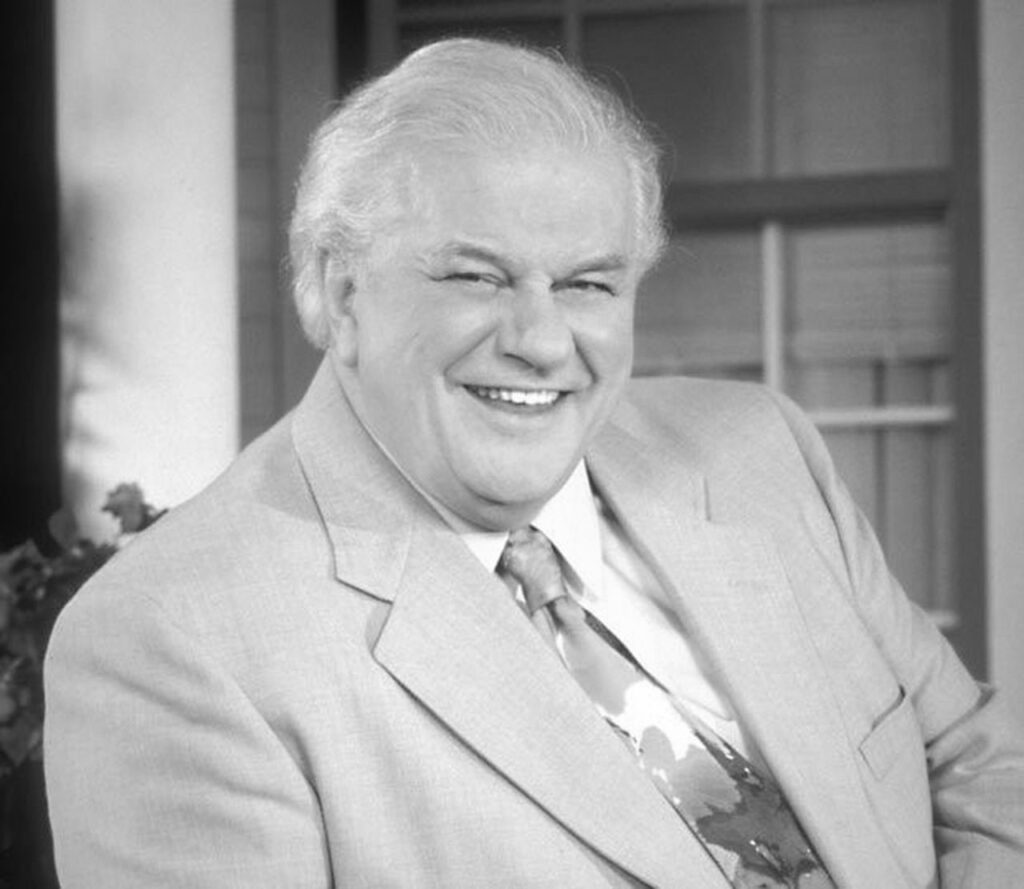

CHARLES DURNING: February 28, 1923 – December 24, 2012

Despite all that I post here about artists, athletes, and historical figures, the person I’ve probably been most influenced by (and most closely model my life after) is my grandfather. A post-World War I baby, he left school as an early teen to help his family out during the Great Depression. A few years before he died, he wrote out some of the details and a few stories from his life; the contrast between the grim realities of the stories and the almost detached way he spoke about them is startling. He told tales of earning meals by killing rats in a hotel kitchen; the more he killed, the more food they would give him – cooked in the same infested kitchen in which he had just bludgeoned vermin. He talked casually of being left alone for a night in a train station to wait for the next morning’s train – at age 6. Despite his lack of formal education, he became very well-educated in the focused way that most self-taught people are. He learned how to run a business, how to manage people, how to leverage debt, and manage risk. He knew the stock market and tracked his savings and earnings every day in a large financial ledger. Near the end of his life, we would watch Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? together and he was regularly puzzled at the level of trivia in my head. To him, knowing who wrote most of Glen Campbell’s hit records or who played shortstop for the ’82 Brewers was a luxury he couldn’t understand. Knowledge to him was about moving yourself forward. The mountains of useless information in my head (the answers are Jimmy Webb and Robin Yount, by the way) were completely foreign use of time to him. It was a luxury that I have in part because of the life he helped to give me. And while I may have had a much easier upbringing, I learned from him one lesson: that hard work is a sort of salvation.

I once read a quote that said, “Don’t be upset about the things you didn’t get from the work you didn’t do.” I’m not sure who said it originally, but it could have been my grandpa. In honesty, it could have been a lot of people my grandpa’s age. This is not to say that hard work will always get you what you want; it just means that not working makes those odds nearly impossible. And so he worked. Like so many of that generation, he worked. He worked long hours every day. He worked weekends and nights and holidays. He worked until the work was done and never played the “9-to-5” game. It was a lesson that I picked up on and found myself gravitating to as I got older. Work became a salvation for me, and I realized that I could overcome a lot of deficits by simply outworking everyone around me. If it meant staying awake for three days straight, so be it. “Work hours” be damned; if my grandfather and his generation could do it, so could I. One member of his generation whom I also admired very much was actor Charles Durning. Durning shared many similarities with my grandfather, and it was his thoughts on those similarities that I found particularly eye-opening.

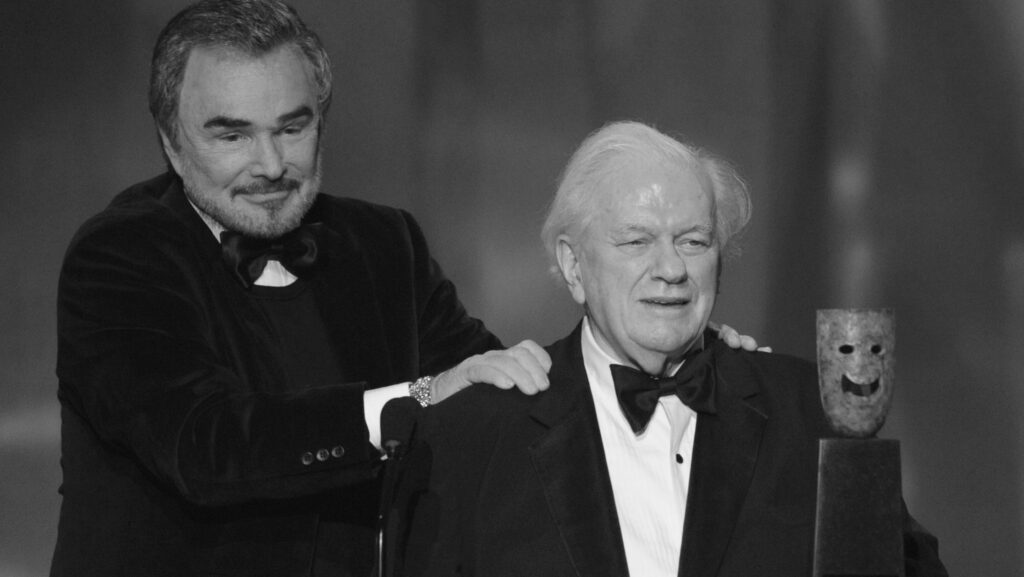

Durning was born in Highland Falls, New York in 1923, a few years after my grandfather. Durning’s father had been mustard-gassed during World War I, and the physical and psychological effects had confined him to his bedroom for the rest of his life, where he would scream and shout at constant pains, invisible enemies, and frequent nightmares. Occasionally, he would leave the room to physically attack Durning, his mother, or one of his siblings. By the time his father passed in 1935, five of Durning’s nine siblings had also died of scarlet fever or smallpox. After making a living after high school as a dance instructor and boxer, he was drafted into the US Army in 1943. He completed basic training and boarded the Queen Mary to go to Europe to fight. (Also on board was an enlisted man 17 years his senior, Burt Reynolds, Sr., whose son would later become an actor and one of Durning’s best friends.) Durning’s first moment of combat? June 6, 1944. The invasion at Normandy.

When the gates of the transport boat opened to allow the soldiers to exit, the man directly in front of Durning was shot and killed. Soldiers behind him pushed their way forward, and Durning was thrown into the water. The man directly behind Durning was shot and killed. Durning dropped into 60 feet of water with a 60-pound pack on his back and immediately sank. He shook off the pack, his helmet, and rifle and swam to shore. The carnage continued for hours. In the end, he was the only survivor of his unit that day. A week later, he was injured in a landmine explosion and briefly recovered in London when all soldiers were required to leave the hospitals to combat the German Ardennes offensive. In Germany, he was attacked by a soldier so young Durning couldn’t bring himself to shoot the boy. The young German soldier sliced him repeatedly with a bayonet, and they fought hand-to-hand until Durning realized the German simply would not stop until one of them was dead. Durning found a large rock and beat the soldier to death, then held him in his arms and wept.

Durning was released from duty in 1946. He had earned a Silver Star, a Bronze Star, and two Purple Hearts, but he never advanced past the rank of Private First Class. He moved to New York and taught dance lessons and took small-time fights for money while he took acting lessons. Within a few years, he was working in burlesque houses and acting in off-Broadway productions. Joseph Papp of The Public Theater discovered him in 1961 and added him to the repertory of the New York Shakespeare Festival. He would go on to perform in 35 NYSF productions as his film and television credits began to roll in. By the time he died, Durning had acted in over 200 film and TV roles. And he took great pleasure in it. Despite a career primarily playing authority figures and corrupt jerks, he could also be warm and funny; he played Santa Claus no less than five times in his career. Co-star and close friend Joe Mantegna described Charles Durning’s work ethic in terms that remind me of my grandpa:

Charlie was only happy when he was working. The best job for Charlie was the next job. I mean, his body of work speaks for itself.

Durning, on the other hand, had a more personally reflective take on the appeal of acting for him. In a 1983 interview with Parade Magazine, he admitted:

There are many secrets in us, in the depths of our souls, that we don’t want anyone to know about. There’s terror and repulsion in us, the terrible spot that we don’t talk about. That place that no one knows about — horrifying things we keep secret. A lot of that is released through acting.

It’s the kind of thing that underlies much of what I’ve been writing and thinking about for recent years. All of us have histories that we have to reconcile, and those histories can sometimes be too traumatic or too overwhelming to deal with, whether it’s dramatic (like poverty or war) or just an everyday emotional scenario we’re not equipped to process. These things incite us and inspire us to process them in whatever way we can. For my grandfather, it was work. For Durning, it was acting. Would it be smarter/wiser/better to just process these experiences and not have to sublimate them into some other effort? Of course. Is “having great art” or “building a great business” worth the cost of carrying these unresolved psychological complexities around for a lifetime? Probably not. But it certainly beats many of the other options. (Look to Durning’s father for a good counterpoint.) And the fact is, while The Greatest Generation may be an obvious example, every single human goes through this process in their life.

The aspects of Charles Durning – and my grandfather – that I admire so much are characteristic of their generation. They were a generation raised under the effects of global violence and massive poverty and were greeted into adulthood with World War II. All of this occurred in the nascent days of human psychology when feelings were not things to be discussed openly, if at all. There could be no less-optimal scenario for emotional health. But instead of collapsing on top of themselves, they found ways to process that life into productive results. And healing. Sometimes salvational. It may not be perfect, but at least it’s a step in the right direction. In the case of many from that generation, it was a lifetime of steps in the right direction.

The day my grandfather died, I was visiting him in the hospital. We both knew the end was very near. I sat with him for a while, and I got up to leave. I had to be at work that afternoon, and I knew he would be very upset if I missed work to sit with him. We rarely said the words, “I love you” very often to each other, and certainly not since I reached adulthood. But I never questioned the man’s undying love for me, which he had shown me for the entire 30 years I’d been alive. As I walked to the door, I knew it would be the last words we ever spoke.

“I love you,” I told him.

“Go to work,” he replied.

It was the most loving send-off I’ve ever received.