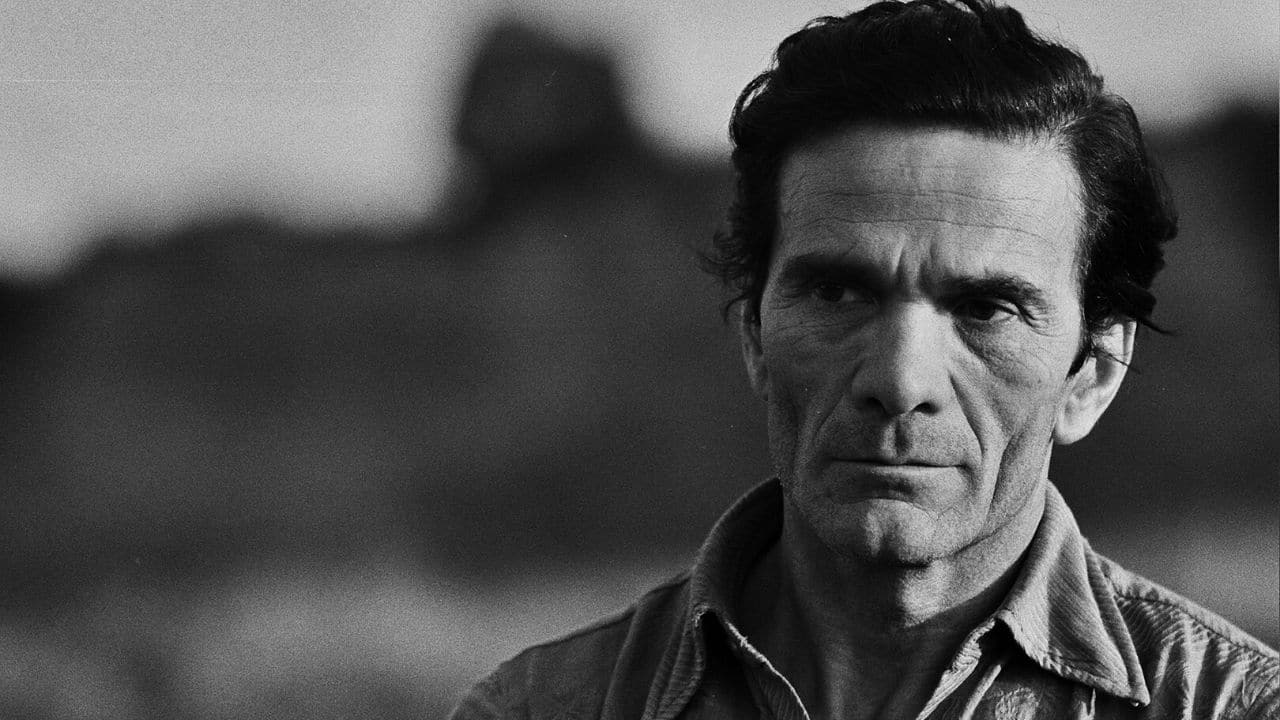

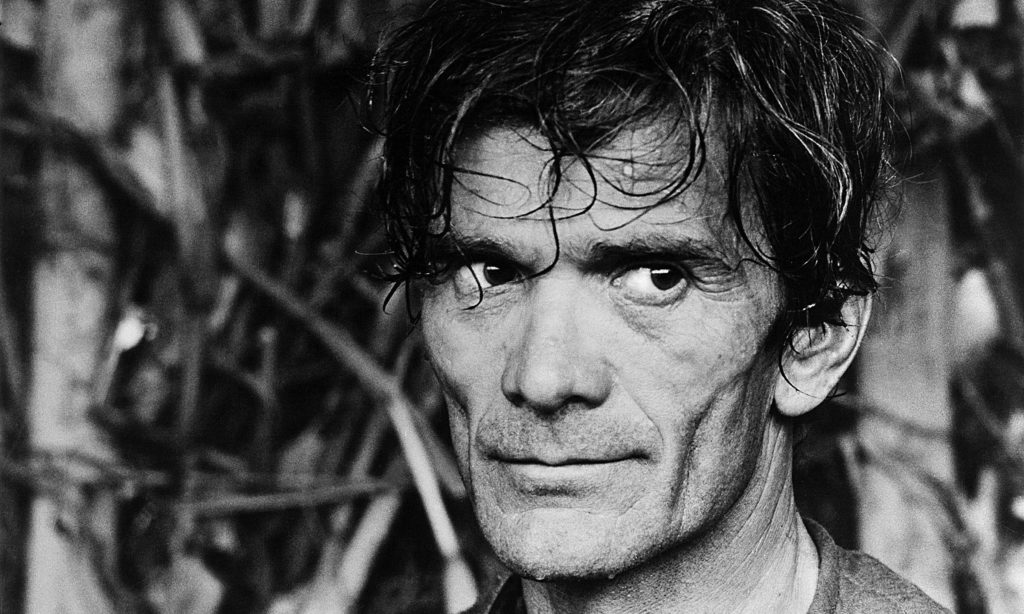

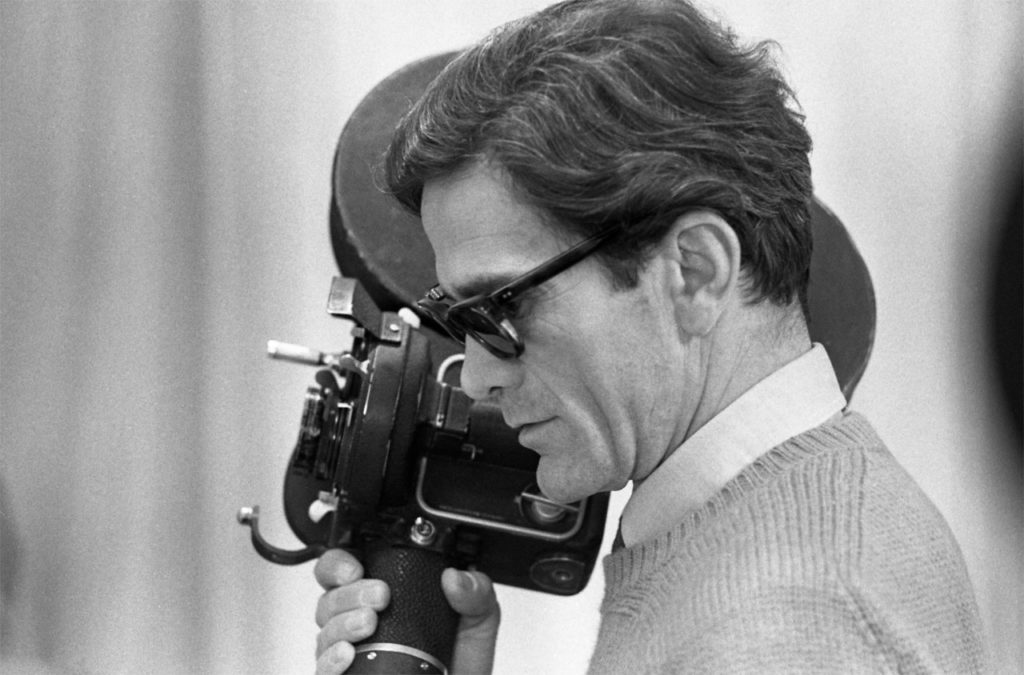

PIER PAOLO PASOLINI: March 5, 1922 – November 2, 1975

I don’t post on Facebook very often, but every time I do, I have a moment before I hit the “Post” button where I have to stop and think about the intended audience for the post. If the post is aimed at my biker friends, will it confuse my progressive liberal friends? If it is aimed at my religious friends, will it confuse my secular or atheist friends? If it is about art, will it bother people who know me as a down-to-earth guy? Will something work-related confuse everyone else who doesn’t understand what I do, or what goes into my job? All of us play different roles, but in many cases, we’re the same person working multiple roles. Many people are the same person in their role as “son” as they are in their role as “co-worker”. Move between roles with some people, and there will be no surprises. I am not one of those people. In my life, I am more of a chameleon, moving between groups and roles and changing to accommodate each role. And blending or overlapping those roles is difficult, because the person I am in each role is very different from the person I am in other roles. This is not to say I’m wishy-washy or simply wearing a costume. My adoption of my roles is not haphazard or surface-level. But they are wildly different roles with dramatically different types of people – people who would not normally get along. At all. And there are people who can manage this kind of “broad spectrum” of living without changing themself a bit. But it’s a difficult road to manage, because it’s easy to alienate people. Which is what happened when an devout Catholic, Marxist, openly homosexual leftist who sided with working-class police over progressive students threw himself into art.

Pier Paolo Pasolini was seemingly born to be an artist. The son of a military officer (who would save Mussolini’s life during an assassination attempt when Pier Paolo was four) and a school teacher, Pasolini was the product of multiple influences. He was writing poetry (citing Rimbaud as an influence) by age seven. As Italy grew into a fascist state, Pasolini developed as an artist. He continued to write poetry, but also became a political activist. He tried his hand at journalism. He studied philology philosophy, and linguistics. By the 1950s, Pasolini was a teacher who wrote and published as often as possible. He eventually took work writing dialog for Federico Fellini’s film Le notti di Cabiria. He would begin shooting his own films in 1961, at age 39. At this point, Pasolini was firmly entrenched in Communist politics. But he was also devoutly Catholic. Similarly, he maintained a certain nostalgia for pre-war Italy, the belief that the war had introduced a consumerism to Italy that would destroy its soul. And so Pasolini decided to make films, mostly with genuine, non-acting Italians, and speak to these seemingly-contradictory beliefs that he held.

My first experience with Pasolini’s films was his second film, Mamma Roma. In the film, the titular character Mamma Roma is a former prostitute who plans on giving up her career to peddle fruit in the market. She has a teenage son that she had sent away, so he wouldn’t have to witness her work, and now that she intended to become a legal worker, she wanted her son with her. The son, played by a non-actor, returns to the new post-war Rome, which is a town of decadence and consumerism. Centuries-old architecture is now compromised by chewing gum and Coca-Cola ads. In the middle of this, Mamma Roma’s son finds out what his mother has been doing for years, and it destroys him. He begins hanging around with a crowd of disaffected, troubled youth. He eventually steals a radio and goes to prison, where he is stripped to his underwear and tied to a table with his arms outstretched in a clearly Christ-like pose. In this pose, the son dies. Outside of the prison, when she hears of her son’s death, Mamma Roma goes to her apartment intending to kill herself by jumping from her apartment window. Before she can jump, she sees the dome of the local basilica, and she stares at it. Pasolini uses reverse shots, normally reserved for close-up conversations, in the back and forth between Mamma Roma and the dome of the basilica, which rises above the cityscape. The two continue their silent conversation, and the film ends.

Within all of the seemingly-contradictory beliefs Pasolini held, one thing is constant: Pasolini believed that a certain sickness had entered the soul of Italy, and it threatened to destroy them from within. Unlike other politically-leaning films of the time, the son in Mamma Roma does not become a criminal because of external poverty or overt need. He becomes a criminal because his moral character has been crushed by his mother’s lack of moral character. When he dies in prison, he doesn’t die at the hands of brutal guards or as the result of political motivation. He dies because his soul is destroyed by a moral decay. And when his mother tries to kill herself (she the victim of lost hope), she gets stopped and locked in battle with the invisible power of the church and God. Mamma Roma, like most of Pasolini’s films, suffered from Pasolini’s problem of being able to relate to so many different groups, but not being able to cross over. It was a pro-Catholic, pro-church film that was eventually boycotted by the church for foul language and sexuality. It was a pro-Marxist film that was never directly condemned the state. This isn’t necessarily the fault of Pasolini; he was merely speaking through his muse. The problem was with his muse, which was too broad and touched too many people in too varied a set of circumstances that the films seemed to impress and insult, in equal measure.

When Pasolini died in 1975, it was at the hands of a seventeen-year old male prostitute. The official story was that the teenage boy had been paid for sex, and when Pasolini got rough with him, he beat him to death and then ran over him with Pasolini’s own car to kill him. The teen was convicted, and almost immediately, the story seemed fishy. Years later, evidence would mount to suggest that Pasolini had been killed by anti-Marxists who had run over his body to hide the severity of the beatings (which could not have been administered by a single teen). Indeed, when his body was later discovered, it was so mangled that the woman who discovered it assumed it was garbage that had been dumped on her lawn. Either way, the death was undignified and undeserving and out of line with the direction he wanted his life to take. If the original story is true, a Marxist with a deep-seated worry for the decay of Italy’s soul died because a teen prostitute would not allow himself to be brutalized at Pasolini’s whim. If the other story is true, a man who fought for equality and redemption of the soul was martyred, and the powers within the country he fought so hard to save covered up the martyrdom to make him look like the victim of his own suppressed impulsestowards brutality and dominance.

There’s nothing wrong, per se, with having the kind of broad interests and passions that Pasolini held. In fact, the more broadly-held deep beliefs are, the more the person holding those beliefs is required to truly examine them, and re-consider them under the light of new influences. It’s too easy for a Marxist to deny the power and meaning of the church, or vice versa. It’s too easy to accept a single role for ourselves and adorn ourselves in that role’s belief system, whole-cloth. To never consider the intricacies within it which may allow for other beliefs to seep in and mesh with our current beliefs. To expand our belief system in ways others might consider unimaginable. And we don’t do that, often times, because of other people. People who share our roles and who adopt the beliefs of that role as immutable law, and consider any change to that a threat to their very existence under that role. You can not be a progressive and support gun rights, they say. You can not be a biker and a feminist. You can not be an artist and a white-collar worker. You can not be a homosexual and a Catholic. You can not be a Marxist and Catholic. According to a number of sources, Pasolini was murdered because of the threat his seemingly-divergent beliefs caused to others. Which is not to say he should have done anything different. But the broader we live our lives, the more we have to be aware of each step. The more we have to recognize that we became no longer accepted for who we are, but merely for the parts of who we are that agree with the person we’re communicating at that moment. It’s a fragmenting and confusing world, lived one highly-tailored Facebook post at a time.