The Wild Bunch: premiered June 18, 1969

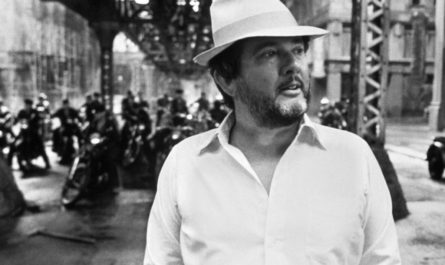

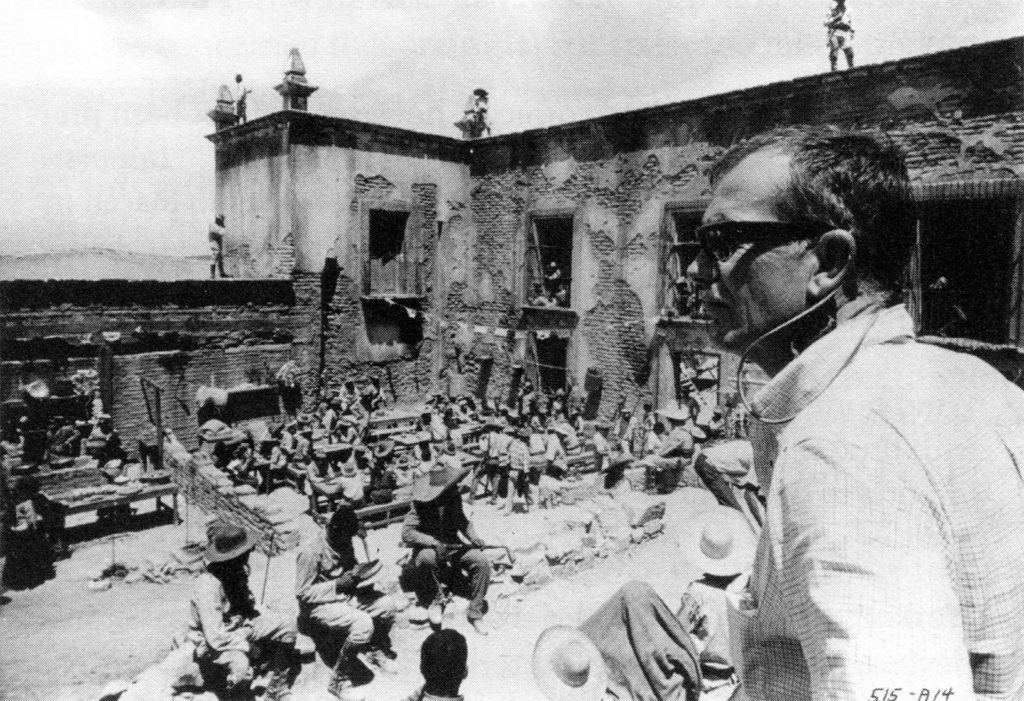

When Warner Brothers screened Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch for the MPAA and assorted film critics in 1969, the reaction was decidedly mixed. It was a Western, but a Western without heroes. The protagonists spend the film working for the villains. The Wild Bunch themselves was a broken-down pack of worn losers, and the film’s moral center was a tool of a fascistic railroad. The film started with a robbery and cold-blooded murder by the protagonists, and ended with an entire village being slaughtered, including the angry murder of a woman. 1969 was the beginning of an era of anti-heroes in cinema, but even then, seeing William Holden play a cowboy who angrily calls a woman “Bitch!” before shooting her dead was shocking. And none of this takes into account the violence of the picture. The Wild Bunch is easily one of cinema’s most artistically, realistically violent pictures. Peckinpah started by using advanced camera techniques, hundreds of extras, and hundreds of thousands of bullets. But the true violence was in the glee of it all. When the Mexican Army drags one of The Wild Bunch behind a car, the villagers cheer and celebrate. Children hop on for a ride. It was all too much for some critics, who stormed out. When the film ended, critic Rex Reed attacked Peckinpah’s character and amorality during the post-screening press conference. But Roger Ebert, when given a chance to speak, offered up a defense. He knew that the film was brilliant, and would usher in a new era of cinema. But what was the film’s message? That the West (expansion, imperialism, manifest destiny, pioneering) was dead? That violence is pointless? That the world is a morally ambivalent place? That you can’t trust the good guys?

The genius of The Wild Bunch is that all of those are true. It’s a film so rich and contextual that it truly can mean multiple things to anyone. And it has always been in my list of Top Five All-Time Favorite films for different reasons, at different times. Lately, I’ve been viewing it through an entirely different perspective.

If you’ve read or followed this blog at all, you know that my purpose for writing it is to show my gratitude for the people, places, and things that have helped shape my worldview. I started it at a time in my life when I was very lost, and I used the process to try to understand how these things which have moved me so much were either reflections of my beliefs or beacons that I had altered my life to follow. I wrote sporadically. Generally, I wrote when I believed that I understood my world. And so long periods of silence would occur as things grew busy or confusing, and when the dust would settle I would start to write again. Sometimes it would last a day, sometimes a week, sometimes longer. Life would be good and I would write. Life would turned bad, and I would retreat to being a spectator of the things I love, and try to figure out some perspective. Today is the first time I’ve written when things were bad, and it seems that The Wild Bunch is the perfect topic.

Because this is me writing from “the bottom”. Details aside, in almost no time the shaky house of cards that was my life finally collapsed, and I’ve come to recognize myself as a failure in almost every aspect of my life: mentally, emotionally, physically, spiritually, economically. There are moments in life when you have to acknowledge that “doing your best” is simply not enough. And here, at the bottom, I’ve come to acknowledge this fundamental insufficiency, even if I have yet to accept it. Because it’s one thing to recognize the actions in which you have failed; it’s another entirely to finally admit that your character is fundamentally inadequate. Moving from “a man who fails” to “a failure as a man” is a big hurdle. It’s a hurdle that exists primarily because accepting that reality leaves one question: “What can I do about it?”

The bitch about being a failure is that there is no fix for it. There is no redemption. Which is why I’ve always bristled at the criticism that calls The Wild Bunch a film about redemption. There is no redemption in The Wild Bunch. Having achieved meager, end-of-the-road success, The Wild Bunch lose one of their own, the Mexican member Angel, who gave an extra case of guns to his native compatriots who were being killed by the Mexican Army – the very army that the Wild Bunch just stole sixteen cases of guns for. For their efforts, they earned a few small bags of gold, enough to eke out an existence for their remaining few years, provided they show a prudence they’ve never before exhibited. For Angel’s act of friendship and assistance, he is tortured and murdered by the Mexican army. The Wild Bunch, on the run from railroad-funded bounty hunters, hide in the Mexican village being occupied by the Mexican army. They watch their friend being tortured by the village. They start to blow their money on whores and booze. And in the final act of the film, they take stock of themselves.

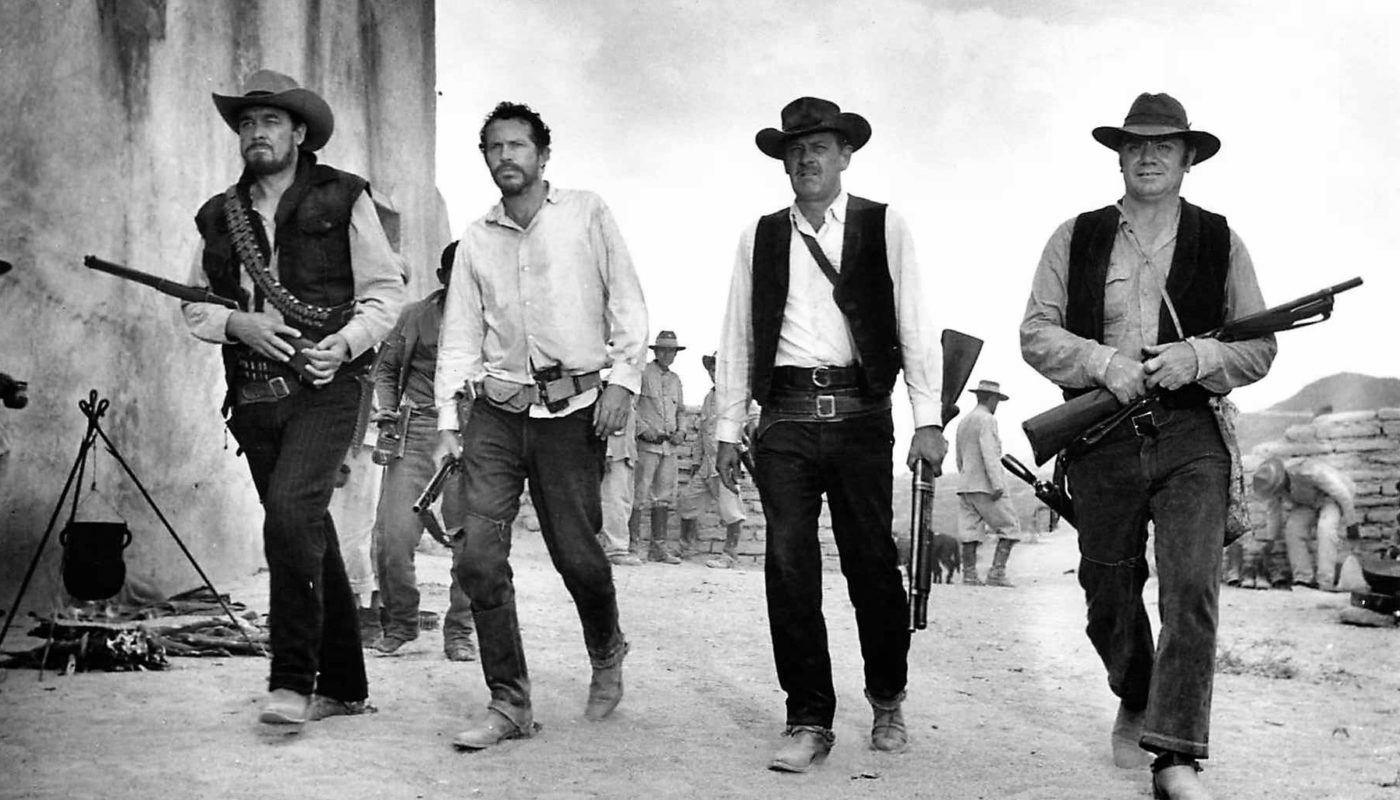

Pike Bishop (William Holden) finds himself drunk with a prostitute who speaks no English. She attempts to pretty herself for her next customer, as her infant cries in the corner. Lyle (Warren Oates) argues pointlessly with another Spanish-speaking prostitute over money, which he knows will dwindle fast. Tector (Ben Johnson) finds the bird he has captured for a pet is dying on the string he has attached it to like a leash. And Dutch (Ernest Borgnine) sits in the shade, whittling. It’s all pointless. The Wild Bunch has just pulled off a dynamic train heist to set themselves up for the future, and it’s all been a failure. They’re hunted for a criminal past, they’ve failed to protect one of their own, the money they counted on is dwindling and represents a momentary flash of happiness. A gold piece may buy you companionship long enough to forget your problems, but when it’s over, you’re left with the sad loneliness of the situation. So what do you do in the moment that everything you’ve done is a failure? What do you do when the plans you’ve made have been exposed as piss-poor attempts at respectability? What do you do when a lifetime of failed attempts finally settles into a failure of a life? For The Wild Bunch, they stood up and they walked.

I’ve always felt that the most dramatic moment in The Wild Bunch wasn’t the extended, hyper-violent gunfight at the film’s climax. I always felt that the film’s most dramatic moment was the walk into the gunfight. Because as they walked to the village square, into the heart of the Mexican army’s stronghold, they had no idea what would happen. They would ask for Angel back, they knew. But they also knew that this – like everything else in their lives – was destined to fail. They may have known that things were destined to fail, but the important part was to just keep pushing. It’s arguable that they were pushing for their own death – the only comment about the walk into the village square was Lyle’s defiant, “Why not?” – but the fact was, they pushed. When it all fell apart around them, they just kept pushing forward. Because sometimes, that’s the only thing we can do. There may not be a light at the end of the tunnel, but it’s really the only option left. There is no choice but to go forward and handle whatever comes with as much dignity as humanly possible. The Wild Bunch weren’t looking for redemption. They were looking to fail on the least-offensive terms possible.

The sad and scary part of failure is that there is no clear path. There is no path to eventual success. As a result, there is no real path. You just move through life with the hope that your mistakes don’t harm too many people, that your presence doesn’t leave too many dissatisfied, that your love doesn’t leave too any people scarred, and that your existence doesn’t leave the world too damaged for having been here. And so you walk. Not to redemption. You walk to the next failure, you walk to certain death, you walk to whatever. But you just keep walking. Because… why not?