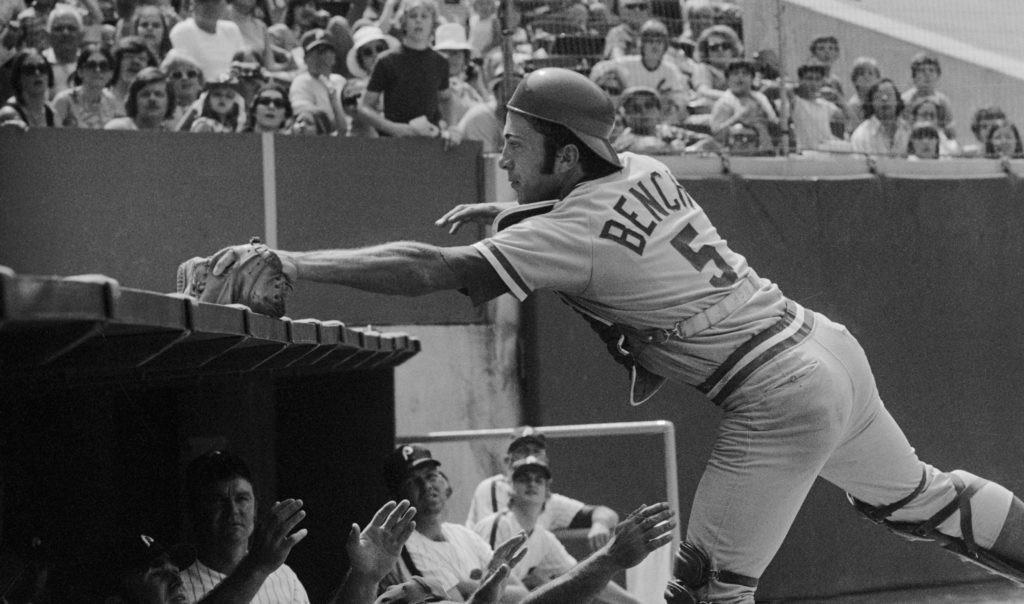

JOHNNY BENCH: Final game of his professional baseball career – September 29, 1983

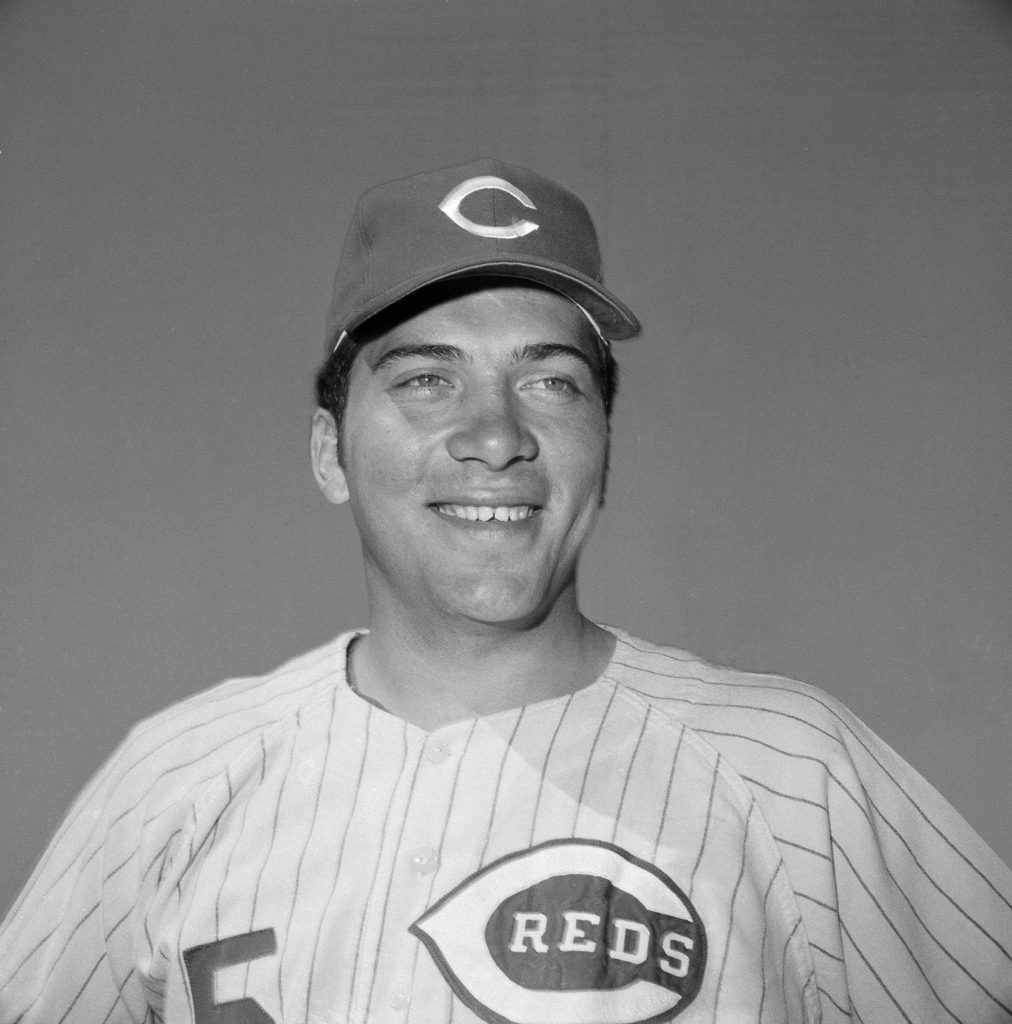

My wife and I were recently discussing the process of writing. I stopped writing a number of years ago and worked hard to keep myself from having the kind of opinions and thoughts and feelings from which writing naturally springs. As I’ve tried to re-engage with writing, I’ve been plagued with stops and starts rooted in a profound lack of self-confidence and a general uncertainty that my thoughts had an merit. I complained to my wife that more often than not, the words I wanted to write weren’t flowing naturally out of me, but required me to force them out. Instead of being my own voice supporting my own thoughts, they became a hybrid of borrowed opinions and style imitations. It was wholly unsatisfying. I fear that I’ve “missed my window” and become too old and complacent to every write or create again. That kind of self-doubt is self-perpetuating, and I’ve found myself spinning emotionally, while I produce very little. And so I began to look to authors I admired for inspiration on how to overcome that kind of hurdle. Given the nature of this project, it should come as no surprise that I have a deep pool of inspiration to choose from. I read as much as I could, and then as I sat down to write tonight, inspiration came from an unusual place: Johnny Bench. Team captain for “The Big Red Machine” of the 1970s – one of the greatest teams in baseball history. Johnny Bench was the catcher, the leader, “The Little General”, and my very first hero.

I come from a long line of Cincinnati Reds fans, on both my father’s and my mother’s side. When I was an infant, my grandparents bought me a dinner plate with Johnny Bench’s face on it, and a hero was born. I adored Johnny Bench. I grew up with his posters on my bedroom wall. I wrote reports about him in school. I watched The Baseball Bunch regularly, owned the “Johnny Bench Batter-Up!” hitting aid, and wore number 5 whenever I could in Little League. So I was crushed when Bench announced his retirement early in the 1983 season. He’d played 16 seasons, been to 13 All-Star games, hit over 350 home runs, won two World Series and ten Golden Gloves. There wasn’t much left for him to do. More importantly, he’d spent the previous two seasons as a utility infielder. He was in his mid-thirties and his knees had started to go, and the catcher who used to scoop up wild pitches using just his bare hands fire a throw to second base had lost a few steps over the years. Certainly, he could have continued playing behind the plate until his final game. Many catchers do. But the thing about great performers is that they know better than anyone else when they’re no longer able to perform to their own standards. They may still be good – great, even – but what appears to be just a slight degradation to those of us on the outside is a traumatic loss to the person experiencing the fading of their skills. So Johnny Bench’s retirement shouldn’t have come as a shock, but it made me sad. I’d never lived in a world without Johnny Bench as a Red, and I didn’t welcome the change.

As the season worked its way through the summer, I watched every Cubs-Reds game and meticulously kept score, so that I could someday go back and relive the games in my head. Sadly, by mid-summer Johnny Bench was rarely playing. He’d come out late in the game to pinch-hit for a pitcher, receive a rousing applause from the stands, and return to the dugout. Despite the random and infrequent appearances, I watched the games and waited to see him. When my family went to Ohio to visit family in late July, I was more excited. My grandmother listened to the Reds games religiously on the radio as she tended to the house, and away games were usually televised. The Reds were on the road at that time, so I prepared a small stack of homemade scorecards. I would watch the West coast games with my grandfather in his den. One night, the Reds were in a tight game with the Los Angeles Dodgers. The game was nearing the end with no appearance by Johnny Bench. But as the Reds took the field in the bottom of the 8th, the announcers went wild. Out of the dugout came The Little General, dressed in his catcher’s gear. He’d caught fewer than ten games in the previous two seasons, and yet here he was. The fans at Dodger Stadium had stuck around with the hope of seeing him bat one last time; I remember the stadium going wild. It was as if the phone booth doors had opened and Superman had stepped out. People cheered for their chance to bear witness to greatness one final time. Johnny Bench had blessed us with one final appearance behind the plate, and the crowd was thrilled. Of all of the memories I have from all of the baseball games I’ve seen in my life, few are as sharp as the memory of my grandfather’s laughter when Bench stepped out of the dugout in his catcher’s gear. It wasn’t my grandpa’s typical jovial laugh, the way he’d laugh at a joke. It was a deep belly laugh, filled with gratitude and joy. It was the kind of laugh you hear in war movies when the cavalry would arrive at the last moment to aid the nearly-beaten hero. Not rueful or spiteful; it was a laugh that said “Finally. Everything’s gonna be alright.” And so it was… for ten seconds. Rick Monday, another player at the end of a long career, hit the first pitch thrown to him and easily reached first base. And the Dodgers replaced Monday with a pinch runner named Derrel Thomas, a utility outfielder who spent most of his time as a pinch-runner because he was reportedly the fastest man in Major League Baseball.

Professional sports is competitive. That competition is a survival game, and it can be downright cruel. When pitcher Monte Stratton lost his leg in a hunting accident, batters would bunt on him. Batters would hit lines drives at one-armed pitcher Jim Abbott with the hopes that he didn’t have his glove on correctly. It’s an unfortunate by-product of the game. So it was only natural that the Dodgers would exploit the appearance of a formerly-fierce catcher who’d slowed a step or two over the years. On the first pitch, Thomas broke for second and unleashed the Johnny Bench of 1976. Bench popped up as nimbly as he had in his early twenties, threw every bit as quickly as he ever had, and landed a perfect throw a few inches above the ground on the inside of second base, where it landed in Dave Concepcion’s glove well before Thomas had neared the bag. It wasn’t just a textbook play; it was god-damned glorious.

That the Reds ended up losing the game was irrelevant. What stuck with me over twenty years was not simply a great play by a legend who was rapidly passing his prime. What stuck with me was the reaction to the play: mine, my grandpa’s, the announcers’, the fans at Dodger Stadium’s. It was a celebration not rooted in demise. Whether we knew it or not, we weren’t rooting for a reminder of what had been, we were celebrating what still was. Talent and skill, in whatever form, are gifts that can erode for a million different reasons. But that brief moment was a reminder that if we do choose to engage that talent, a half-assed attempt simply isn’t worth it. A lazy throw to second at that moment would have yielded nothing but nostalgia and longing. Sure, the audience would have been appreciative of seeing Johnny Bench behind the plate, but there’s no lesson there. No inspiration. It’s reminiscence, and few things are as limiting as thoughts that disfavorably compare our present existence with a fond “remember back when…”. And for three years, I’m certain Johnny Bench heard that narrative play out over and over in his head. His joints were too weak and old. His knees were too shredded. His arm was too slow. He could still swing a bat, but not much beyond that. But then, in one magical moment, he gave himself permission to ignore that narrative and throw himself into his work with reckless abandon.

When we’re not prepared to do something, or we’re not in a place to perform to our own standards, it can be frustrating. Quitting can feel like the best option. Or the only option. But in the midst of that spiral, if we’re lucky enough to believe that we might be able to perform to our own standards – even if only for a minute – we owe it to ourselves to honor that thinking. And when we crouch down to get to work, we need to be prepared to give it everything we can. Because whether we ultimately succeed or fail, to give everything we have to give in pursuit of that moment is rare and glorious. And we all owe the world that much.