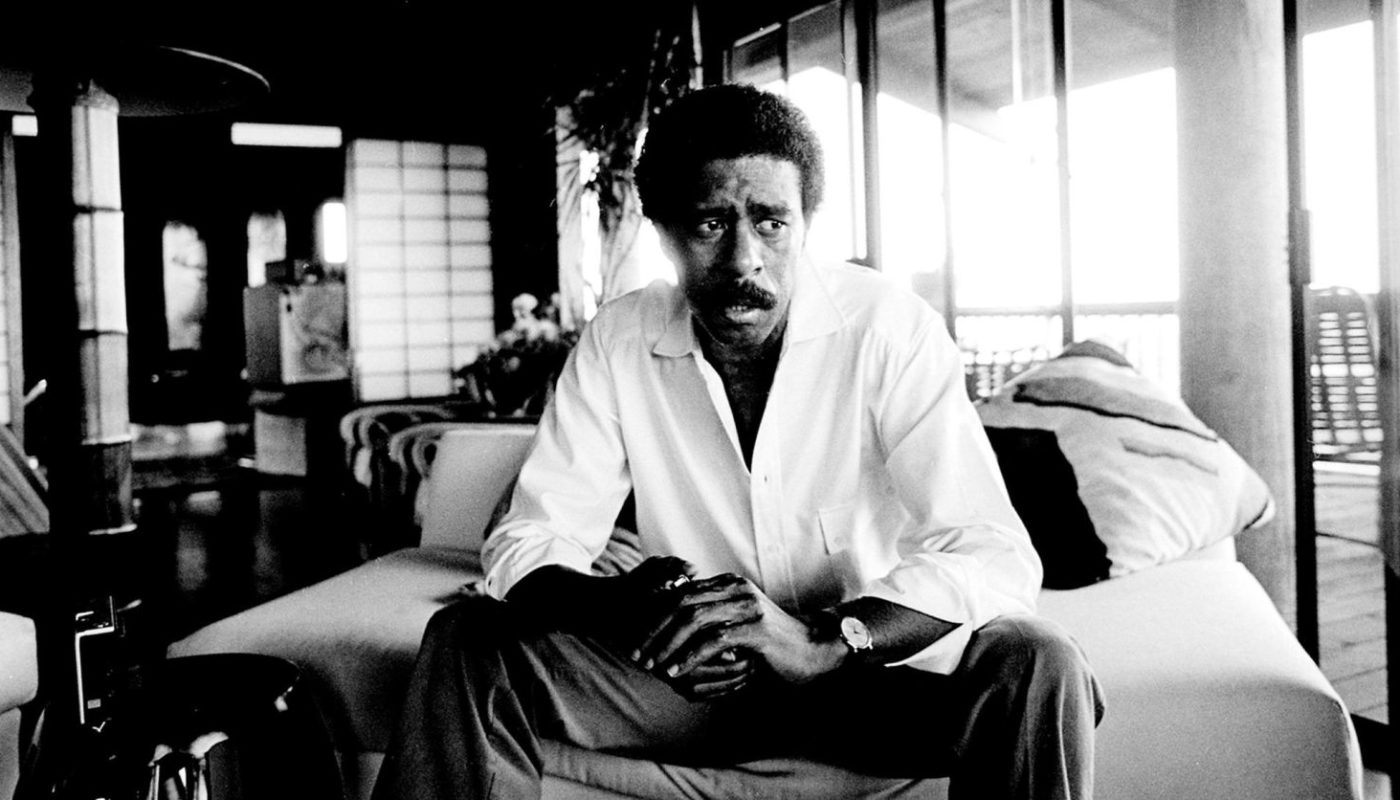

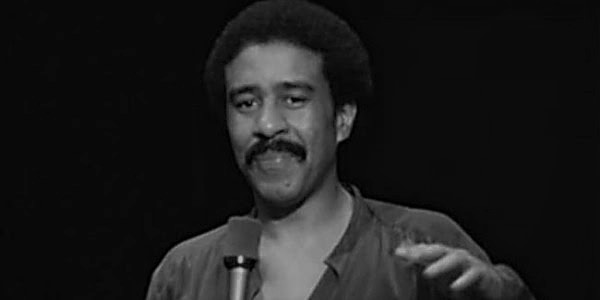

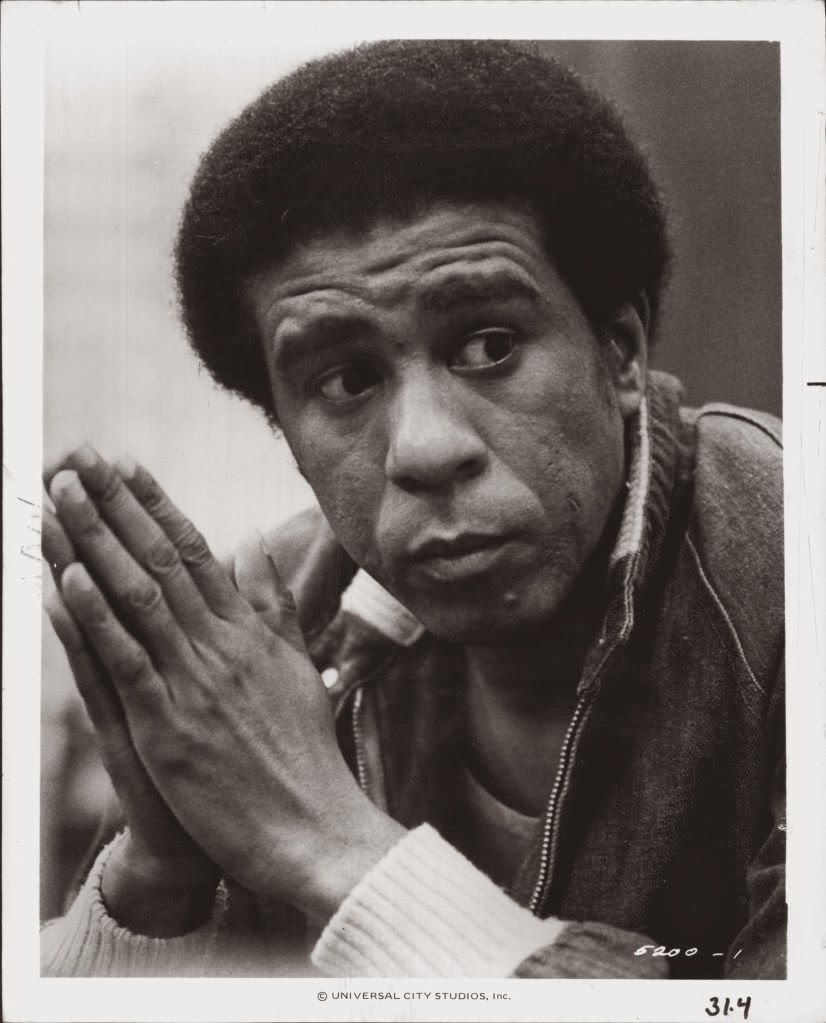

RICHARD PRYOR: December 1, 1940 – December 10, 2005

I was born with a mimic’s ear. From an early age, I could imitate the characters on Sesame Street, The Three Stooges, Deputy Dawg, funny intonations of family members, even the noises of inanimate objects. My parents hated it, but I always found comfort in pretending to be other people or characters. It was a skill that never left, and a defense against anxiety or boredom that I never stopped using. Bored at work, I would imitate co-workers. I almost lost a job over a prank where I impersonated my boss’s boss. And from the time my kids were young, they’ve loved talking to Sesame Street‘s Grover or Plankton from Spongebob or the entire casts of some of their favorite cartoons. It was a great tool in my otherwise limited parenting kit. The thing that is most surprising and the most comforting to me about mimicry is that it is not merely a function of the ear and the throat. In the moment you’re impersonating someone, it’s a function of the spirit. I suppose I could laugh like Elmo without feeling the glee beneath it, but I’m not sure I know how.

When anyone lists the greatest comics of all time, Richard Pryor is always in the top three. In my life, I’ve met people who don’t necessarily love Pryor’s work, but I’ve never heard anyone not recognize his genius.

If I were to rank qualities that make a great comedian, I can certainly think of comedians who were quicker on their feet, and I can think of more polished comedians, and I can even think of comedians who delivered more powerful social commentary. What set Pryor apart, though, was the humanity he brought to his comedy. When Pryor spoke, he never seemed to be lecturing. Even when he would openly lecture, it never felt like there was a power imbalance or a transfer of knowledge. Because Pryor would walk us through the process he had experienced, personifying the process and allowing us to understand it on the same depth as he did. All of the characters and conversations would be played out for us – by Richard Pryor.

Even as a mimic, there were more competent comedians. Eddie Murphy immediately comes to mind. But Eddie, like most mimics, used his vocal talents to make an ordinary premise absurd. But Pryor didn’t need to rely on absurdity or silliness. Pryor provided insight into an experience. He could switch so effortlessly between characters – vocally and physically – that we experienced all of the elements in his learning process as completely as he did. But the history of comedy is filled with great storytellers, yet very few embodied their characters as completely as Pryor did. What drives a person to immerse himself so thoroughly in others as a method of communicating with others?

Conventional wisdom says that Pryor’s turbulent youth was the foundation of his comedy. And there’s perhaps some truth to that. Certainly, it could be argued that he would have wanted to find avenues of escape in his childhood. But all of the stages of Pryor’s life and career – the middlebrow clean comedy, the blue act, the countercultural awakening of the late 60s, the post-Africa/post-freebase personal awakenings, even the movie career – were a process of paying attention and soaking in everything. In 1959, Pryor was a 19-year old soldier stationed in Germany. One night at the movies (Douglas Sirk’s Imitation of Life), a white soldier laughed a little too loudly and joyfully at some of the racist portrayals in the movie – portrayals common to the time. Pryor, filled with rage, followed the white solider out of the theater and beat and stabbed him (not fatally). But to think of a young Pryor so angry over what (sadly) was likely a fairly commonplace occurrence for the time shows just how emotionally raw he was. How his interactions with the world didn’t simply roll off the emotional armor most of us gird ourselves with just to exist, day to day. Pryor wore no such armor; instead, he learned how to escape.

What’s more fascinating about an incident that powerful – and Pryor would experience many of them in his life – is that it didn’t define the course of his life. It altered it, certainly, but that’s commonplace. A bad break-up, a good restaurant, a shortcut to work… all of these things can alter our lives. But Pryor did time for beating and stabbing a man. He got kicked out of the Army. But it didn’t break him. He didn’t return to the States and give up; he returned to the states and was opening at the Village Gate within a year. It seemed that no tragedy could break him: not his childhood, not the freebase explosion, not multiple heart attacks or divorces or addiction. In the face of a life of wild success and terrible tragedy in a world filled with absurd hypocrisy, Pryor remained raw and vulnerable and almost completely empathic. And everything he experienced – whether he loved it or loathed it – just added more depth to the well from which he drew.

In the end, mimicry is a circular process of understanding the world by embodying someone or something (often time, anything) else. And to many of us, we chase that process. It’s a desperate sublimation; a blessed escape from ourselves just long enough to experience the world as someone else, entirely. And by doing so, to experience the relief of seeing the world through a new set of eyes, through a new body and brain, through a new set of emotions. And then, as quickly as we began, to return to ourselves. And on our best days, we return ever-so-slightly wiser. Ever-so-slightly better.

Some of us are born with a mimic’s ear. But, for better or for worse, it’s life that grants us a mimic’s heart.