FREDDIE PRINZE: June 22, 1954 – January 29, 1977

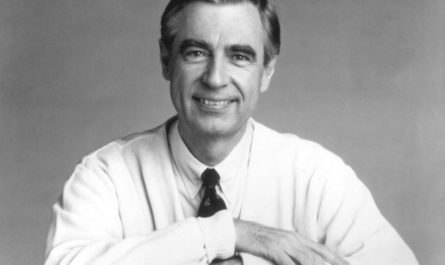

Growing up as a child of the 70s, Freddie Prinze was a mythical figure. Chico and The Man was one of the first television sitcoms I can remember watching, and I remember catching glimpses of Freddie on daytime talk shows like Merv Griffin and Mike Douglas. I recall him being charming and funny, but mostly I remember the electric smile that he had. It was a smile he flashed every time he said something funny. It was a bright and excited smile pulled forth with the muscles of the entire face, like the smile of baby. There was nothing coy or smug about it; it was genuine delight at having said something funny. Freddie Prinze may have been “cool” but he wasn’t cool enough to stop himself from laughing at his own jokes. By the time the audience laughed, Freddie was already there ahead of us. And then, one day, he was gone. Nobody shared the details of his suicide with me. In fact, nobody even mentioned that he was dead. “Chico” just left the show (replaced by a child actor and, strangely, Charo) and I wouldn’t think of Freddie Prinze again until the movie Fame mentioned him. I was an adult when I saw a “true Hollywood”-type special on him and discovered that Freddie was 22 years old when he died. The shock of that compressed timeline led me on a search to track down as much information about the man as I could find. He’d done stand-up all over, he’d hosted The Tonight Show multiple times, he had a hit sitcom, he’d even been a key performer at President Carter’s inaugural ball. He’d signed one of the most lucrative television contracts in history soon after his 22nd birthday. And then he’d shot himself in the head and died. Drugs were partially to blame. Depression, as well. Both had contributed to the fracturing of his marriage, and caused his wife to move away with their newborn son. When I would later start to research Freddie Prinze, I found that almost everything written about him was a “why?” piece. Why did he kill himself? Why would someone with so much success get depressed? Why would someone with such talent abuse drugs? Almost everything written about Freddie Prinze are notes from the aftermath, and an attempt to understand something too personal and too clouded to ever truly understand. What I never found was a search for “how”. How did Freddie Prinze achieve worldwide fame at age 19? There are biographical timelines, sure, but nothing that digs deeply into how Freddie Prinze was so appealing, and what that says – about him and us.

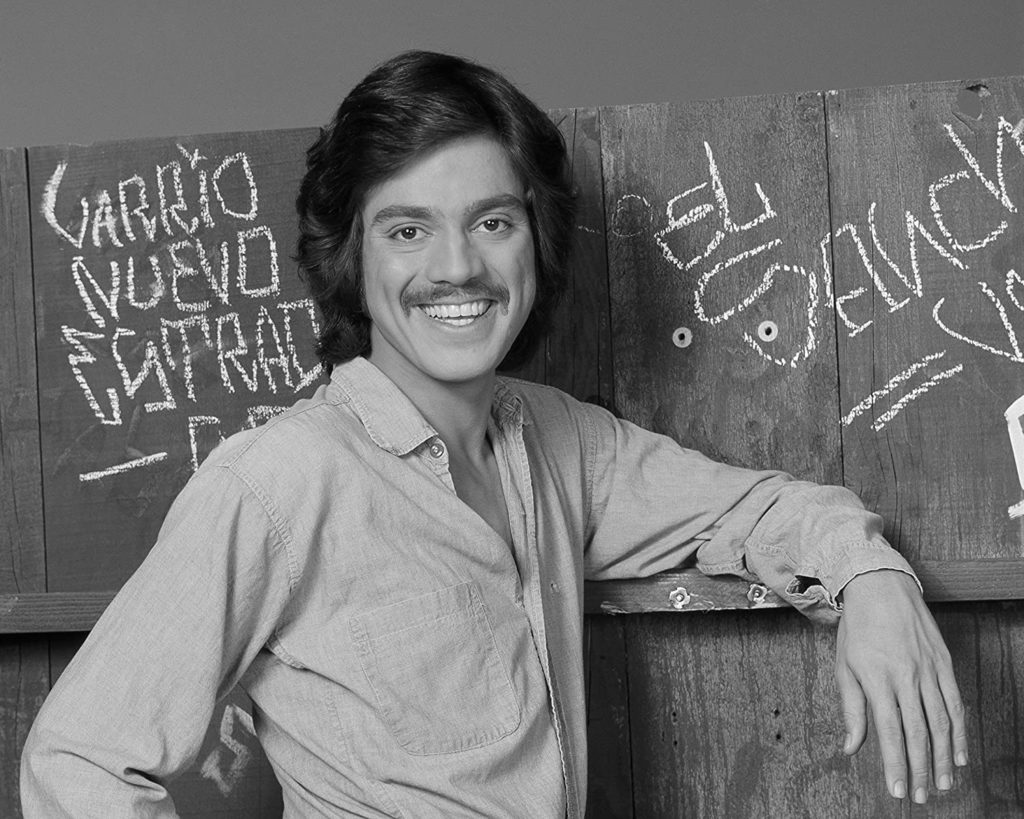

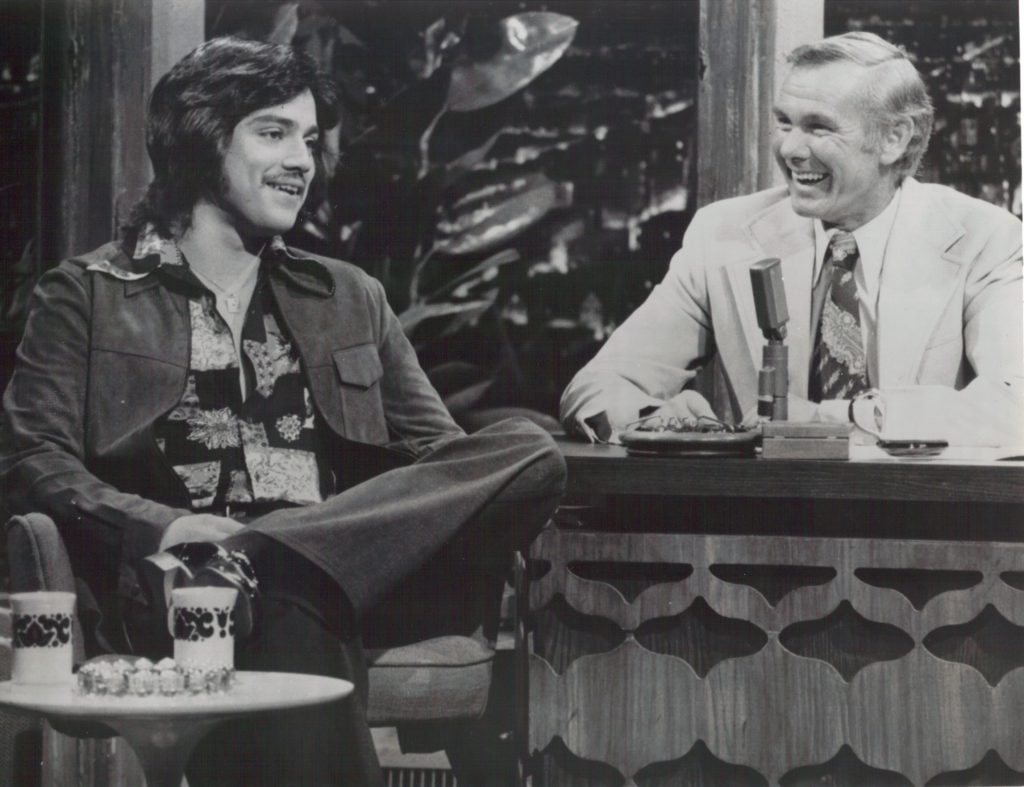

To understand the power and appeal of Freddie Prinze, a timeline is in order. Prinze grew up in Washington Heights, at the time a tough, mostly Puerto Rican neighborhood in uptown Manhattan. Chubby and unassuming, Freddie learned to avoid bullying by performing characters at school to make people laugh. He attended the School for the Performing Arts (the school from Fame) for acting and music (he was also a talented drummer), and graduated at age 18. During high school, he would go at night to comedy clubs like Catch A Rising Star to study comedians and work on a stand-up act that consisted primarily of character work. Midway through his 19th year, he made his first appearance on The Tonight Show . In the six months before his 20th birthday, Johnny Carson had him back five more times. One of those appearances sparked the interest of television producer James Komack, who created a sitcom for him. In the year he was 20, Chico and The Man became one of the top shows on television, Prinze made numerous appearances on popular network variety shows and games shows, he recorded his only comedy album (which went gold), toured extensively, and hosted The Mike Douglas Show for a week. The remaining year and a half of his life was a more-hectic version of the previous two: sitcom work, more tours, more television appearances, a made-for-TV movie, and appearances for two Presidents. (He performed for President Carter’s inauguration nine days before committing suicide.) Not to mention a marriage and the birth of a son.

It’s a dizzying timeline. In most cases, “overnight sensations” are actually the products of years of unrewarded practice and toil. By all accounts, Freddie Prinze was an exception to that rule. This became more apparent when I first listened to Prinze’s comedy album, Lookin’ Good!, which I purchased on vinyl in the early days of eBay. The truth is, the bits weren’t very original or illuminating. The premises were a bit hacky, even for the time it was recorded (the differences between New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, for instance). Like Richard Pryor, he relied on voices and characters to make the jokes work. And yet, I loved the album. More specifically, I loved him. Despite the tired premises, despite the lack of depth of the material, I loved what he did. I reminded myself that the premises were written by a twenty-year old, but lowering my expectations never felt like a necessity. I consider myself knowledgeable about comedy history and can be something of a comedy snob, yet I loved the entire album and have listened to it many times since. The bits weren’t hung together in a way that made sense, yet when Freddie would jump into a character, he would do it with such abandon, I couldn’t help but laugh. Listening to the album is like watching a child run loose in a costume shop. Every character he’d “try on” would bring him as much joy as it brought the audience, and eventually, the need for a clear narrative (or even a consistent point of view) was unnecessary. The album was Freddie Prinze’s world: silly, joyous, absurd, but never malicious or cynical. Unlike most comedy albums, I was not seduced by the material, but by the comedian. The material may not have been fascinating, but Freddie Prinze definitely was.

A few years ago, I was lucky enough to see branding expert Sally Hogshead speak at a conference. She was promoting a new book called Fascinate; The Shortcut to Persuasion. The premise of the book was that all of us are inherently fascinating individuals. We all behave and believe in ways that can be fascinating. However, far too often, we take inventory of ourselves based on how we perceive the world (Myers-Briggs Personality Indexing, etc.), not on what we have to offer the world. Traditional personality indexing is limiting, mostly because we use negative perceptions of ourselves when taking personal inventories. Those systems seek to find a way to help us “fit in”; Hogshead advocates for the opposite approach. To her, uniquely following your own passions and desires and natural tendencies not only ensures a sense of self-satisfaction, it creates the opportunity for people to be fascinated with you as a result of that passion, that desire, and that self-satisfaction. As humans, we’re inherently drawn to those qualities in others, yet the tools we use to figure out how our personality fits into the world push us towards restraining or re-focusing our passions, and remind us of all of the many situations in which we don’t fit in. Be yourself – gloriously, passionately, unfailingly yourself – and the world will find you, was Ms. Hogshead’s message. And that was Freddie Prinze. Traditionally, comedians have used their material to attract an audience. In most cases, we only know the comedian (as a person) through the lens of their material. We get a strong sense of George Carlin’s politics, or Richard Pryor’s personal history, or Lenny Bruce’s passions, but they’re glimpses. And often woefully incomplete or inaccurate glimpses, as the recent Bill Cosby scandals indicate. But Freddie Prinze’s comedy routines were secondary to the man, himself. He was so open and so joyous that the routines didn’t need to be globally insightful; nothing on that album would change the way anyone thought about anything – the way a George Carlin routine challenged us – nor were they designed to. Every bit felt like “my friend Freddie says the craziest stuff”, and while that description may sound simple, achieving that level of familiarity with an audience is near-impossible. We’re simply not that open as humans. We rarely share enough of ourselves to allow people to become fascinated by us. But Freddie seemed to give everything of himself, which made the material almost secondary.

In her biography of Freddie, his mother Maria Pruetzel told a story of how Freddie had loved to talk on the phone for hours when he was in high school. People called him so frequently, and he spoke for so long, that he looked into setting up a toll-free WATS line so his friends could call any time of the day and talk for as long as they wanted without their parents chasing them off the line. To his mother, it was a typical Freddie story, filled with outsized behavior and a downright wacky solution (the Pruetzels were far from wealthy and never could have afforded a WATS line). But underneath it lies the heart of Sally Hogshead’s “fascination” concept and the appeal of Freddie Prinze. Freddie loved people. He loved to talk to them and connect with them. He loved to do characters for them and to make them laugh. And in his mind, the kind of investment required for a WATS line was minor compared to the joy it could bring to everyone who could call him. In that case, Freddie was focused on how far his reach could extend, and how much joy he could bring to people – at no cost to them! – and that potential completely outshined the financial realities of the solution. When I watch old YouTube clips of Freddie Prinze, I’m struck by one thing: he always laughs at his own jokes. Not knowing smiles, or minor chuckles. Freddie often belly-laughs at his own jokes. By professional standards, there is no worse decorum than a comedian who laughs at his own jokes. But that was never Freddie Prinze’s problem. Because Freddie Prinze always wanted to be a comedian, but he always wanted to be Freddie Prinze more. And we found Freddie Prinze far more fascinating than we ever found his material. And so when we reflect on his short life and its tragic ending, we can focus on the “why”s. We can look for answers we will never truly find. Or we can look at the “how”. And we can see a man who embraced who he was – even if it was for too short a period of time – and followed his passions so completely that the world could not possibly turn away. We may rightfully reject the way it ended, but we can be grateful that he fascinated us while he was here.