MICHAEL O’DONOGHUE: January 5, 1940 – November 8, 1994

Years ago, I went with my grandmother to a funeral of one of her siblings. My grandma’s family was not the most emotionally demonstrative. They were loving and caring and definitely fun to be around, but they weren’t known for touching or hugging. All of my grandmother’s siblings would frequently perform the “Irish Good-bye” (leaving without saying goodbye or announcing your departure) at family gatherings. Accordingly, funerals were generally non-demonstrative. Everyone was sad, certainly, but for the most part, composures were kept and the event was always low-key and dignified. At this particular funeral, however, those paying their respects were set up to pass the open casket on the way in, during the service, and as they left. This kind of overt tugging of the heartstrings (not to mention the resulting tears and sobs) upset my grandmother, and she walked out of the room through a side door. We made our way into the hallway, and my grandmother joked, “Maybe they could just mount and stuff him and hang him on the wall, then we could all stand and stare at him any time we wanted.” It was a disturbing joke, unless you knew my grandmother. My grandmother was funny on any given day, but she had a particular gift for making jokes at difficult moments. Jokes which – somehow – made everything better. Because one of humor’s gifts is to lessen tension, even when lessening that tension comes at an inappropriate time or place. Yet there are plenty of people – hilarious people – who have mastered this technique.

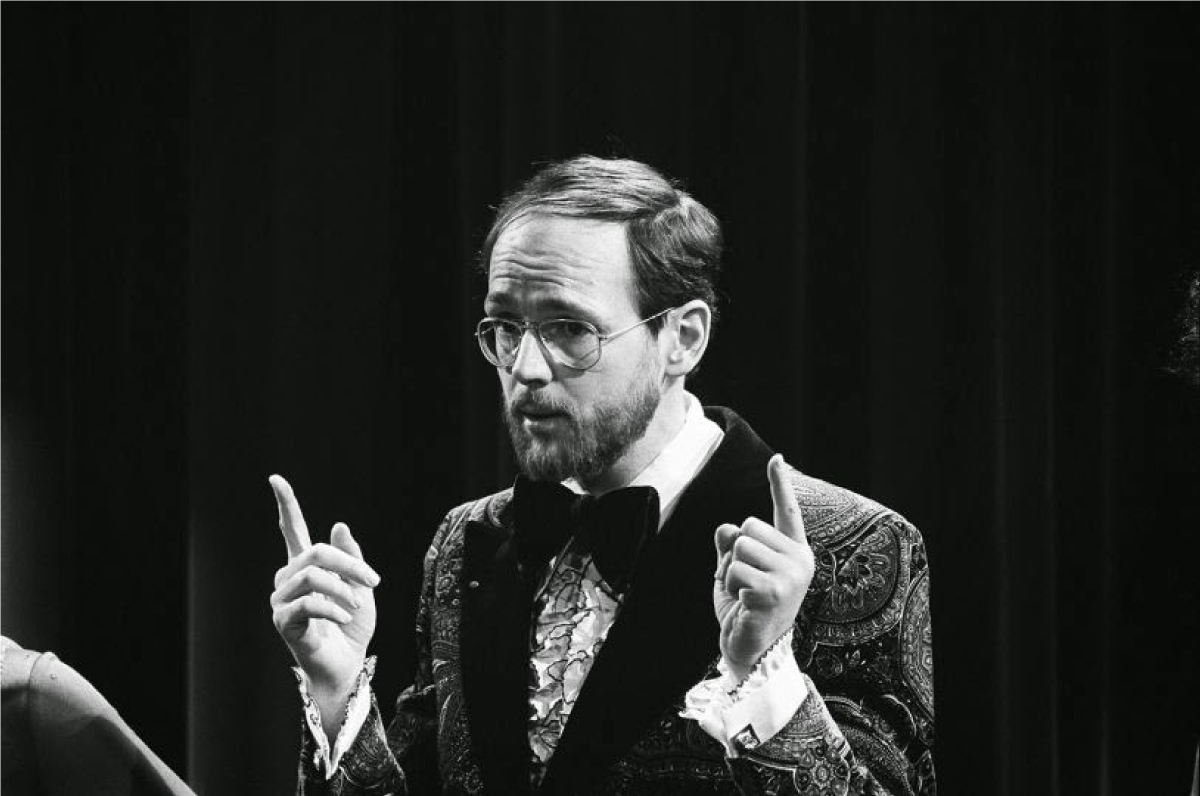

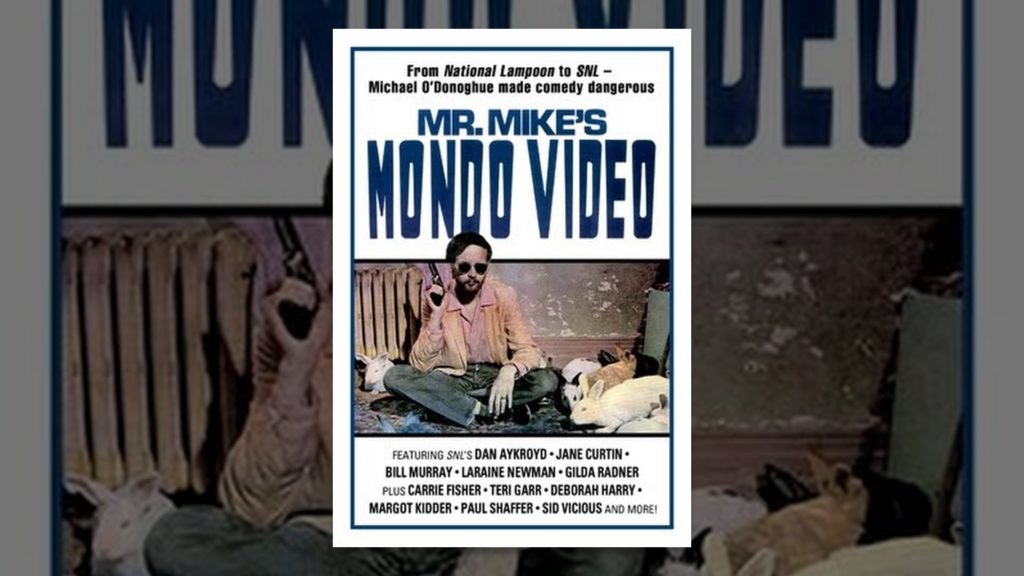

When legendary National Lampoon and Saturday Night Live writer Michael O’Donoghue died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1994, the explosion within his brain seemed appropriate to those who’d worked with him. O’Donoghue had a brutal reputation for violent temper tantrums. He would rage and scream when confronted or edited. He would throw telephones at walls, through windows, and at co-workers. He began using a walking stick just so he could swing it like a bat during his tantrums. As large a shadow as O’Donoghue’s hysterical temperament cast among comedy writers, the genius of his comedy writing loomed larger. O’Donoghue’s earliest work was an erotic satire of adventure comics, published in serial form in 1965 in Evergreen Review. The comic was so deadpan hilarious, it remains one of Garry Trudeau’s (creator of Doonesbury and the first comic strip artist to win a Pulitzer) biggest inspirations. Soon after, O’Donoghue was recruited to help found National Lampoon magazine and helped set the comedic tone for the magazine. Instead of simply satirizing with a deadpan tone, however, O’Donoghue’s tone became confrontational. And dark. It was a transition that would only continue to grow throughout his tenure at National Lampoon, and later with Saturday Night Live.

I’m sure I stole the line from somewhere, but I’ve always said that “comedy is the voice of outrage”. I believe that almost all comedy is rooted in a dissatisfaction with the absurdity of the world. It doesn’t matter if the topic is airline food or socks disappearing in the laundry or napalming infants in the Viet Nam War, it’s all rooted in outrage. When comedians tell a joke, they’re not merely crafting something according to a set of techniques and guidelines, the way a song can have meaningless lyrics and very basic chord structures but still be a song. A joke can’t exist without being confrontational. Even a joke as old as “Why did the chicken cross the road?” is confrontational. It confronts our expectations about how we should answer questions when they’re asked, and how we prepare our mind for jokes. The literal answer to the question is outrageous, given the context. Confrontation and outrage that lack humor are polemics; but there is no humor that lacks confrontation and outrage. Sometimes the outrage precedes the confrontation (“What’s the deal with college football fans?”), and sometimes the confrontation leads to the outrage (puns, “Why do firemen wear red suspenders?”). But comedy needs these components, and while all comedians seem aware of it, some actually choose to embrace it.

When O’Donoghue wrote “The Vietnamese Baby Book” for National Lampoon he meticulously satirized the Baby Boom America obsession with documenting the first months of our children’s lives by creating a baby book for an infant in war-torn Viet Nam. The book detailed all of the baby’s scars and injuries. (“Baby’s first word: ‘medic’.”) Forty years after its publication, it remains a brutal, dark piece of satire. But more importantly, it’s funny. Yes, it’s a guilt-inducing funny, but funny nonetheless. And it had to be. It had to be because the pro-war side of the argument refused to see a negative to the war in Viet Nam, and accepted collateral damage as a necessary evil. And the anti-war side of the argument was accused of emotional baiting by mentioning collateral damage. And nobody was voicing an opinion defending the people of Viet Nam. And there were no domestic casualties. So we argued our opinions, gave birth to our children (me included), and proudly documented their early years of pictures and first meals and first steps and first words. It was not a time for dialog, it was a time for confrontation. But the protests of the era weren’t confrontation, and they weren’t dialog. Outraged by the stagnant (yet loud) politics of the era, O’Donoghue made it impossible to support the war without acknowledging the horrors of collateral damage. He made it impossible to oppose the war without acknowledging the imbalance of sacrifice between a foreign war and a domestic war. And he made it impossible to not notice how vacuous it was to document the lives of our children as we supported – either implicitly or explicitly – the bombing of someone else’s child. Yelling about it would have been drowned out. But by making people laugh about it first, they had to consider the realities underneath their laughter.

When my grandmother died, I described her in the eulogy as “brave”, which was an odd word, because she regularly described herself as “a chicken”. And that was true. She was afraid of a lot of tangible, physical objects: mice, escalators, heights, the tide. But the bravery she exuded was in that same vein as Michael O’Donoghue, with a willingness to channel her outrage into something funny so that others could understand her position. So that others could extract themselves from a fixed position and confront their fears, their hypocrisies, their flawed logic. My grandmother was funny, which was a gift. But she used that gift – as all great comedians do, and as Michael O’Donoghue did – to help us see the world in a different way. Outrageous humor helps us cut through our personal outrage and consider it.

One of Michael O’Donoghue’s most famous skits on Saturday Night Live, he did an imitation of Vegas singer Tony Orlando… if he had fifteen inch, razor-sharp needles plunged into his eyeballs. O’Donoghue shimmied to Vegas lounge music for a few seconds, then fell to the stage, screaming and writhing in violent terror.

Confrontation. Outrage. Shock. Screaming. In the right hands, it leads to realization, wisdom, and forgiveness.