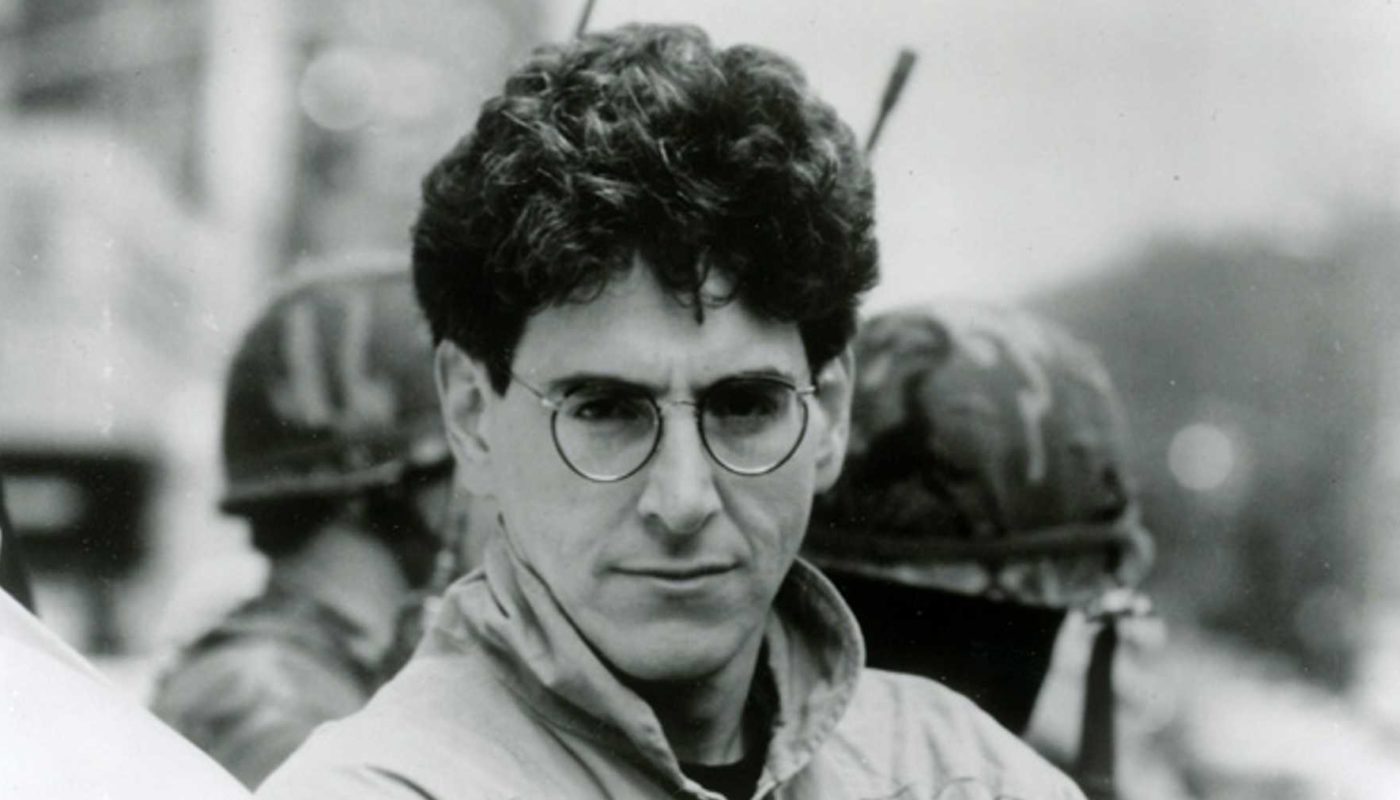

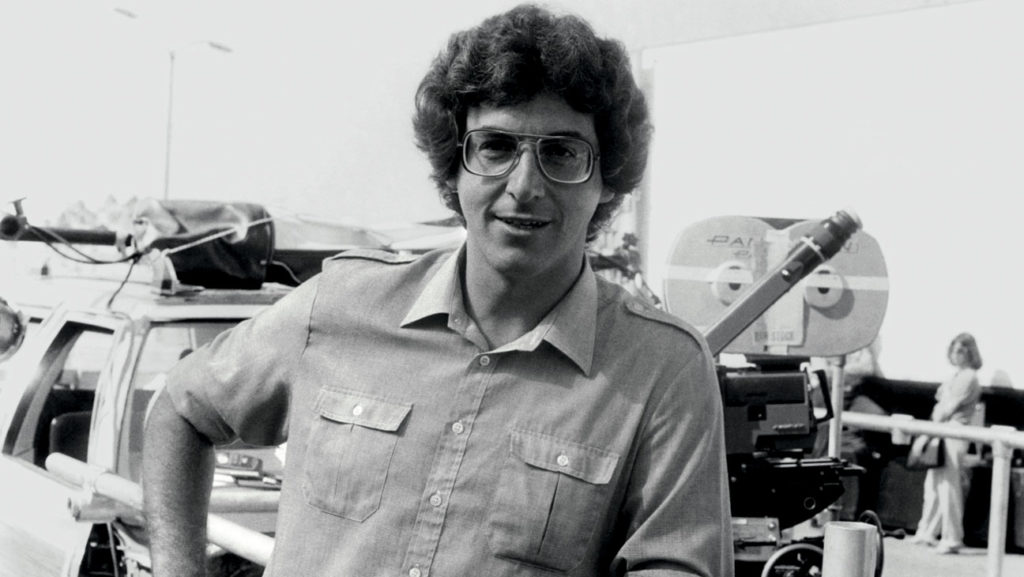

HAROLD RAMIS: November 21, 1944 – February 24, 2014

“A psychologist said to me, there are only two important questions you have to ask yourself. What do you really feel? And, what do you really want? If you can answer those two, you probably can leave your neuroses behind you.”

-Harold Ramis

Every once in awhile something I’ve recently learned about myself applies to an issue one of my kids is going through, and I share it with them. I’m not sure they even understand, as most of the time I’m only beginning to grasp the issue myself. In recent years I’ve been unfortunate enough to have things break so badly that I’ve had to take stock of my life, and fortunate enough to have been able to make a little sense of it. So when my thirteen-year old talked to me about negative self-talk that stemmed from anxiety, it was a topic I’d given considerable attention in recent years. I explained that this kind of negative self-talk was, in my opinion, a form of self-soothing – a replacement for self-care, a practice she was probably too young to understand and I was old and experienced enough to accept that I had never learned. The juxtaposition was too much for her; she flatly rejected the idea that something that provokes negative feelings could also be soothing. I explained that “soothing” or “pacifying” are not necessarily positive mental health features. I mentioned the quote about comedians (that may or may not be) from Harry Shearer, “Comedians get into comedy so that they can choose when the world is going to laugh at them.” Anxiety is like this version of comedy. The world is going to laugh at you, but maybe you can control it… slightly. For the anxious among us, “Things are going to go wrong. If I remind myself how bad I am and how deserving I am of the pain, it won’t hurt nearly as much.” It’s a form of control that is surprisingly effective as a temporary measure. But one temporary fix leads to the next, and before too long you’ve been at it for almost 48 years, and you’re listening to your child head down that path and you find yourself desperate to help her stop that cycle.

Making the world a less-scary place by pre-emptively taking blame for everything that turns to shit is a wildly self-centered act. It boils a complex world down into a single dimension, focused specifically on our own failings. It removes complexity from the world, agency from everyone else, and abdicates everyone else of responsibility for anything negative. It creates a certainty that is almost addictive, turning the mysterious and intimidating world into an easily recognizable pattern. Even as we withstand the pain being heaped upon us, it feels somehow less threatening because we anticipated its arrival. It’s unhealthy and unwise, but in many ways, so lacking the basic capacity for self-care, it also feels very reasonable option. Harold Ramis, who passed away on this day in 2014, learned how to move from that self-centered focus to a more selfless, compassionate state. In doing so, it became a theme that ran through his art, exclaiming its healing power over and over.

Harold Ramis’ comedy pedigree is as “Chicago” as you can get. He grew up in Edgewater, on the city’s north side. Raised by two working parents, Ramis and his brothers exhibited remarkable restraint and responsibility for early latchkey kids. The Ramis kids threw themselves into school and work, despite Harold’s obviously acute sense of humor. After graduating from college in St. Louis, he returned to Chicago to study at Second City, wrote for local newspapers, and write jokes for Playboy Magazine. The riots of 1968 Democratic National Convention were occurring in Old Town neighborhood where Second City was located, and Abbie Hoffman would come to the theater and improve with Ramis and the cast. When Ramis described the night Abbie was on stage while riots were going on outside, he described being curious about Abbie’s motives (he felt Abbie might have used the public stage as an alibi) and worrying about the owners of the cars whose windows were being smashed on Wells Street outside. (Dan Aykroyd would later describe Harold Ramis as “the guy at the end of the most amazing party who says, ‘That was amazing. But now let’s figure out how to get the car out of the swimming pool, okay guys?’”)) It was a turbulent political time, America – youth culture, particularly – was in upheaval, yet Ramis considered himself to be an anachronistic “combination of Groucho and Harpo Marx”.

As such, the cast of Second City developed a reputation for in-your-face progressive sociopolitical humor. Improv is naturally a collective tightrope walk, and the infusion of strong political motives often leads to disaster. Audiences often didn’t know whether or not to laugh. In improv, particularly at Second City under the direction of legendary director Del Close, the entire team would succeed together or they would fail together. But Ramis had the soul of a classic “gag man”, refined during his tenure at Playboy. He knew how to drop in a funny line here and there, so even if the sketch went down the drain his performance would be memorable. It was a self-centered tactic to gird himself from the insecurity of “failure” on stage. After relying on this technique for too long, Del Close pulled Ramis aside and gave him life-changing advice. He said, “Someday, you’re going to look in the mirror and say, ‘I’m so cute, and I’m only fifty years old.’”

For a man with an appreciation for order and responsibility, the advice was life-changing. From that point forward, Ramis worked on becoming more and more selfless. He would eventually gain a reputation as the ultimate collaborator. When he joined The National Lampoon stage shows and The National Lampoon Radio Hour, his writing was always a collaborative effort. Ramis would come up with a solid premise and some good one-liners, but he would rely on conversations with castmates to truly flesh the scenes out. It was during this period that he began his collaborative relationship with Bill Murray, which would be responsible for such classic comedies as Meatballs, Caddyshack, Stripes, Ghostbusters, and Groundhog Day (the film that would end their friendship until Ramis was on his deathbed).

For Ramis, the move from defensive self-centeredness to selflessness was a life’s mission. It seeped through in almost everything he did. His work became so relatable to so many different spiritual struggles that different movements began to assume he was a fellow traveler. Groundhog Day was named one of the greatest Buddhist films of all time, and people incorrectly assumed Ramis was a practicing Buddhist. Drug and alcohol recovery programs assumed that it was a paean to the program, but Ramis was never a twelve-stepper. Instead, he had just touched on a universal aspect adulthood: we are all vulnerable, and we can either process that in a way that is self-centered or selfless. And few people could document that learning process as enjoyably as Harold Ramis.

So as I tried to explain to my daughter that negative self-talk might make her feel a little less vulnerable in the immediate moment, it was a terrible long-term strategy. And I couldn’t pretend it was a process that I had already mastered, but it was a goal I could continue to strive towards. A learning process I could welcome and try to master. And I thought of one of Ramis’ final acting roles in Judd Apatow’s Knocked Up, where Ramis’ three minutes of screen time basically steal the entire movie. Seth Rogen, playing Ramis’ son, tells his father that he has accidentally impregnated a woman that he barely knows. Rogen goes through every configuration of self-loathing and catastrophizing he can muster, while Ramis remains positive and upbeat. He acknowledges his son’s pending challenges, but never lets Rogen forget that he’s at the beginning of a joyous blessing. Ramis’ character admits to a parent’s lifetime of faults and ignorance and hypocrisies, but never loses his refrain about what a good thing this pregnancy is. Because the accidental pregnancy is all about Rogen’s character; it’s self-centered and totally self-focused. Ramis’ character continually expands the view to include the baby, the mother, the thrilled grandparents, and the immeasurable joys of parenthood. It was a perfect role for Harold Ramis at the end of his life. I only hope that all of us eventually take the same journey and learn to turn our vulnerabilities into miracles.