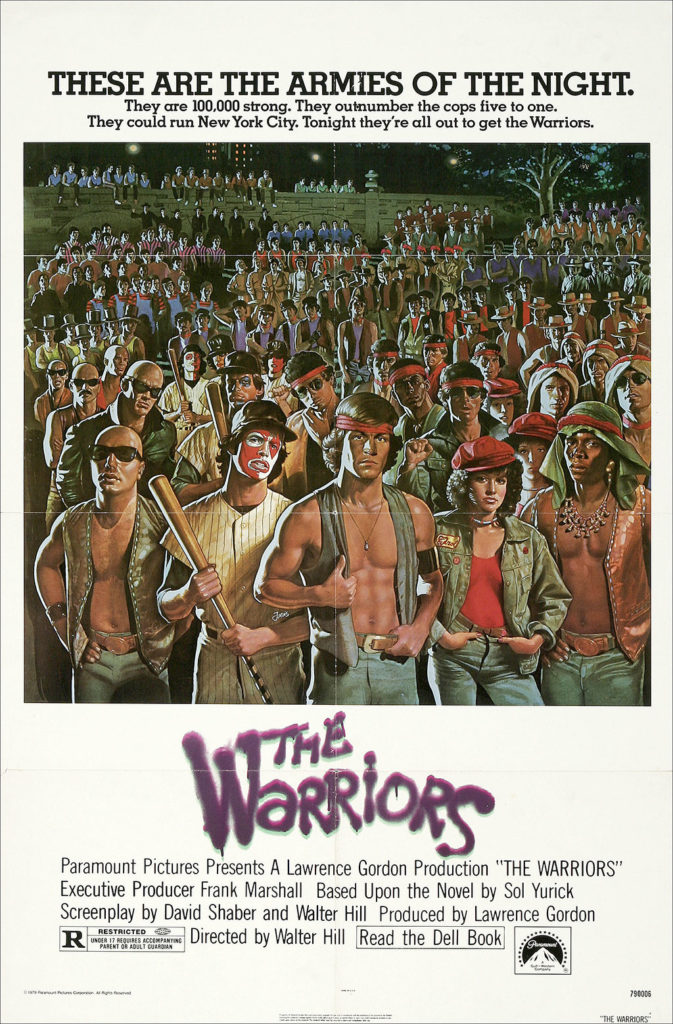

THE WARRIORS: Released February 9, 1979

Recently, my wife and I both experienced similar situations when hanging out with groups of male friends. In both situations, the groups of men all knew each other well and had spent plenty of time together. In both cases, a mutual friend stopped by and joined the gathering. In both cases, the newcomer was a strong “alpha male” type: masculine, assertive/aggressive, independent. The men attempted to integrate themselves into the groups immediately, as a confident male is wont to do. That’s when all hell broke loose. Suddenly, roles became unstable. Behaviors became amplified and assertive. Some behaviors became aggressive. In an instant, old relationships became unstable and the familiar roles became unfamiliar. Men were showing off for each other, passive-aggressive insults (masquerading as jokes) flew. When my wife experienced it first, I assumed it was something about males in the presence of a female. When I experienced it a few weeks later, there were no women present. This was a male thing – a masculinity thing. Ask most men about their feelings about masculinity and we don’t have much of an answer. In a patriarchal society, unfortunately, it’s not something men need to consider very often. When we do, it’s usually because masculinity is being indicted (or at least questioned), and the consideration is overloaded with defensiveness. And yet all of us have grown up in a world that constantly feeds us messages about masculinity and what it means. And one of the most extreme culprits in this process is cinema.

When Walter Hill decided to make The Warriors in 1978, he wanted to change it from the original novel. The 1965 source novel, written by Sol Yurick, was a modern-day re-telling of Anabasis, an heroic military journey told by Greek soldier and writer Xenophon. In Anabasis, Xenophon was part of an army of 10,000 Greek mercenary soldiers who had traveled deep into Persia to align with a prince (named Cyrus) who had plans to take the throne from his older brother. Cyrus was killed in an early battle, and the Greek army was now trapped deep in Persia and hunted by a vengeful and angry king and his armies. Yurick followed Xenophon’s tale very closely, but moved the entire tale to New York City and turned the regional armies into street gangs. It was a smart way to re-tell a story that some historians believe is one of the greatest adventure stories in human history. While Walter Hill appreciated the Yurick novel, he had no desire to make an historical allegory. Hill wanted to make a comic book movie (later “director’s cuts” of the movie would indeed include screen wipes of the film that looked like comic book pages). Hill wasn’t looking for accuracy; he was looking to stylize gang violence. And in doing so, The Warriors also becomes a touchstone for defining much about masculinity.

I was twelve when I saw The Warriors for the first time. A school friend had the first VCR I’d ever seen, and his parents allowed him to rent The Blues Brothers and The Warriors for a birthday party. I neglected to mention to my parents that I would be watching the film, and I was equal parts mesmerized and disturbed. I knew what I was watching was fascinating, and something inside of me recognized that even if I never traveled to New York, and even if I never joined a street gang, and even if I never got in a fight in my life, I would undoubtedly face some of the issues that The Warriors were forced to face as they fought their way back to Coney Island. I just wasn’t sure what issues I would face. Or when. Or how. But The Warriors seemed like a barely-definable glimpse into male adulthood, and so I was horrified by the close calls with the different gangs, the menacing stand-offs before the fights, and when Fox got run over by the subway car. (And David Patrick Kelly, whom is a phenomenal talent, has always been able to terrify me at will. His turn as Luther, the Rogues’ wildcard leader, was particularly nightmare-inducing for twelve-year old me.) I would go home after the party, and have so many nightmares that I ended up sleeping on the floor of my parents’ bedroom.

My mother explained that I had just been exposed to too much violence, but I knew it was more than that. The Warriors was my first exposure to pure masculinity. I’d had examples from the men in my life and from television, certainly, but The Warriors was nothing but masculinity. Of the few women in the movie, one was a prize for the winning gang, one was a victimized store clerk, one was an undercover cop (posing as a prostitute), and the rest were The Lizzies, a female gang every bit as masculine as the male gangs. For Hill, heightening that aspect to comic book levels was his goal. Instead of portraying street gangs as a social ill to be dealt with, Hill simply emptied the streets of New York of civilians. Throughout most of the film, the entire city of New York feels desolate and abandoned. The Warriors weren’t bad guys using their alpha male-ness to terrorize a city; they were merely guys from Coney Island, trying to get home. In Hill’s universe, gangs are simply expressions of social order. And so the battles between the gangs may feel like the hyper-masculine part of the film (despite having a serious “ballet” aspect to their choreography which actually made the violence – Fox’s demise aside – much less realistic and frightening), but in reality, they simply serve the larger masculine traits like independence, bravery, hierarchy, physicality, and assertiveness. The Warriors does not just rely heavily on these traits, those traits encompass everything in the film.

Because The Warriors is not a film that questions the “why”s behind masculinity. It never seeks to judge the men in the gangs for their masculine traits. While the post-sexual revolution America may have been considering the value and impact of gender differences, Hill’s films didn’t even acknowledge that debate. To him, masculinity as a set of gender traits was irrevocable. We could discuss it and work towards evolving it, but it’s not something to ever get “past”. Hill even recognized that masculinity was “precarious” (a term popularized in recent years); that masculinity is not a set of specific traits defined by a culture, but instead a series of traits defined by individuals within the culture. As such, masculinity is earned or achieved by an individual, based on their own competence in the masculine traits that matter to them. So a lyric poet may earn his masculinity based on his academic and verbal prowess, and not feel threatened by a high-school dropout MMA fighter. The Warriors were an example of that. They had one leader to set direction and settle decisions, but each one had an archetypal role: a brawler, an artist, a diplomat, a wildcard, etc. None better or worse than the other, none threatening to the others. Each had earned his precarious masculinity within the group, and fought alongside his brothers to retain it from the threatening outside world.

And this is what felt so threatening to a twelve-year old boy in the early stages of puberty. That “manhood” was a product of the traits of masculinity, that we needed to find those traits, and that the rest of our lives would be a fight to retain those traits – and by extension, our manhood. It felt threatening and terrifying (and in the case of Fox, deadly). And more than thirty years later, it clearly still feels threatening, because the introduction of a stranger into a defined group of precarious masculinity created chaos. Even today, the outside world is threatening. We spend our lives creating and defining tribes, only to find them disrupted and to find ourselves adrift as soon as we’re exposed to the unfamiliar. And while the film The Warriors embraced masculinity stylistically, the characters The Warriors embraced it out of necessity. Masculinity is just a part of life, and for those who live within its confines, we need to learn to accept – or at least acknowledge – its precariousness. Yes, we can hope to mature and evolve the traits, softening its more damaging edges. But it will always be here. And films like The Warriors help to expose that world, and to acknowledge that, like The Warriors, we’re out here ceaselessly trying to make our way home, always one small change away from total collapse.