BOB NEWHART: Received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, January 6, 1999

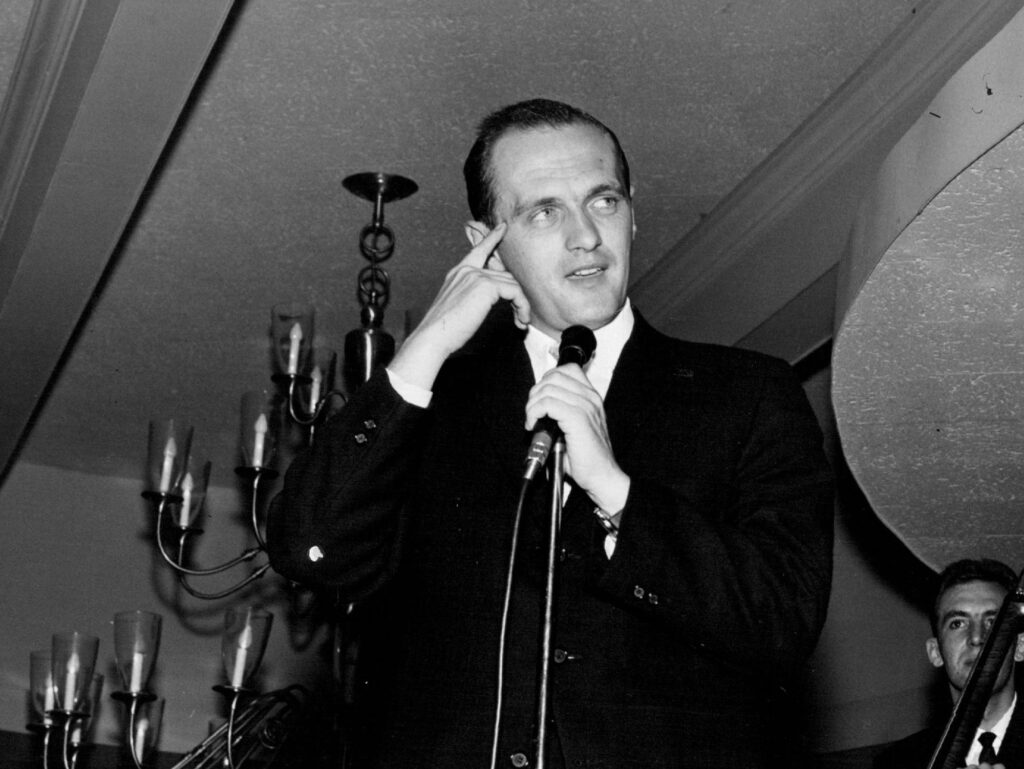

I don’t remember a world without Bob Newhart. The Bob Newhart Show premiered in 1972, and by most accounts, lingered in the Top 15-20 shows for the majority of its run. While never a massive hit, it had a cult following strong enough to convince Newhart to continue the show when the ratings slipped low enough that it was no longer enjoyable to make. My parents were among those fans who watched the show regularly, and being a typical ’70s family with one TV, I watched what my parents watched. What we were seeing then (and what the ratings reflected) was a new kind of comedy, and one that didn’t necessarily conform to typical comedy standards, which made it both irresistible to some and less-accessible to others. But it changed the world, nonetheless. Years later, as an adult, I had a professor who lived in an apartment on Chicago’s north side. After a post-class coffee and discussion one day, I drove him home. As we pulled into the circular drive in front of his building, he pointed across the street at the apartment building. “Bob Newhart Show,” he said. And so it was – the exterior of Bob and Emily’s apartment. The show had been off the air for 20 years, but somehow, he was certain I would know what he was talking about. That was the impact of Bob Newhart.

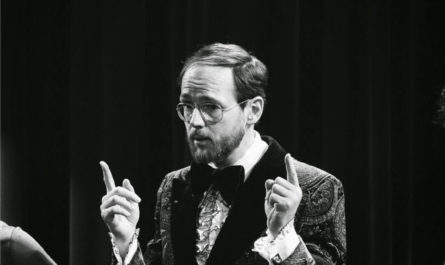

Some people are thrust into the spotlight and you know instantly that they’re going to change the world. From the first notes of Elvis’ earliest appearances on the radio, it was clear he was going to change music forever. When Jackson Pollock premiered “Mural” in 1943 it was clear he was going to change the art world. But this wasn’t the case with Bob Newhart. In the mid-1950’s, Newhart was an accountant in Chicago. Quiet and polite with a small frame and a high hairline, he was the last person to ever “burst onto” a scene. And yet, he did. When his first album, The Button-Down Mind of Bob Newhart was released in 1960, it went to number 1 for 14 weeks, an impressive achievement for a comedy album. More importantly, it was impressive because it was different from any comedy album that had been released before. Newhart had created a series of comedy routines where he would speak to someone on an imaginary telephone. As the bit would progress, he would try to handle increasingly more-ridiculous requests from the other end of the phone.

The “telephone” bit was far from new in comedy. It had already become a popular premise in Chicago. Legendary Chicago comedian Shelly Berman had a well-known telephone bit. Mike Nichols and Elaine May had numerous two-person telephone bits. But Berman and Nichols responded to the insanity with a studied, theatrical response. They attempted to keep a lid on the insanity and not lose their cool. Newhart, on the other hand, responded in the way that only a staff accountant for a giant corporation could respond; he nebbishly agreed with the craziness and tried to change his own reasonable outlook to make sense of it. The power of the telephone bit is that it requires the audience to fill in the blanks. We hear Newhart’s shocked response and then we backtrack to figure out what crazy thing was said on the other end of the phone. And the depth of the craziness is entirely on us. It’s a brave position to take as a comedian, because you’re asking the audience to create the punchline. It’s part of the reason the telephone bit had never taken off before Newhart.

What made Newhart different was in his “typical corporate drone” responses. If the premise of improv is to always agree with the scene and then add to it (“Yes, And…”), then corporate America takes that premise up a notch. And it does it in the real world, regularly. Bob Newhart’s act was all of our lives, writ hilarious. His longtime best friend Don Rickles referred to Newhart as “Charlie Everybody”. Not even “Everyman”, which might give him an air of literary significance, but “Everybody”. Newhart tapped into every powerless discussion any of us has ever had with a buffoonish superior, and he allowed us to make it personal. He allowed us to put in our own punchlines, specific to us. It was his gift as a performer. He would take it into his television career, as well. The dialog of both The Bob Newhart Show and Newhart was peppered with jokes that required the viewer’s imagination to add the humor. “Bob hasn’t been in a bad mood since last summer when he sat on that bee,” Emily said in one episode. The entire joke balanced on the viewer’s willingness to not only imagine Bob Newhart being stung on the butt by a bee, but to imagine his outrage. The outrage and imagery would be different for every viewer, but all of us would make it funny.

If there are two reasons Bob Newhart is beloved, it is because he understands who we are as an audience, and he trusts us to finish his jokes for him. He trusts that we will not only make them personal, we’ll make them funny, as well. I read a study recently that showed how agreeing with other people will make you more trustworthy in their eyes. In other words, the more I entrust you with making decisions, the more you find me worthy of your trust. That was the dynamic we share with Bob Newhart. Newhart spent his entire career trusting us with his comedy, and we love him for it.