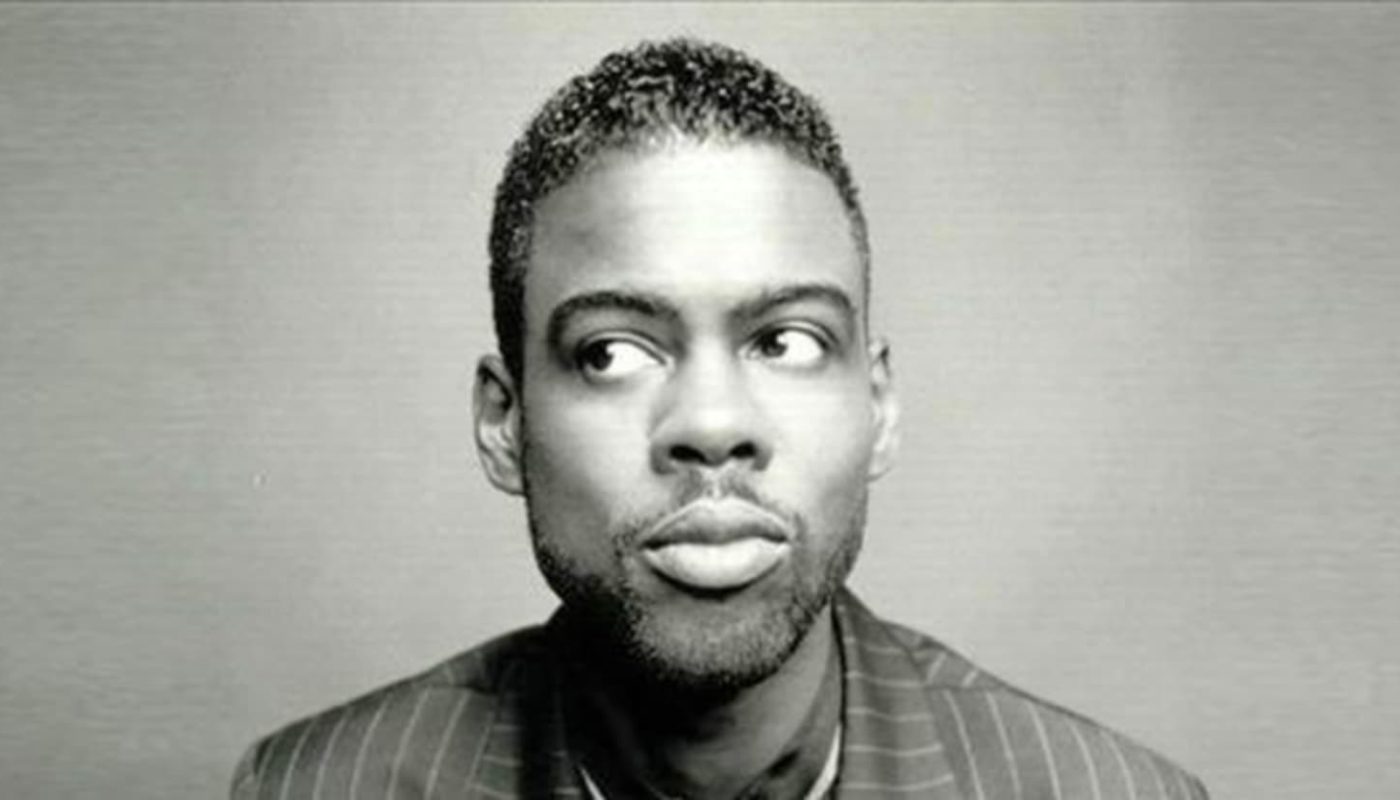

CHRIS ROCK: born February 7, 1965

If there was a predominant sentiment in the 1990s, it was apathy. The introduction of Generation X to adulthood created a perfect storm of contradictory emotions. Gen Xers were angrily argumentative, but hopeless and skeptical. Nirvana was the perfect band for its time, arriving on the scene to destroy the hyper-sexualized party-child ethos of glam metal. In its place, a hollow scream of barely-comprehensible lyrics (“a mulatto, an albino / a mosquito, my libido”?): all rage and little substance. The timbre of the 1990s wasn’t revolutionary. It wasn’t a call to arms. Moments of “I have a dream” inspiration were few and far between. More than anything, the 1990s felt like a protracted tantrum – full of sound and fury, signifying nothing. The comedy scene in America was no different. The early 90s was the height of a comedy boom in America, ushered in by the creation of the Comedy Central network. In its earliest days, Comedy Central showed nothing but stand-up comedians and created a groundswell of excitement for stand-up comedy. Soon, every bar and stage in America was hosting an open mic comedy night. Night clubs turned into comedy clubs. By the 1980s, stand-up comedy had evolved from the one-liner comedy of the 1950s (“Take my wife, please.”) to an aggressive, hyper-political art form (Richard Pryor, Lenny Bruce, George Carlin). But by the time the comedy boom arrived for the Gen Xers, it had returned to safe, observational comedy: airline food, weddings, the difference between men and women. And so it was a confusing time to be a young, gifted, African-American comedian like Chris Rock.

Chris Rock rose to fame in the 1980s New York comedy scene. A regular at Catch A Rising Star, Rock was befriended and promoted by comedy greats like Eddie Murphy and Jerry Seinfeld. In 1990, he joined Chris Farley, Adam Sandler, David Spade, and Rob Schneider as the newest cast members on Saturday Night Live. The five were quickly dubbed “the Bad Boys of SNL”. And while the other quickly rose to stardom on the show, Rock was noticeably under-utilized. In the meantime, Rock recorded his first comedy album, an underwhelming performance called Born Suspect. He then starred in his first comedy special, Big-Ass Jokes, which was also extremely uneven. By 194, Rock was an exemplary comedian of his generation. He was clearly funny and insightful, but Rock was more of a cocky genius than a comedian. He could take a great premise and miss 99% of the potential jokes, or take a mediocre premise and deliver a knockout punchline. He was clearly bright and charismatic, but unfocused. More importantly, he carried himself with the confidence of a comedy legend, but his jokes were lightweight affairs and he committed the most unpardonable sin among comedy greats – he laughed (hard) at his own jokes. He was the comedy equivalent of a Kurt Cobain lyric scream – powerful and commanding, but ultimately meaningless, save for the power of the scream itself. And (like Cobain) it made him a big success. That should have been the end of the story.

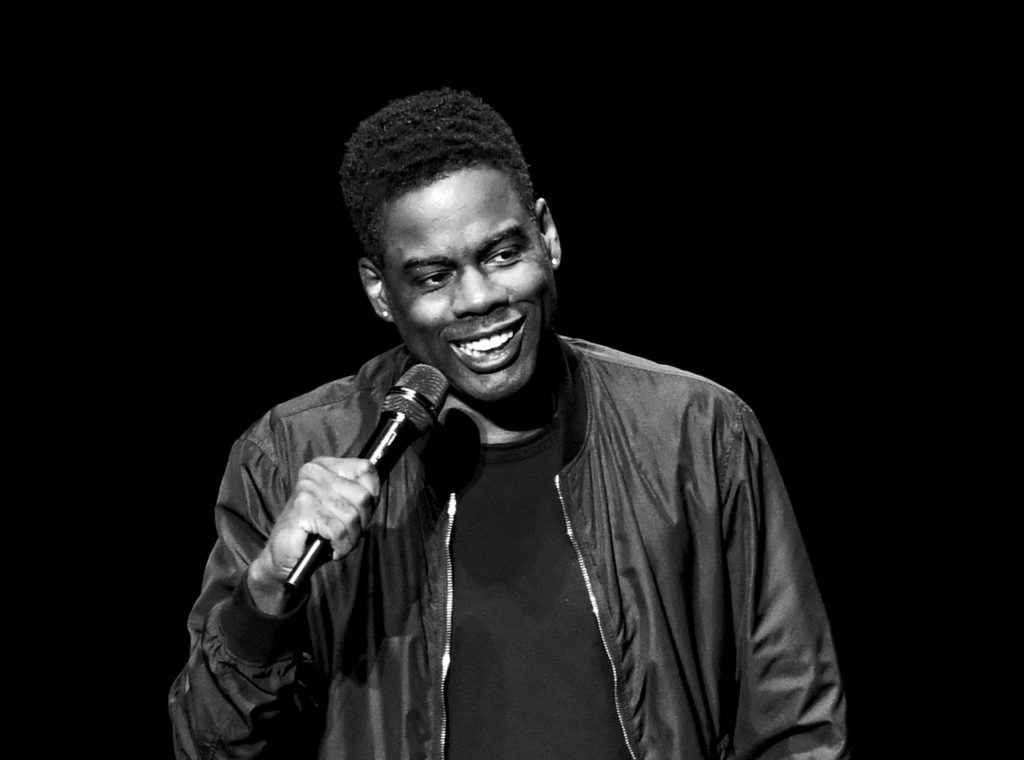

But at some point in 1994, Rock decided that he didn’t want to be a successful comedian making irrelevant commentary. He wanted to be a comedy legend. He was 29 years old. He’d spent ten years mining his life for new jokes and new premises and his comedy never got more substantial. His career was on a downslide, but he was good friends with Eddie Murphy and saw what success looked like. As he neared 30, Rock publicly questioned whether he was a “has-been” or a “never was”. And he knew that if he was never going to be successful like Eddie, he could at least be honest – and at least be good. So he returned to the woodshed. He studied every great comedian. He listened to the albums of legendary comedians. He watched great comedy performances. He studied how to craft jokes the way legendary comedians did. Instead of relying on youthful exuberance and charisma and an innate sense of humor, he looked to learn from those who had truly changed the comedy landscape. And after spending a year immersed in the study of great stand-up comedy, Chris Rock emerged with his comedy special Bring The Pain. And from the very first bit – a commentary about having disgraced DC mayor Marion Berry on-stage at the Million Man March – it was apparent that a new Chris Rock had been born. By the end of the hour-long special, Bring The Pain was clearly one of the greatest hours of stand-up comedy ever.

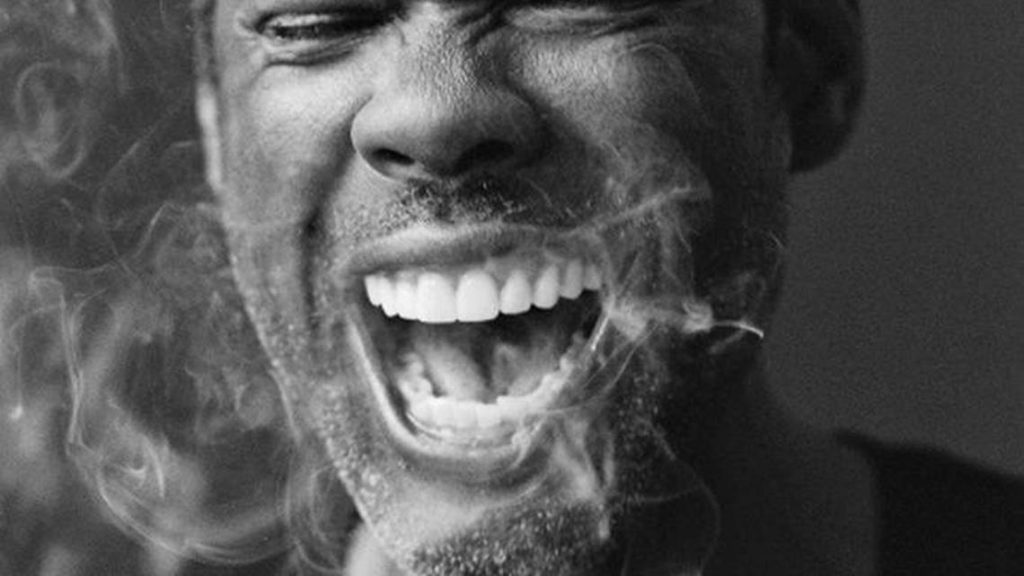

Because, in learning to craft a joke, Chris Rock learned clearly learned how to articulate his own thoughts with a depth previously unheard. It would be foolish to assume the depth of Rock’s beliefs didn’t exist before, but Bring The Pain brought it into focus. By learning how the greatest comedians craft their bits, he also learned how to get to the heart of a joke, and in Bring The Pain we learned that the heart of Chris Rock’s jokes was a fearless, political center. Previous Rock bits addressed racism and sexism with a scattershot randomness. There was no cohesive political agenda, and the target of his outrage could have been anyone. In Bring The Pain, Rock made everyone a target. Bring The Pain’s first 30 minutes made fun of white America’s misrepresentation of black America, and it’s second half focused on black America’s culpability in that misrepresentation. Rock called out misogyny and violent males, but liberally interspersed jokes about women taking advantage of general rules of decorum to publicly emasculate men. Rock’s education from the comedy masters allowed his outrage to be universally broad, yet still held a well-articulated position. We were all crazy, according to Rock, and all deserved to examine our motives and actions.

Bring The Pain was a revelation, and catapulted Rock (deservedly) into the status of a comedy legend. He opened the doors for important comedians like Dave Chappelle and Louis C.K., whose comedy was a blend of personal and political. More importantly, he re-introduced the fading sense of purpose in stand-up comedy, and comedy returned to the social satire of its heyday in the 1960s and ‘70s. Rock’s path was the perfect antidote for the combative apathy of the 1990s GenX crowd. The irony of the situation was that the GenX attitude in the 1990s was a rejection of the generations who had come before, but Rock only found his voice by studying how previous generations had articulated their outrage. Yet Rock never had to relinquish his skepticism. Rock remained skeptical of the world yet still avoided a worldview painted in fundamental, “all is lost and all previous generations have forsaken us” broad strokes typical of his generation (and typical of his early career).

Because that screaming voice of a combative, impotent generation is easy to fall prey to. It’s a voice that is aware of a profound dissatisfaction, but isn’t exactly sure why it is dissatisfied. Nor does it have an idea what to do about it. And part of growing up is taking the time to contemplate those “why”s and “what to do”s in a world that doesn’t necessarily require those answers. Left to our own devices, we dismiss the generations who have already wrestled with these questions, and we’re left to answer questions in an emotional vacuum. Chris Rock was smarter than that. And if this project has taught me anything, it’s that we can learn from any number of resources. That the momentsof inspiration we glean from others create a roadmap, not to be like those inspirations, but to create a collective picture of our thoughts and beliefs. By looking to those who inspire us and have found answers on their own, we create a new picture that is uniquely ourselves. And when Chris Rock broke with the standard isolated voice of his generation, he found his voice… in the voices of the legends who walked before him.