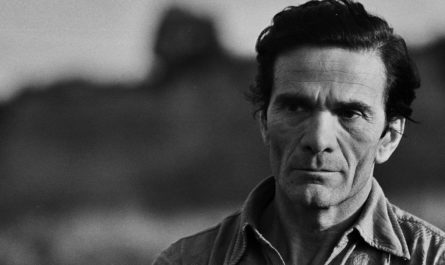

THELMA SCHOONMAKER: Born January 3, 1940

Editing film is a thankless profession. At its most functional level, editing is merely the process of slicing and splicing shot after shot into a single roll of film. In the hands of a competent director, editing can be a workmanlike endeavor with no creative input required. But when handled by a true artist, the editing of a film creates a subtle layer of emotional subtext, deepening the audience’s connection to the work. The problem with editing, then, lies with the audience. When editing is done in a workmanlike manner, very few people blame the editor. When editing is done by a true artist, very few people credit the editor. But brilliant editors exist. One of the most brilliant is Thelma Schoonmaker.

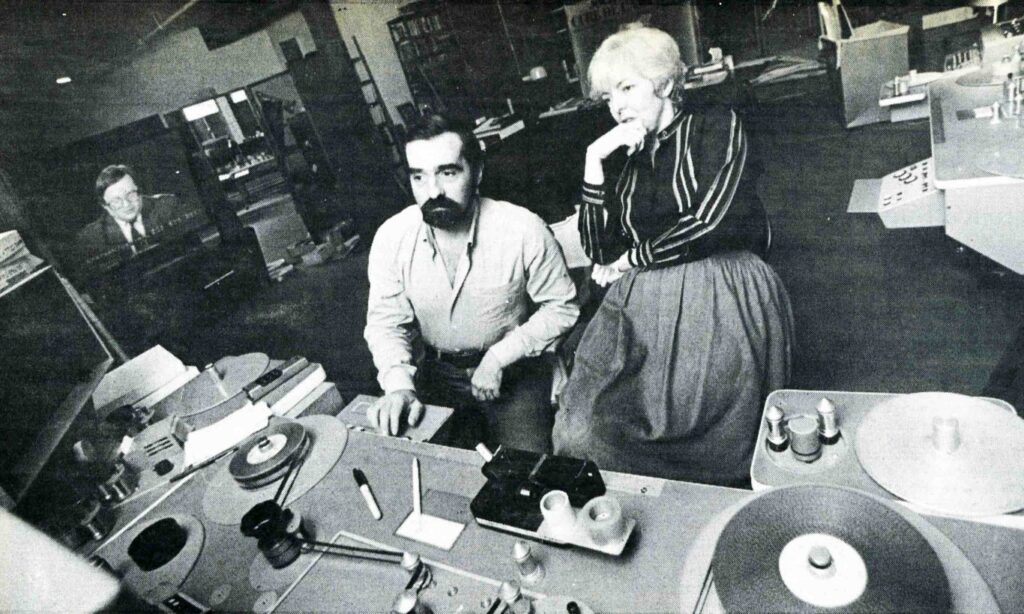

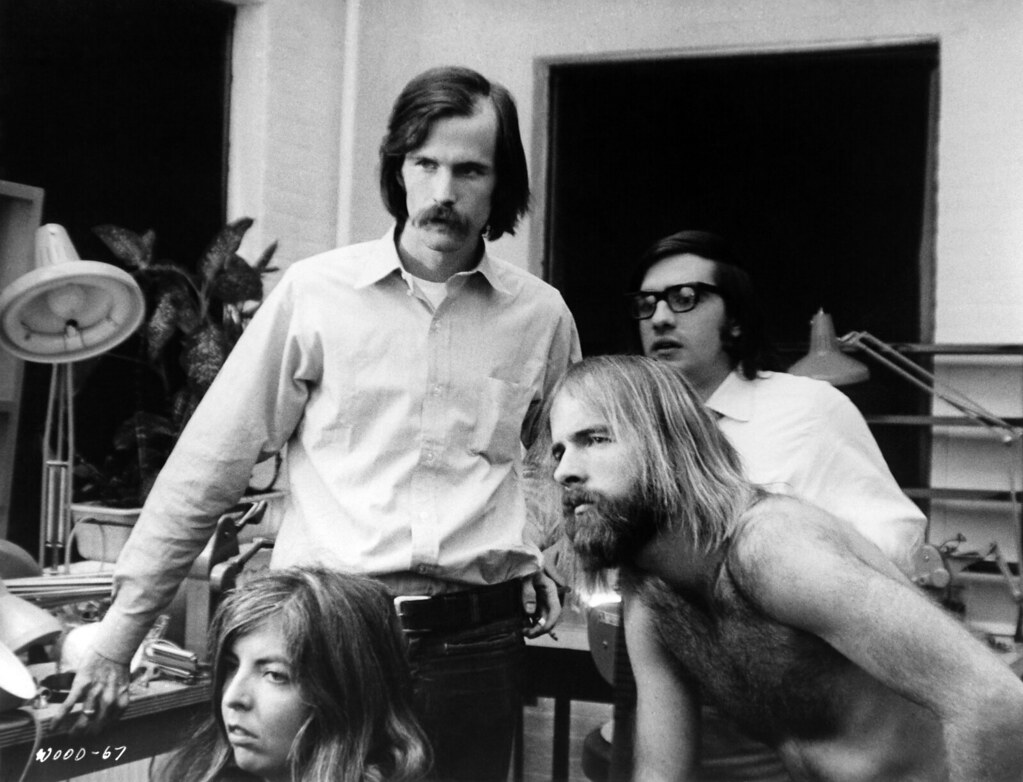

Throughout her Oscar-winning career, Thelma Schoonmaker has worked nearly exclusively with Martin Scorsese. And when people discuss the genius of Scorsese’s movies, they point to the comprehensive nature of his vision, and what that vision influences: the performance of the actors, the choice of locations, the set design, the selection of camera angles, the use of music to evoke mood. With a director whose vision is that clear, it’s easy to wonder what an editor like Thelma Schoonmaker can bring to the film. To understand, one needs to start with director John Huston’s explanation of editing. When asked during an interview what the purpose of editing was, Huston gave the following instructions to the reporter:

Look at the nearest lamp in the room.

Now look at me.

Now look back at the lamp.

Now look at me.

As the reporter swiveled his head back and forth between Huston and the lamp, he finally blinked. Huston stopped the reporter excitedly and explained that his blink was the purpose of editing. That the reporter had watched Huston and watched the lamp without blinking, but was willing to blink as his head swiveled. The willingness to blink during the swivel was an implicit statement that there was nothing of merit “in between”. Huston’s analogy was that editing was the process of knowing what shots and what information were worthy of the gaze, and what shots were “blinks” and deserved to be cut. It’s a solid analogy, and indicates a required empathy on the part of the editor – a knowledge of what a viewer might want from the story.

But Thelma Schoonmaker’s editing skills run deeper than that. I’d offer this take on Huston’s test:

Look at the nearest lamp in the room.

Keep looking.

Keep looking.

Keep looking.

Keep looking.

And so on…

One thing we notice in the length of a gaze is how our feelings about the lamp change, out of necessity. In the first few seconds, we register the site of the lamp, we recognize it as a lamp, and our brains process it in the context of everything else we’re looking at. To a functional, workmanlike editor, once that process of recognition and classification is done, the shot is cut. But when we don’t look away, our perceptions change. We go through the moment of curiosity (“Why am I not looking away?”), and then we either turn away in boredom or we begin to look for more depth. We consider the intricacy of the lamp’s design. We notice scuffs in its exteriors and we wonder where they came from. I recently read an axiom that said, “Everything is beautiful. Pay closer attention.” when faced with a lengthy gaze at the lamp, we are afforded the opportunity to consider beauty we would have missed if we had “blinked” right away.

This is not to say Thelma Schoonmaker focuses on long shots. (The helicopter scene in GoodFellas is evidence enough against that argument.) Thelma Schoonmaker’s strength lies in knowing exactly how many seconds she can hold a shot and allow us to consider it with some depth, and how many seconds will lead to boredom and disconnect. In her finest moments, it seems like the difference is in a single frame or two – 1/30th of a second. No other editors would allow a shot to go that far, to push the boundaries of boredom or disconnect. Similarly, there are hundreds of mafia movies in the existence, yet few of them have connected with audiences as strongly as GoodFellas, Casino, and Mean Streets. Certainly, editing is not the only component in that connection. The actors are amazing; but even the most accomplished actors (DeNiro, for example) are remembered more for their Scorsese movies than any others. We connect with the characters, no matter how horrible their actions may be.

Reviews of The Wolf of Wall Street, Scorsese and Schoonmaker’s nineteenth collaboration, comment on how the film’s two hour and forty minute runtime flies by. We sit through nearly three hours of characters because Thelma Schoonmaker is silently guiding us to a depth and understanding that other editors would never be brave enough to seek.