CHRIS FARLEY: February 15, 1964 – December 18, 1997

For a fat guy, Chris Farley could sneak up on you. When I think back to the night I learned of his death, it feels like I had known Chris Farley my entire life. I had finished up my last final of my long-overdue college career, and as I drove north to meet a friend at a bar, the dj’s on the radio were talking about Farley’s death, earlier that day. I was on Lake Shore Drive, within site of the Hancock Center (where he lived and died) when I heard the news, and it broke my heart. I loved Farley, like everyone did. I wanted to be more like him. I wanted to be fearless and dedicated to the laugh the way he was. And I wanted the best for him, since he’d become such a huge influence. It was years later that I realized that Farley had really only been on my radar for about six years, at that point.

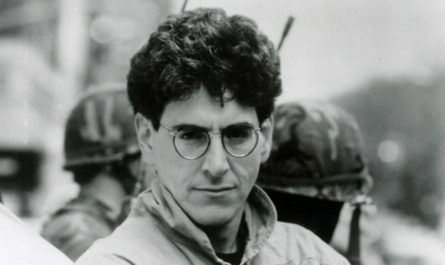

In the years I hung around the edges of the Chicago performance community, Farley was beginning to make a name for himself at SNL. It seems like he went from a typical cast member to a breakout star with the first appearance of “The Chris Farley Show” in October of ’91. As his star continued to rise, so did the volume of stories about him. Legendary stories of his antics at Burton’s and The Old Town Ale House and other now-forgotten Old Town bars near Second City. And despite the fact that Farley returned to Chicago often and was rumored to have maintained an apartment there, I never ran into the guy. Or even ran into anyone who had run into the guy, they way people would run into John Cusack and Lily Taylor and John Mahoney and Brian Dennehy. Farley was a legend in size and scope, and the tales of his antics were always of being the loudest, wildest guy in notoriously loud and wild places, and yet he seemed to be invisible to the city.

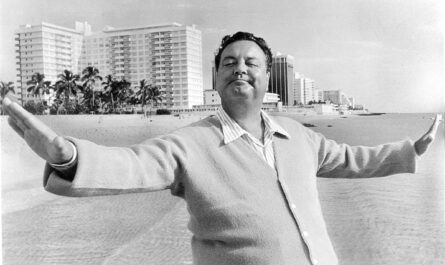

That has always seemed like an apt description of Chris Farley to me. It’s a description that is equal measure of amazement, delight, and fantasy. And what was always lacking in those descriptions? Stories of Farley’s tender moments. Stories of Farley’s thoughts or his beliefs. Stories of meeting John Cusack are usually tales of talking music or film or politics. I never heard anything like that with Farley. I remember reading an interview with Chris about a year before his death in which he described the development ups and downs of the Fatty Arbuckle biopic he had been trying to make for years. Farley had attained some buzz in the industry when the vocal tracks he had recorded the title character in “Shrek” were abandoned (later to be re-recorded by Mike Myers). The tracks were supposed to be filled with pathos – sadness with comedy at the center – but removing Farley’s physicality from the mix just highlighted his sadness. The tracks were too raw to every work, but that rawness made the industry believe that a sober (or “sober enough”) Chris could pull off the dramatic parts required to tell Fatty Arbuckle’s story. When the interviewer asked Chris about the possibility of dramatic roles, Chris responded, “I signed on to be the clown.”

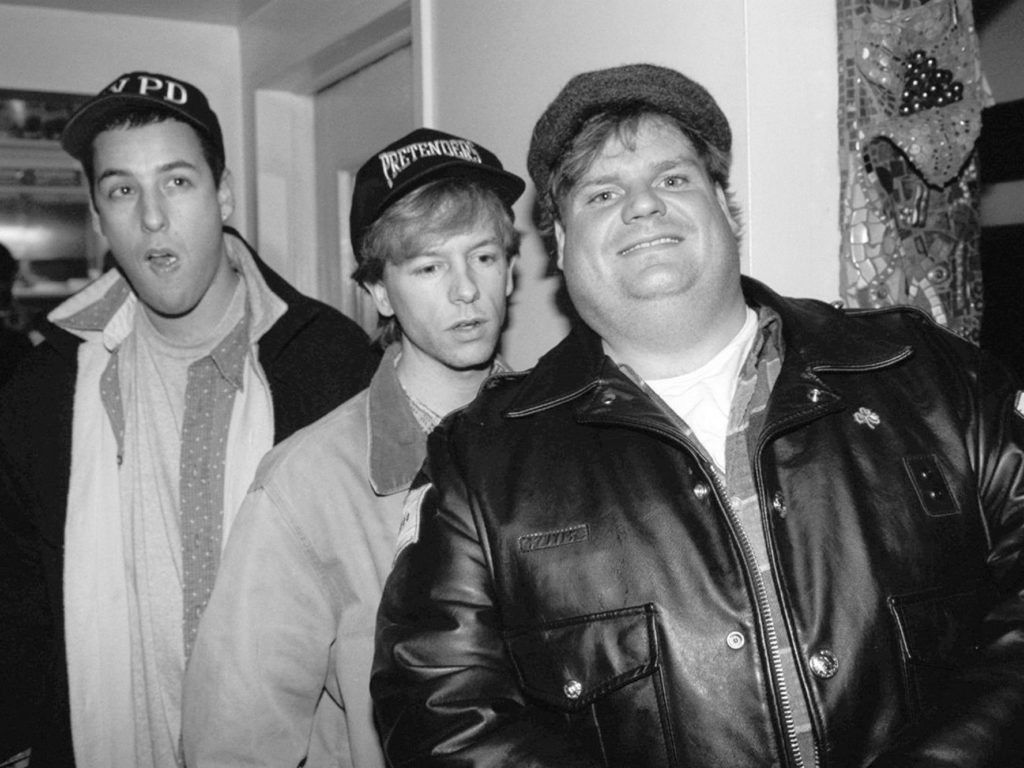

Being the clown was Chris Farley’s gift and his curse. In nearly every article, interview, or book written about Chris after his death, people detailed the lengths Chris would go to for a laugh. How Chris, who was naturally shy and self-doubting and worried about how others perceived him, would simply blow past concern and self-preservation and even past reason and decorum. His approach to humor was influenced heavily by Del Close and John Belushi, both of whom crafted the idea of comedy as a literal attack on an audience. Chris’s standard attack was to toss off anything resembling inhibition in an effort to make people laugh. While this may be an admirable trait, it is also a risky line to walk because the comedian in that situation all too often becomes the joke. Which Chris did often. When Chris Rock was interviewed after Farley’s death, he talked about Farley’s “Chippendale audition” sketch, which regularly considered one of the funniest moments in television history. Rock took a different opinion, based on what the sketch said about his friend:

“Chippendale’s was a weird sketch. I always hated it. The joke of it is, basically, ‘We can’t hire you because you’re fat.’ There’s no comic twist to it. It’s just fucking mean. Chris wanted so much to be liked. As funny as that sketch was, it’s one of the things that killed him.”

Somewhere along the way, the ability to make people love him through the funny things he did and said robbed Chris of any individuality. He eventually became the source for laughter, but not a source for connection. One of the more haunting videos that surfaced of Chris Farley after his death was from his time in rehab. Weeks into rehab, he took part in a “variety show” of sorts. It was intended to give people an opportunity to discuss their habits and addictions in a creative way. Chris joined in, and was hilarious. The entire group laughed heartily, but one thing was very apparent: Chris Farley was making people laugh, not getting in touch with Chris Farley. It was a sad moment to see somebody so skilled at what they believe is important, but to have lost himself so completely in the process. It’s a process I personally understand more now, but at the time it felt foreboding and sad.

It’s often been said that our greatest strengths are also our greatest weaknesses. In Chris Farley’s case, that is certainly true. But it’s likely true for most of us. As we become more proficient and stronger in some skill or personal attribute, we rely on it more and more. We become “the funny person”. Or “the caretaker”. Or “the shoulder to cry on”. And we hone this role as people rely on us more and more. And the more time we spend in this role, and the more we find validation in it, the more the role begins to dictate our decisions and our behaviors. And the less we have to actively make our own decisions. And slowly but surely, the exemplar we are in the one area robs of us the complete human we should be. And so it was with Chris Farley. When he died of an overdose, alone in his apartment, we mourned the loss of laughter and we dreamed on what could have been. But only those closest to Chris mourned the fact that the Chris who had died had become a hollow shell of the Chris they loved, and the Chris they always wanted to see. The rest of us never even considered that Chris. And perhaps Chris Farley never felt useful unless he was dancing for us. All evidence certainly seems to point to it.

But I have to believe that if Chris could have learned to believe in the possibility of love without that dance, we’d still be laughing with him today.