Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree: Published October 7, 1964

I introduced my wife to the band Lucero yesterday. Her response to their music was similar to when I discovered them; she was blown away. We talked briefly about the talent of the band’s lead singer and main songwriter, Ben Nichols. We discussed their sound and similarities to other artists we love. It was a nice, fairly typical discussion about art, but one that until that day, I had only had with myself. I had never shared Lucero with anyone before yesterday. I’d been a fan for quite awhile, but I had never thought to share their music with anyone, despite knowing many fans of their style of music. Because I can remember the moment I had discovered Lucero, and it was literally at one of the lowest points of my life. And I had discovered it in the same room as my wife. And she had heard the same song; in fact, it was her Pandora station that had played it. And while I sat in a living room chair at a phenomenally low point, watching her do yoga and listening in despair to a band I’d never heard before sing lyrics like “It’s nights like these I feel like giving up / It’s nights like these I don’t seem to care for much”. I was blown away because the songs seemed to speak so directly to how I was feeling, and so I looked up the band and over the next few months, collected every album they ever recorded. But I never shared them with anyone else. I never told people about the new band, nor did I share with anyone why they touched me so deeply. I received their gift, and I paid the band back by purchasing albums and watching their YouTube videos, but the meaning behind the music was something I kept to myself. Ironically, I would later learn that this pattern was what helped precipitate that particular low period: my ability to give only what mattered to others, to the exclusion of what mattered to me. From my perspective, my life was one of regular, deliberate sacrifice which had eventually turned sour to those for whom I sacrificed. And without anyone to sacrifice for, I was fundamentally lost. Because giving is a complex interaction, and one that requires an understanding of who we are, who we’re giving to, and a fundamental awareness of why.

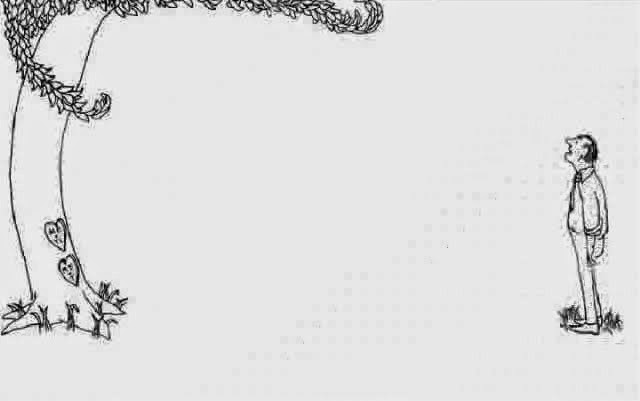

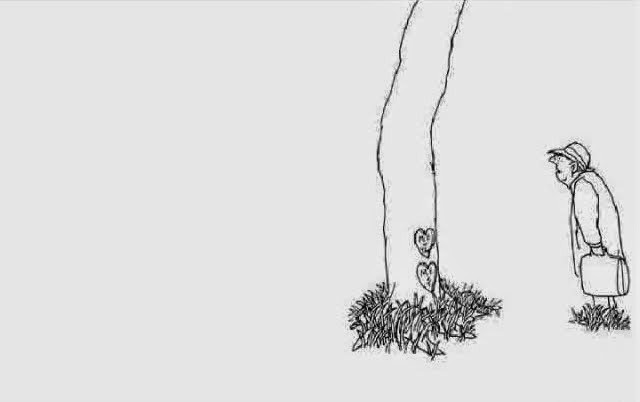

I had not yet read Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree before I learned the arguments against it. A schoolteacher aunt had decided not to teach it due to the controversy around the book’s central relationship. In the book, a tree loves a small boy who comes every day and plays underneath the tree. The tree loves the boy, and so the tree provides shade and places to climb and swing, and apples to eat. As the boy grows older, the demands of live increase and the boy spends less and less time around the tree. When the boy does appear, he has stresses in life that the tree helps to resolve. When the boy needs money, the tree gives him apples to sell. When the boy (now a man) needs a house, the tree willingly give its branches to build the the house. When the boy wants to escape middle age, the tree gives its trunk to carve into a boat. The boy returns as an old man in need of a place to rest his lonely body, and the tree offers itself – now cut down to a stump after a lifetime of providing for the boy – as a seat. When the boy sits, the tree is again happy. Plenty of elementary school teachers in the 1970s (including mine) refused to share the book, claiming that it promoted unhealthy boundaries while masquerading as a primer for joyful giving. When I finally read the book in my late teens, the relationship between the boy and the tree did feel unhealthy to me. I empathized with the tree, which seemed to give and give and give while the boy either ignored it or took the gifts it provided without showing any gratitude. I was young, and wouldn’t come to understand my own codependence for many years, but I sensed a kinship with the tree and couldn’t understand the tree’s happiness at the end of the book. Then I had children.

As Shel Silverstein fans, my wife and I made sure to provide all of his books for our children. To this day, the bookshelf above my son’s bed contains only four books of Silverstein’s poetry that we bought before his birth. We also have a copy of The Giving Tree, which I read to my kids when they were young. It was during one of those readings that I thought of The Giving Tree in a new way. Viewing the story through the lens of a parent, the tree no longer seemed like a victim of its own nature. Viewing the story as a father, suddenly the tree’s actions made sense. It made sense why the boy was always “Boy” to the tree, even when the boy was an old man. The tree was giving with the kind of unselfish care a parent feels when providing for their child. In that light, the tale made sense. Parents give to their kids without repayment and often without thanks, yet it’s not a role that breeds resentment. No decent parent feels slighted when their child doesn’t understand the effort that goes into providing for them. In fact, usually that moment is a point of pride for parents; it means the child has been provided for so well, they’ve never considered an alternate possibility and therefore they can’t even comprehend the effort involved. We teach our kids to be grateful and to say “thank you” when they receive things, but we don’t expect a quid pro quo for our giving. We love the children, and being able to feel that love is valuable enough; we don’t expect or need anything beyond that. And just as the tree gives and gives of itself and is grateful for the opportunity to provide, we grow to think that all loving relationships can work that way.

If The Giving Tree is guilty of anything, it’s guilty of simplicity – a delicious simplicity that many of us follow lovingly. The truth is, the nature of giving and receiving is as nuanced as any relationship. To deny those nuances requires selfishness or codependence. For years, I have ignored my own needs and given to the people around me, assuming I could simply meet their needs without ever having to consider what I wanted. Worse yet, I denied all of my relationships the opportunity to get closer to me. And now I am in my 40s. The friendships I have tend to be embarrassingly brief. I struggle with relationships. I am a mystery to my wife and kids. My work relationships swing wildly between “save the day heroics” and open resentment. And the trajectory of all of these relationships is similar; they all start off feeling like impossibly strong connections, until the other person begins to realize that I am nothing more than a mirror for their needs. And mirrors are for surface validation; they’re not tools for finding depth or meaning. Eventually, they resent the mirror for not providing anything but a reflection. Some walk away. Some demand depth. Some abuse the relationship. And me? I’m just left feeling confused. Because I’m just doing what mirrors are designed to do. And I’m giving of myself in the same way I would give to a child. But now, the giving that defines my relationships becomes the wedge that divides me from my relationships.

When we don’t share of ourselves, we miss out. A song plays to two people on the radio, but they never share in its meaning. Eventually, only one person even knows it exists. We can give things and give things to make someone else happy, but when our giving is not accompanied by our own feelings and emotions, we’re not building a connection, we’re simply giving ourselves away, piece by piece. At one point in my life, I thought being a worn-down stump should be the goal-state of a relationship. To be reduced to something that is only functional in relation to someone else’s need. But I have become that stump over and over, and real life doesn’t end at the happy moment when the stump feels useful for a moment. Life goes on. People have needs. And there’s no moment of loneliness as devastating as helplessly watching the only thing that gives you purpose stand up and walk away.

May we all consider The Giving Tree with the complexity that giving relationships deserve: as a testament to the importance of selflessness stewardship, as well as a warning of the destructive power of codependence.

I wish my elementary school teachers had been brave enough to share that message with me years ago.