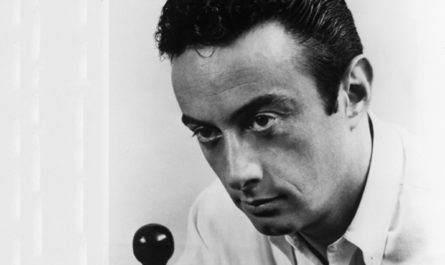

SAM KINISON: December 8, 1953 – April 10, 1992

It’s never easy to admit you’re a fan of Sam Kinison. Even at the peak of his popularity, the admission that you found him funny was always met with an argument. And any attempt to define what was so amazing about Kinison was abruptly cut short with the (justified, accurate) criticisms against his misogyny and homophobia. And there is no defending the misogyny and homophobia. Watching Kinison’s “political” humor today is downright anachronistic; he feels as distant and uninformed and unenlightened as some of the social fright documentaries of the 1950s that tried to scare kids about venereal disease and marijuana. It’s painful stuff to watch, not just because the words are so stupid, but because it’s difficult to see stupid words delivered so masterfully. And that was Kinison’s gift and his curse. If we can ignore the words he said, and instead examine how he said them, we can get a glimpse of true genius. (His curse was that he was too entertaining and mesmerizing to simply ignore, and ended up polarizing people over his content, which was the weakest part of Sam’s comedy.) But given the one-way nature of this platform, I’ll use the opportunity to explain something I tend to keep hidden – why Sam Kinison deserves some respect.

If you ask anyone what they remember about Kinison, nearly everyone will say, “The screaming.” People have tried for years to put the right poetic punch on Kinison’s scream, describing it as creatively as they could. Because Kinison’s scream definitely packed a punch. But Bobcat Golthwait screamed, yet his act was entirely different from Sam’s. Both were primal and generally unexpected, but Bobcat’s screams punctuated his humor. They were the interstitials; the frustrated screech of a man whose brain was too jammed up to organize anything properly. With Kinison, the scream carried the punch line. It became as much a part of the humor as the punch line itself, and neither could stand alone.

Comedic timing and theatrical timing have one very common similarity. The best comedians and actors are expressive enough that they actually foreshadow themselves. Their words and expressions are so open and emotionally aware that the audience connects with them, and begins to know where the actor is going. So when the actor arrives at a critical moment, the audience has already arrived there a fraction of a second before. Acting (and comedy) then become a process of emotional reveals which the audience feels connected to, because they’re not simply being entertained, they’re being validated. Years ago, I read an article about leadership which claimed that the best leaders knew that they could not force people to go somewhere they did not want to go, and that the best leaders can only lead people down the path they want to go down. The quote was, “The best leaders follow, from a step ahead.” The quote is perfect for actors and comedians. The best comedians have you anticipating the punchline before they arrive at it.

That ability to lead an audience was Kinison’s greatest strength, as well. What made Kinison so unique, however, was that once we reached that moment of recognition and prepared ourselves for validation, Sam would explode. The place we arrived would still find validation. The words Kinison spoke were the words we expected, but delivered in screams and wild motions. Kinison was like opening the closet door to grab your coat from the hanger, but finding a chained jaguar in the closet with it. The coat is still there, as expected. But there’s something more exciting and dangerous with it. And then, as soon as we’ve recovered from the excitement and shock, Sam would return to calmly setting up the next joke. Barley moving. His tone completely regulated. Guiding us to where we know the punchline is, but aware that something wild awaits us, as well.

A lot has been made of Sam’s early career as a minister. The focus has primarily been on the dramatic fall from “man of God” to “outrageous hedonist”. But twenty years after numerous evangelical empires crumbled under the weight of human fallibility, it’s no longer surprising that ministers can be corrupted. (It was no shock that Sam ended up in a relationship with Jessica Hahn, the woman at the center of the Jim Bakker scandal.) The part that seems to be overlooked is the influence Sam’s evangelical training had on his performance. Ministers, particularly Pentecostal ministers like Sam was, have long used that style to drive a point home. They make people aware of sin and its punishment, and then drive the point home loudly and expressively. That Sam was able to use that style as a tool to make people laugh was impressive, but should come as no surprise to anyone.

Admitting you’re a fan of Sam Kinison is never easy. But in reality, what I admire about Sam is that ability to communicate like a leader – taking people where they want to go, but doing it from a step ahead. It’s a lesson we all could benefit from. So much of life is trying to wrangle conversations to our way of thinking, or ignoring the other person while we wait to control the direction of the conversation. Too often, we twist dialogues to be only about us and our needs when truly, the most effective communicators allow the conversation to go where it needs to go; they just stay a step ahead of it. It’s strange to think that the lesson I learned from Sam Kinison was one of empathy and understanding, but it’s true. Engaging with people through patience and active listening and allowing things to unfold as they will will earn you trust and respect. It will not only allow you to speak your mind, people will welcome it, and feel connected to it. And once you have that, you can even scream, if you want.