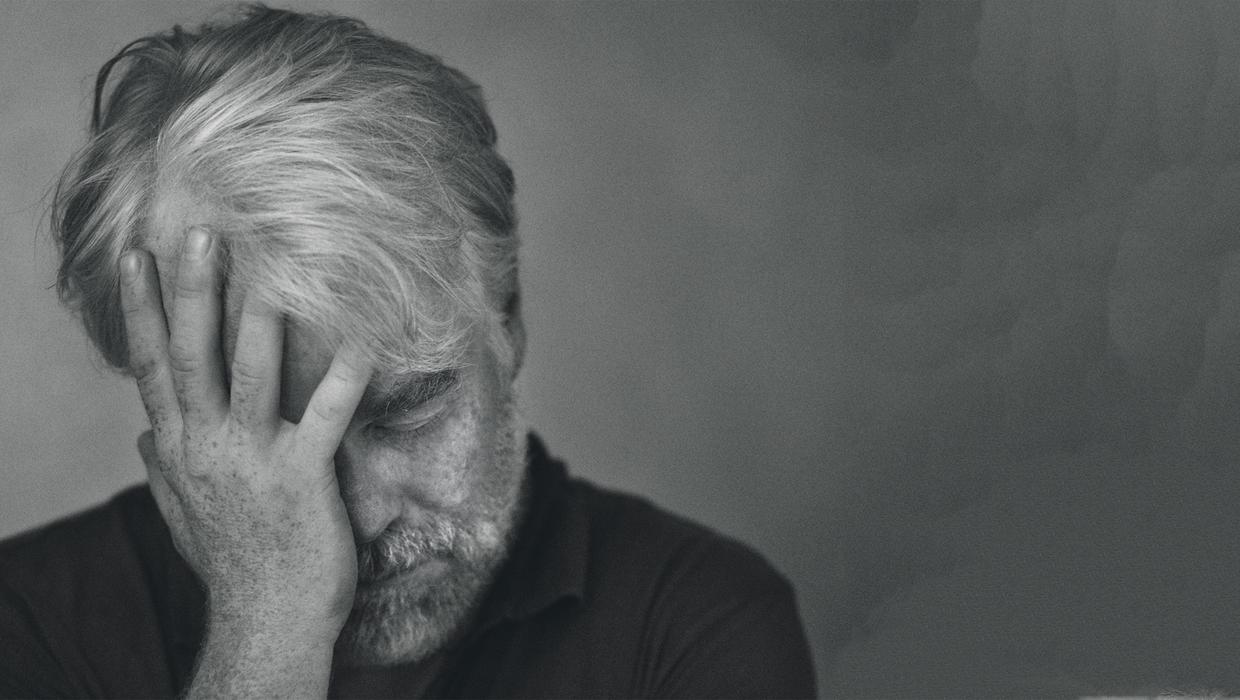

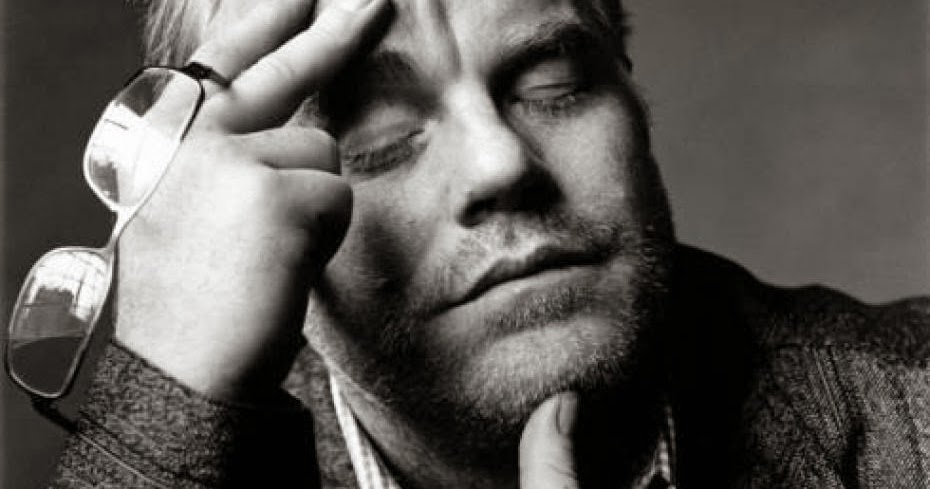

Philip Seymour Hoffman: July 23, 1967 – February 2, 2014

When I heard the sad news that Philip Seymour Hoffman had died, I immediately flashed to a bunch of different roles of his that I loved. As the roles I could remember him in unfolded in my mind (always met with an “Oh, he was amazing in that!”), I kept going back to a single scene of his in Boogie Nights. The role of Scotty in Boogie Nights seemed almost the personification of Hoffman. He was, by all accounts, not someone we would think of as a leading man, or a star. He was paunchy. He mumbled. He had a hang-dog face. And yet, by sheer force of talent, he became a leading man, an Academy Award winner, a darling of Broadway whose Willy Loman would be considered as good as Lee J. Cobb’s or Dustin Hoffman’s. And as Scotty, he seemed similarly the round peg trying to fit into the square hole. He was the chubby, pasty man-child with no self-confidence dropped smack-dab in the middle of a world of hyper-sexuality and gorgeous tanned bodies. And he works his way into the inner circle through his unwillingness to be told he doesn’t belong. It’s Scotty’s curse, really; something in him is so desperate for acceptance that he’ll take abuse and grunt-work and being ingored or insulted. And so he stayed. The moment that was so powerful was after he attempted to kiss Dirk Diggler and was rejected. Scotty’s reaction was so brutally raw and tortured. His reaction was self-loathing. Which, when you think about it, is ridiculous. To assume that a hyper-sexual friend who makes his living having sex with strangers might be willing to have sex with you is not entirely far-fetched. But Scotty’s realization is deeper. It’s a realization that, once again, he has taken the initiative to ask that someone accept and love him, and he’s been denied. Again. In a few seconds, we see an entire life laid bare before us, a life of constant rejection and unworthiness, and the utter torture of realizing that your belief that things have changed is all a facade. Life has a way of repeating itself for some people, and in that moment, Scotty was witnessing the darkest parts of his life, which he’d worked to avoid, reappear and claim their territory on his soul. Something about the moment felt – from the outside – like the most representative moment of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s life.

I sense that life is too complex and too filled with painful interactions and accidental losses for most of us. It’s the nature of an existence on a crowded planet filled with creatures whose primary survival instincts get played out in often selfish and hurtful ways. Some people are able to accept that reality and flow with it. But some of us seem destined to continually be shocked by it, and to need coping mechanisms that don’t solve the problem, they simply remove us from the equation. We become addicted to drugs or booze or sex or money. We focus our brains on this obsession to the point that it tunes everything out and makes our existence laser-focused, barreling through the people who might hurt us first, if only we’d given them the chance. Or we go the other way and lose ourselves completely in other people until we can no longer feel anything on our own, and remain awash in the decisions of others. The spectrum is wide, and the paths very immeasurably, but the results are always the same; “I will focus on this until I can forget about the pain.”

I’m not going to try to armchair quarterback Philip Seymour Hoffman’s death, and pretend I know enough facts to suggest what he could have done differently. I’m not going to pretend I have any answers at all. All I know of the situation is that a man who – from the outside – had plenty to live for was sober for over two decades and suddenly fell so deeply into addiction that it killed him. Aaron Sorkin eloquently pointed out that Hoffman died from heroin, not simply from a heroin overdose. To pretend that it was simply “too much” heroin is to deny the greater issue of addiction and its constant pull. Addiction works like so many emotional issues; we learn to live a better life with this potential demon within us – a demon which patiently, insidiously lies dormant until the opportunity arises to re-appear and wreak havoc upon our world. Hoffman had gone to rehab in his early twenties; that demon would wait nearly 25 years to re-appear. And it killed him.

But they are not always deadly. There are times when the demons that hold us down become too much for us, and if they haven’t managed to kill us, we simply… change. In an instant. In a single moment, we change from “alcoholic” to “in recovery”. We hit rock bottom and our self-loathing stops and almost inexplicably we’re caring for ourselves. We have one fight to many and our relationship status changes to “single”, or we finally stop throwing up roadblocks and almost immediately fall in love. Change, we find, is remarkably easy. It’s getting to the point where we’re ready to change that is difficult and depressing and (at times) deadly. But when we hit rock bottom, we change. Because we have to. Because there truly, genuinely is no place left to go. And finding a new direction when you’re backed into a corner is not only easy, it’s the only option outside of “giving up and dying”. And so we change. Our lives get altered. We feel better, or least we feel different. And we move in the new direction. But we do so without ever knowing the underlying reasons for our previous behavior. Never knowing why we did what we did, or how we ended up there. Never knowing the path we took, and not knowing how to avoid it in the future.

There is a difference between “change” and “resolution”. Too often in life, we move in a new direction after we can go no further in our previous direction. And while we’re moving and we feel better, we’re no less lost than before. Yes, we’re moving ahead, but with as little direction as before. Those periods are a fertile ground for unresolved issues to bloom into new problems. Sometimes we’re lucky and the new problems never manifest themselves. Or they may arrive with less intensity than before. Or perhaps they take decades to re-surface. Either way, they’re within us, temporarily dormant, but developing beneath the surface like a locust larvae.

A death like Phillip Seymour Hoffman’s – not to mention the couple of years of relapse and the final months of complete strung-out binging – forces us to consider our current directions. Is the path we’re on a path that we have chosen, or are we merely moving forward from the corner we had been previously backed into? Because it’s easy to forget that we’re “unresolved” when we’re finally feeling less stress, but “less stress” is not the same as “at peace”. And if we can’t acknowledge that, we march ourselves – gleefully, ignorantly – into the next corner. Ideally, resolving our issues acts as a map for our soul which keeps us from repeating those “fight-or-flight” situations. Without that resolution, without those maps, the well-worn paths of habit lead us right back to those demons. It may take 25 years, but eventually, we’re likely to find our demons returning.