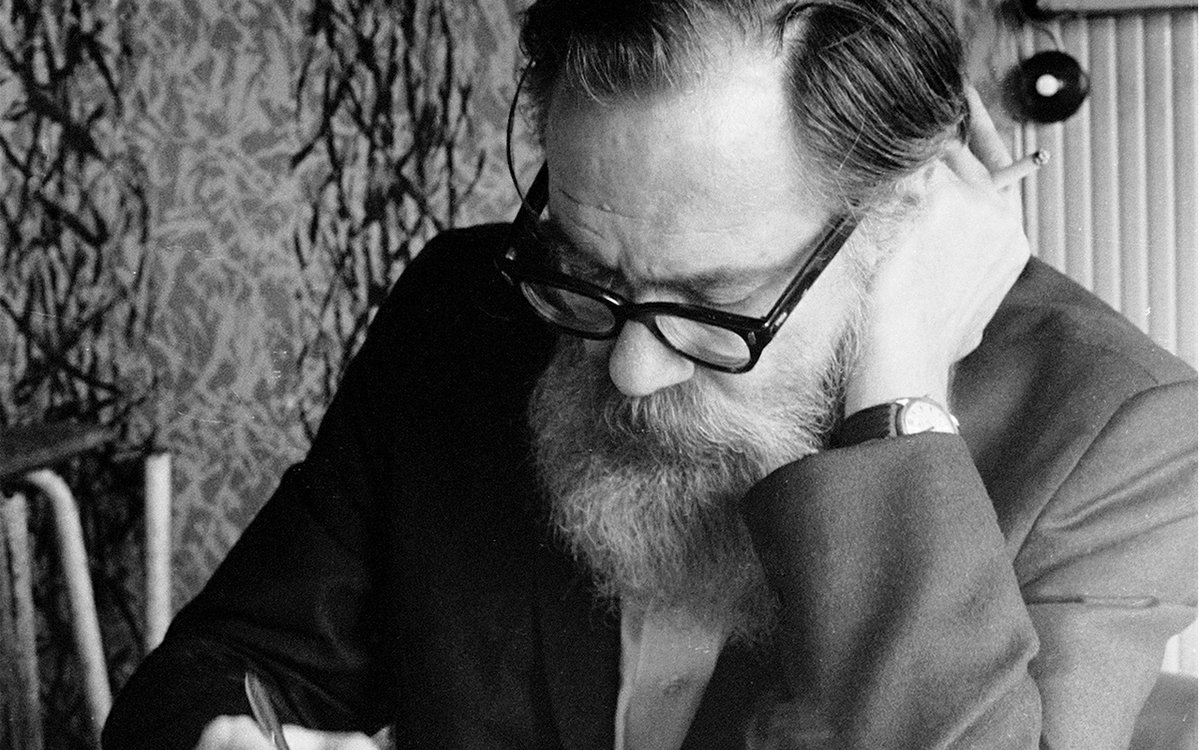

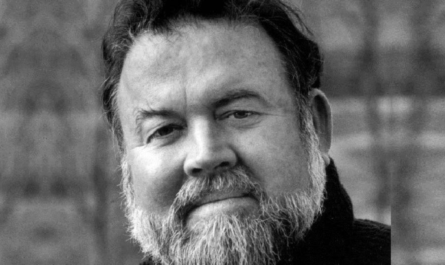

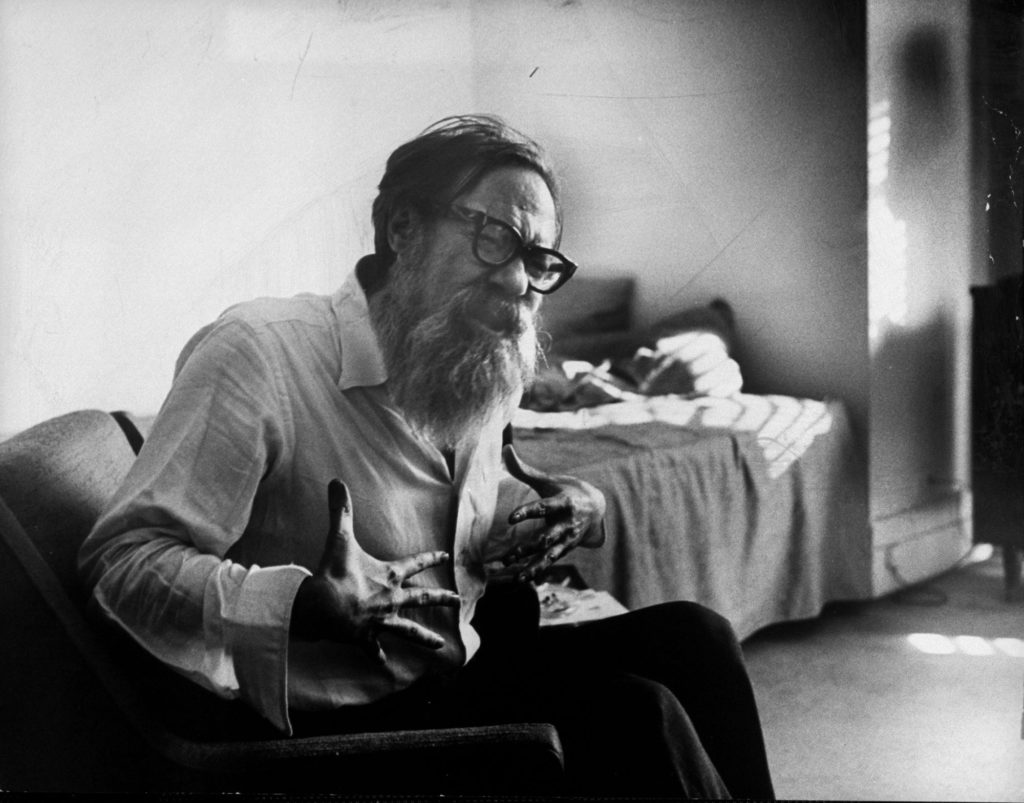

JOHN BERRYMAN: October 25, 1914 – January 7, 1972

When I was a young man infatuated with poetry, I read the poets whose lives I most wanted to emulate. I sought out contemporary American poets with reputations for iconoclasm. Angry young men don’t generally enjoy the company of their own kind, but they live for a good example to follow. And so I devoured the works of poets whose work spoke to me. The Beats. Amiri Baraka. Diane diPrima. Whitman. Kathy Acker. Dennis Cooper. Jim Carroll. Jimmy Baca. A long line of literary brilliance with common traits of alcoholism, addiction, poverty, depression, and suicide. I was 22 when I got my first hosting gig – Monday nights at The Bop Shop in Chicago’s (then very-pre-gentrified) Wicker Park, one of Chicago’s neighborhoods with the richest literary history. One night, a friend of mine in his 40s recommended the poetry of John Berryman.

“You’ll like him,” he offered. “Amazing writer. Got a million influences and borrows from tons of styles. Plus, he was an alcoholic and eventually killed himself.”

Right up my alley.

And so I checked out The Dream Songs, Berryman’s most famous collection of 77 poems which create an epic story of the life of their narrator, Henry. I remember reading the work, but the work fell so flat with me that I didn’t retain any of the work. What I did retain, however, was a small point I read in an article about Berryman’s suicide. On January 7, 1972 Berryman jumped from the Washington Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis and killed himself. The point that struck me? As he jumped from the bridge into the icy waters below, Berryman waved goodbye.

I could never understand why that fact stuck with me all these years. It wasn’t just the cinematic nature of the act; in fact, I never viewed the act as dramatic or showmanlike (the way Oscar Wilde’s alleged final words – “either these curtains go, or I do” – were). The act was haunting. And made more haunting by the fact that I didn’t seem to connect with his work. On paper, Berryman’s poetic legacy – not to mention his “doomed poet” dysfunctions – should have made me into a fan. But I could never connect with the work, and by my late twenties, I had stopped reading and writing poetry, and certainly had stopped trying to understand my reluctance to enjoy Berryman’s poetry.

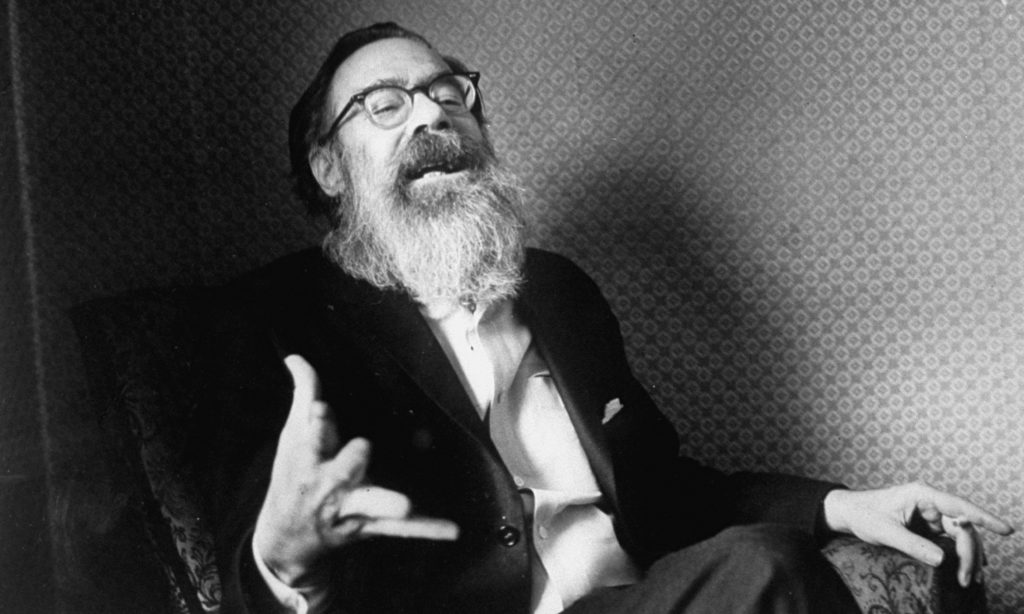

Undoubtedly, there was genius there. Where Elliot had changed modernism in The Waste Land by making frequent, bold literary references, Berryman borrowed styles. His poetry vacillated styles so (seemingly) randomly that critics sometimes thought it was just sloppiness. But Berryman would even borrow non-literary styles; poems in The Dream Songs would suddenly veer between urban patois, blues rhythms, and childlike cadences. Particularly in the case of The Dream Songs, is made sense. Henry, the narrator of The Dream Songs had suffered traumatic, scarring losses in his life, and the book is a series of artistic dreams that Henry experiences in an attempt to cure himself of the scars and the negative patterns and the misery caused by trauma. As such, Henry re-experiences things from his past and overlays them onto his present. Styles echo the sentiment or the experiencing that Henry is imagining. Berryman’s genius comes through in the ease in which Henry moves between styles and influences. It’s a well-earned ease, as Berryman was a scholar who studied a broad range of literary topics in-depth, but more importantly, because Henry was Berryman.

When Berryman was 11, his father – an alcoholic prone to bouts of depression – walked outside of the family home and stood in front of his son’s window, pulled out a shotgun and killed himself. The suicide loomed enormous over Berryman’s entire life. He often wrote of it feeling like a fate he was running from, as if his own suicide was pre-determined, and he only had hope of staving it off temporarily. Berryman eventually became a scholar and a teacher, but alcohol and depression would be lifelong battles for him. Almost as soon as he gained respect and recognition as a poet, he began to question why as frequently as he wondered why he wasn’t more popular. Another thing that didn’t rest well with Berryman was poetry’s long history of suicides or self-capitulations (a slow, subconscious suicide). Poets and writers always seemed in a battle with some innate desire to end their own lives, and that fear was always present in Berryman. That conflict between life and death was a central theme for Berryman: both the struggle to stay alive as well as the struggle between literary life (peer recognition, publishing, fame) and death (being forgotten or ignored).

I was in my mid-40s and in a low emotional place when I remembered the story of Berryman’s wave. And so I bought The Dream Songs again. This time, it all made sense. The Dream Songs – and much of Berryman’s work, in fact – lacks the themes that would appeal to an angry young man. Berryman doesn’t embrace iconoclasm as a way to shake up the system. In fact, he seems quite the opposite; Berryman uses iconoclastic methods the way a man trapped under the ice desperately searches for a hole. He pounds at the ice with one style, and when no escape presents itself, he pounds at a different place, trying on styles and languages to make a point with a desperate search for answers. He’s not an insider, contained and feeling trapped and kicking against the prison walls. Berryman seemed trapped outside, and would have enjoyed the simplicity and solitude of a tranquil life without trauma or its after-effects. His work was a testament to the person at an emotional or spiritual crossroads. To the person in middle age. To the person who needs to decide if their career is thriving or ending. To the person whose legacy will either last forever or wither and die. Being middle-aged in America is generally a time of reflection, and it was no different for Berryman. His career highs may have been higher than the average person experiences, and his career lows may have felt even more traumatic when juxtaposed against the highs. And the regular “life vs. death” internal debate he’d been carrying on since adolescence must have eventually taken its toll.

Because boiled down to its essence, all life is a series of binary choices. Binary choices which we take great pains to avoid making. We say we want to live, but then we don’t take care of our health. We say we want happiness and tranquility, but then we work too hard or save too little or don’t tend to our relationships. In my late 20s, I remember thinking I’d do “anything” to be a great writer or singer. “Anything” except, y’know, actually taking the time to write or to sing. To Berryman, life was simple; everything was either preservation or destruction. It was the decision – which path to take – that was complex. And for Berryman (and Henry), he was surrounded by despair and death and success and failure as he wandered through his life, trying to decide. Because “decision” (the very word) is rooted in finality. The Latin root of the word “decide” (“caedere”) means “to cut off”. No other options exist once a true decision is made. Berryman/Henry and most of us spend our lives in this perpetual limbo between preservation and destruction, never fully committing to either. This is not to say that “deciding to live a long and happy life” will stave off death forever. Or “deciding to work on a literary legacy” might not still yield nothing. Physical existence has its limits, and we are not in control of every element in creating a legacy. But to decide where we will put our energies resolves us to a direction. It clarifies, it removes us from a state of subservience to the tides of life, and it brings the peace that a focused, mindful sense of purpose can bring.

And that was why Berryman’s goodbye wave haunted me. It was the sign of finality, proof that a decision had been made, and I was not familiar with that kind of conviction. Had Berryman stood awhile on the railing of the bridge, contemplating whether or not to jump, it would have made more sense to me. Had he screamed or cried and begged for forgiveness the second before he stepped off the side, it would have felt more like I picture suicide. But he hadn’t. After a lifetime of fearing suicide and failure, Berryman finally made a decision about which direction he would go. And while there is incongruence in the tranquility derived from the decision to commit suicide, it’s a well-documented fact. Numerous suicides are missed because in the days leading up to it, the suicidal person seems much more at peace. Because they’ve made a decision, and despite our dislike for that decision, it has brought them peace.

It’s a mistake to presume that Berryman’s story is just about how the trauma of suicide impacts a career, the way we do with Sylvia Plath. Interviews with Berryman show that he believed that was his story. Often, he would list the writers he admired who committed suicide, and discuss the impacts that suicide had on the legacies of his contemporaries. But to me, Berryman’s story lies in that wave. While I may not support the decision he chose, I see the power of making that decision. At some point, we all have the opportunity to stop simply reacting to life and to actively pursue a direction which brings our life . Berryman’s direction may have been short-lived, but I have to believe that in those final days – and in that final moment – Berryman had found some peace. If only he had known that the peace came from the decision, not the direction.