WALTER HILL: Born January 10, 1942

Originally published January 9, 2015.

Years ago, a group of friends and I left a party in the middle of the night. One of our friends had lagged a few seconds behind, and the rest of us walked down the block and piled into my car. I started the car and headed back towards the party to pick him up. In the minute or two it had taken to get to the car and get back a block, he had left the party, crossed paths with two strangers, and when we found him he was being held from behind by one guy, while another man brutally pummeled his face. Before I could stop the car, a friend in the backseat had jumped out to help. My friend ran up to the fight, and the puncher immediately turned and punched him hard in the face. The attacker then went back to throwing punches at the first friend. I stopped the car, and another friend and I climbed out. I don’t know if the attackers were concerned about a four-on-two fight, or they’d just grown bored, but they yelled a few threats and stormed off. In the end, two of my friends were bleeding (one severely). The entire thing took less than a minute. The thing that’s striking about random violence in real life is how ugly it is. The attackers threw wild, clumsy cheap shots. My friends had seemingly no ability to defend themselves outside of cowering. When we kept asking the first victim what precipitated the incident, he swore he had no idea. Life just went from celebratory and pleasant to escalated, brutal, screaming, hysterical, and bloody – in a few seconds. Real life battles are far from glamorous or linear; they’re random and awkward. They create more questions than they resolve. They’re unlike the movies, with clear heroes and villains and moral resolution. And few filmmakers have chased that unreal, clearly-moral universe like Walter Hill.

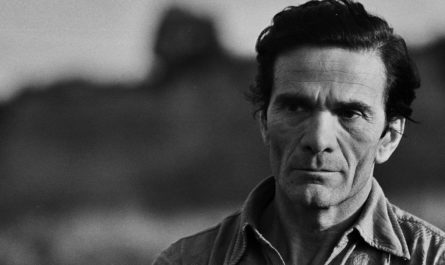

| warpic 1979 |

| The Warriors (1979) |

By the time I graduated high school, I was a huge Walter Hill fan. Near the end of my junior year, I went to the movies with a few friends. My friends went to see Lethal Weapon; I bought one of the only tickets to see Hill’s Extreme Prejudice, starring Nick Nolte and Powers Boothe. I had been waiting months to see it, and even the peer pressure of high school could not let me miss it. I’d seen The Warriors a few years earlier, and quickly began looking for all of Hill’s films and would go see his new releases as soon as they were released. At that point, he’d directed two street gang dramas, a Western, a war allegory, a boxing movie, a heist film, and an Eddie Murphy buddy-cop movie. All of the movies shared a very similar moral framework. Hill has always said that he only directs Westerns which don’t happen to be set in the west. His films are filled with good guys and bad guys, with no ambivalence about who is who. There are no anti-heroes in Walter Hill films, nor any vigilante confusion. His films are filled with heroic men and evil men, with no attempt to justify the motivations of either. Characters in Hill’s films simply are who they are, fully developed representations of a specific moral (or amoral) code.

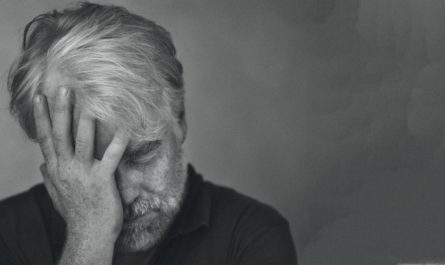

| soco pic 1981 |

| Southern Comfort (1981) |

It’s not an uncommon complaint that this world of heroic and evil men leaves little for women. Indeed, the women in Hill’s films are either props, background characters, or an extra prize that the hero and the villain are fighting over. It’s a fairly standard complaint about Westerns in general, and Hill doesn’t reject the complaint. He describes his films as “a stripped-down moral universe”, and in that universe, cinematic archetypes have been (and remain) generally male. The result of that stripped-down moral universe is the simple good vs. bad argument. But I think it’s misguided to assume that the creation of that universe is rooted in intellectual or moral laziness. Certainly, it must be an easier world to create. Unfettered by moral ambiguity and complexity of emotion, we presume that the intent of the film is to appeal to a base instinct, as if audiences are only seeking to be reassured that “good is good” and “bad is bad”. But we’re not. We understand that, even in the most morally/socially/emotionally complex films (though audience members may not agree over which character is good and which character is bad). The appeal of the stripped-down moral universe may not be due to a desire to view the world in a simplistic way, as much as it is a yearning for a simpler world.

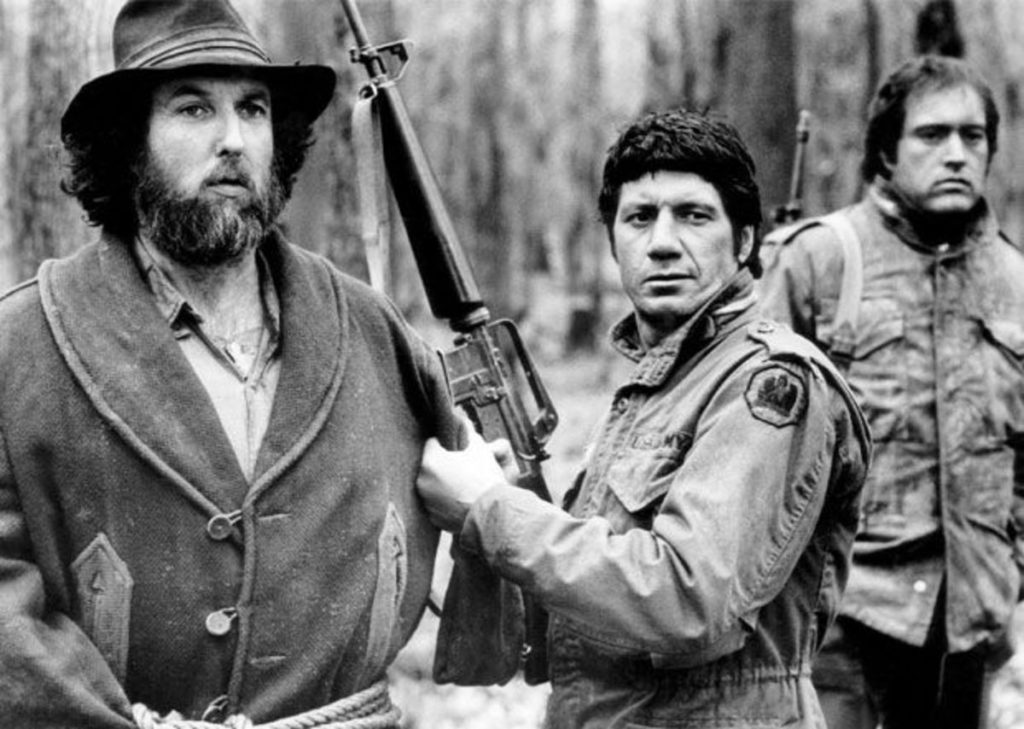

| ep pic 1987 |

| Extreme Prejudice (1987) |

We’re know that black-and-white thinking is a logical fallacy. We’re even aware that it’s a dangerous emotional pattern when we apply it to our thinking. Studies have shown that black-and-white thinking can lead to depression. The extreme thinking of an either/or, black-and-white world over-stimulates our emotions (“She’s so great!”, “He’s SO terrible!”, etc.), which inevitably crash from the wild fluctuations. And yet, we still lean heavily on this kind of thinking, as a culture. One only needs to look at the current political climate to see how much both sides of the aisle (not to mention independents) rely on black-and-white thinking to validate their party’s position. It may be tempting to label an adversary as “stupid” in an effort to explain why they rely on black and white thinking, but the more plausible reason is: certainty. As humans, we like certainty. We like the resolve of certainty, the lack of internal conflict. We like how an increase in certainty brings a decrease in vulnerability. Even if that certainty is logically flawed, we hold onto it desperately.

We like the films of Walter Hill, because it’s a world we wouldn’t mind living in. In that universe, the hero always wins. There is very little collateral damage in a Walter Hill film; it is just the moral hero trying to get the evil villain to stop what they’re doing. It ends in a showdown between the hero and the villain, which the hero always wins. Despite The Warriors being about a violent gang war in Brooklyn, there were no victims of violence aside from the heroes and the villains: no children shot by stray bullets, no beaten or killed accidentally. In fact, most of the film is stripped bare of background characters; Brooklyn is more like a gladiator ring than an over-populated borough. But there’s comfort and less vulnerability in stripping morality down like that. Contrast is a powerful tool, when used effectively. Walter Hill’s black-and-white world doesn’t look or behave like our richly-nuanced world with its shades of grey. (Roger Ebert once described it as “a ballet of stylized male violence”.) Hill’s cinematic world is blocky and starkly-contrasted; real life has – for most of us – too much depth and texture and shadow to even comprehend it all. Too much to understand why two men get beaten without explanation or recourse. Too much to understand why some stray bullets hit the wall and some hit an innocent victim. Too much to even be able to differentiate between the hero and the villain, sometimes. And we need that contrast. Shades of gray are defined by black and white, and so we occasionally need to retreat from the world of analyzing nuance (“Is this more white than black?”) and retreat to the ends of the spectrum, where the answers are simpler and we can take comfort in the idea of “right” and “wrong” not only as theoretical concepts, but as something to experienced. We shouldn’t live there (and can’t… at least not happily, amongst other humans), but an occasional retreat can sometimes be restorative. That was what Walter Hill excelled at; providing audiences with moments of clarity in an otherwise complex existence.

_________________________

External Links:

- Looking back at Walter Hill’s Southern Comfort, an essay on my favorite Walter Hill film

- Roger Ebert’s reviews of many Walter Hill films

_________________________

Years ago, a group of friends and I left a party in the middle of the night. One of our friends had lagged a few seconds behind, and the rest of us walked down the block and piled into my car. I started the car and headed back towards the party to pick him up. In the minute or two it had taken to get to the car and get back a block, he had left the party, crossed paths with two strangers, and when we found him he was being held from behind by one guy, while another man brutally pummeled his face. Before I could stop the car, a friend in the backseat had jumped out to help. My friend ran up to the fight, and the puncher immediately turned and punched him hard in the face. The attacker then went back to throwing punches at the first friend. I stopped the car, and another friend and I climbed out. I don’t know if the attackers were concerned about a four-on-two fight, or they’d just grown bored, but they yelled a few threats and stormed off. In the end, two of my friends were bleeding (one severely). The entire thing took less than a minute. The thing that’s striking about random violence in real life is how ugly it is. The attackers threw wild, clumsy cheap shots. My friends had seemingly no ability to defend themselves outside of cowering. When we kept asking the first victim what precipitated the incident, he swore he had no idea. Life just went from celebratory and pleasant to escalated, brutal, screaming, hysterical, and bloody – in a few seconds. Real life battles are far from glamorous or linear; they’re random and awkward. They create more questions than they resolve. They’re unlike the movies, with clear heroes and villains and moral resolution. And few filmmakers have chased that unreal, clearly-moral universe like Walter Hill.

By the time I graduated high school, I was a huge Walter Hill fan. Near the end of my junior year, I went to the movies with a few friends. My friends went to see Lethal Weapon; I bought one of the only tickets to see Hill’s Extreme Prejudice, starring Nick Nolte and Powers Boothe. I had been waiting months to see it, and even the peer pressure of high school could not let me miss it. I’d seen The Warriors a few years earlier, and quickly began looking for all of Hill’s films and would go see his new releases as soon as they were released. At that point, he’d directed two street gang dramas, a Western, a war allegory, a boxing movie, a heist film, and an Eddie Murphy buddy-cop movie. All of the movies shared a very similar moral framework. Hill has always said that he only directs Westerns which don’t happen to be set in the west. His films are filled with good guys and bad guys, with no ambivalence about who is who. There are no anti-heroes in Walter Hill films, nor any vigilante confusion. His films are filled with heroic men and evil men, with no attempt to justify the motivations of either. Characters in Hill’s films simply are who they are, fully developed representations of a specific moral (or amoral) code.

It’s not an uncommon complaint that this world of heroic and evil men leaves little for women. Indeed, the women in Hill’s films are either props, background characters, or an extra prize that the hero and the villain are fighting over. It’s a fairly standard complaint about Westerns in general, and Hill doesn’t reject the complaint. He describes his films as “a stripped-down moral universe”, and in that universe, cinematic archetypes have been (and remain) generally male. The result of that stripped-down moral universe is the simple good vs. bad argument. But I think it’s misguided to assume that the creation of that universe is rooted in intellectual or moral laziness. Certainly, it must be an easier world to create. Unfettered by moral ambiguity and complexity of emotion, we presume that the intent of the film is to appeal to a base instinct, as if audiences are only seeking to be reassured that “good is good” and “bad is bad”. But we’re not. We understand that, even in the most morally/socially/emotionally complex films (though audience members may not agree over which character is good and which character is bad). The appeal of the stripped-down moral universe may not be due to a desire to view the world in a simplistic way, as much as it is a yearning for a simpler world.

We’re know that black-and-white thinking is a logical fallacy. We’re even aware that it’s a dangerous emotional pattern when we apply it to our thinking. Studies have shown that black-and-white thinking can lead to depression. The extreme thinking of an either/or, black-and-white world over-stimulates our emotions (“She’s so great!”, “He’s SO terrible!”, etc.), which inevitably crash from the wild fluctuations. And yet, we still lean heavily on this kind of thinking, as a culture. One only needs to look at the current political climate to see how much both sides of the aisle (not to mention independents) rely on black-and-white thinking to validate their party’s position. It may be tempting to label an adversary as “stupid” in an effort to explain why they rely on black and white thinking, but the more plausible reason is: certainty. As humans, we like certainty. We like the resolve of certainty, the lack of internal conflict. We like how an increase in certainty brings a decrease in vulnerability. Even if that certainty is logically flawed, we hold onto it desperately.

We like the films of Walter Hill, because it’s a world we wouldn’t mind living in. In that universe, the hero always wins. There is very little collateral damage in a Walter Hill film; it is just the moral hero trying to get the evil villain to stop what they’re doing. It ends in a showdown between the hero and the villain, which the hero always wins. Despite The Warriors being about a violent gang war in Brooklyn, there were no victims of violence aside from the heroes and the villains: no children shot by stray bullets, no beaten or killed accidentally. In fact, most of the film is stripped bare of background characters; Brooklyn is more like a gladiator ring than an over-populated borough. But there’s comfort and less vulnerability in stripping morality down like that. Contrast is a powerful tool, when used effectively. Walter Hill’s black-and-white world doesn’t look or behave like our richly-nuanced world with its shades of grey. (Roger Ebert once described it as “a ballet of stylized male violence”.) Hill’s cinematic world is blocky and starkly-contrasted; real life has – for most of us – too much depth and texture and shadow to even comprehend it all. Too much to understand why two men get beaten without explanation or recourse. Too much to understand why some stray bullets hit the wall and some hit an innocent victim. Too much to even be able to differentiate between the hero and the villain, sometimes. And we need that contrast. Shades of gray are defined by black and white, and so we occasionally need to retreat from the world of analyzing nuance (“Is this more white than black?”) and retreat to the ends of the spectrum, where the answers are simpler and we can take comfort in the idea of “right” and “wrong” not only as theoretical concepts, but as something to experienced. We shouldn’t live there (and can’t… at least not happily, amongst other humans), but an occasional retreat can sometimes be restorative. That was what Walter Hill excelled at; providing audiences with moments of clarity in an otherwise complex existence.