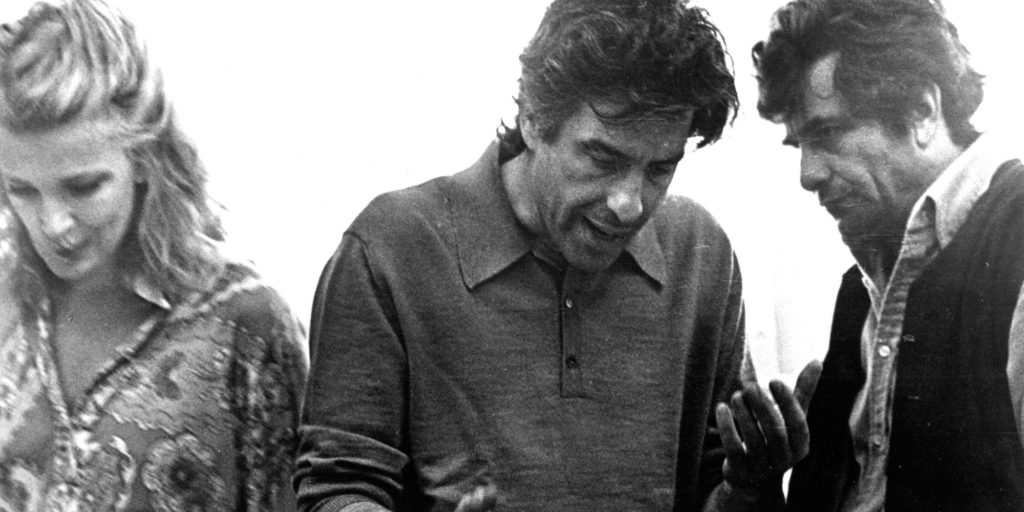

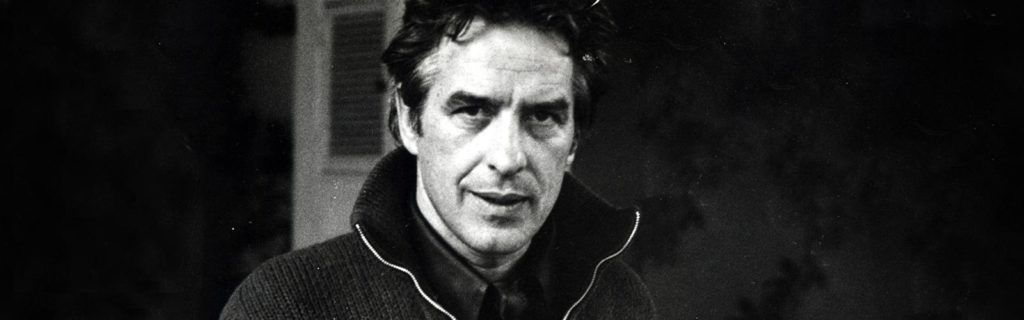

JOHN CASSAVETES: December 9, 1929 – February 3, 1989

When I was 20, the woman I was dating had jealousy issues. I had just started writing poetry, and wanted desperately to perform some of my poems on-stage at The Green Mill, which was – at that time – “ground zero” for Chicago performance poetry.. Despite being underage, I sneaked into the club one night and watched people perform, but was too frightened to perform any of my own work, which I harshly judged as inferior and unworthy of that stage. At the end of the show, my girlfriend and I went to the Mexican restaurant next door, where – despite my sullen demeanor – she accused me of being attracted to nearly every female in The Green Mill that night. She swore I was going to leave her, and she saw my desire to do anything but go to the movies and make out with her in her car as evidence of my desire to spread my wings and fly away. And so we sat, me silently eating burritos smothered in mole and infrequently pretending I didn’t remember the females she mentioned, as she accused me of crimes I had not even considered committing. More than anything, I remember being upset at her starting the fight in spite of my overt sadness at the immaturity of my writing. My unwillingness to defend myself finally wore on her, and she dropped her napkin on the table over her plate and said, “You obviously want to be with those women! Just go back there and be with them!”

There are good times to respond, and there are bad times to respond. My response was more of the latter. Because what I wanted to say was, “I don’t want to go next door and be with those women. I want to be with you. I feel comfortable with you. I belong with you.”

What I actually said was, “I don’t want to go next door and be with those women. They’re all too smart for me.”

Truth is a difficult state to attain. We all claim that we want nothing but truth, yet all of us mask truth in some ways. We view it through a personal perspective, we bias it, we ignore parts that are contrary to our needs. In reality, our searches for truth are more the creation of relative truths and rationalizations than anything. This is not so much a “human flaw” as “human nature”. And while many art forms try to represent this distinction, few do it well. One of the best, however, is cinema verite and one of its greatest directors, John Cassavetes.

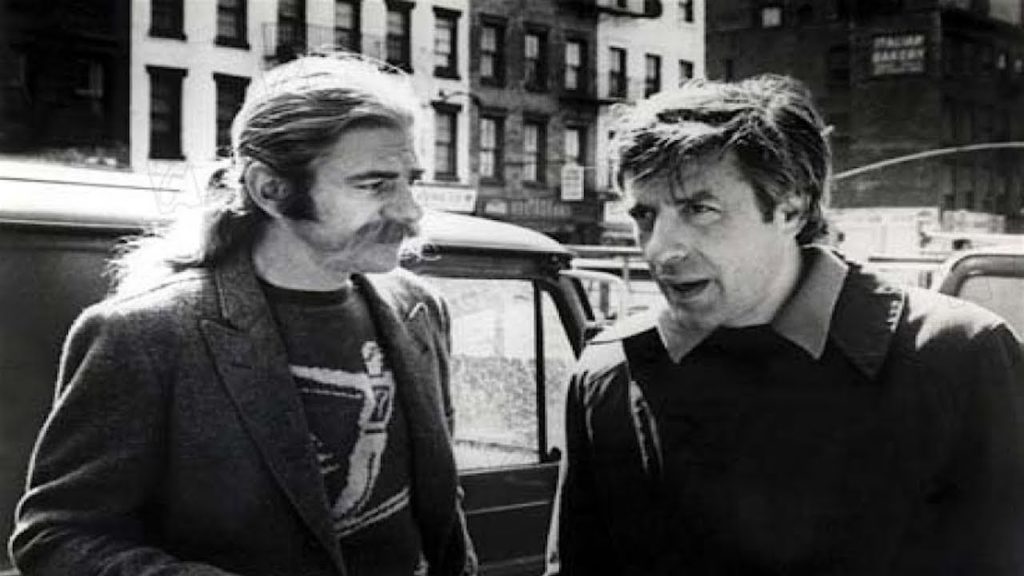

Cassavetes began his career as a television and film actor for major studios. Using the money from his acting jobs, he financed some of the earliest independent films, at times personally hand-delivering prints of the films from theater to theater. In his films, Cassavetes was searching for the kind of truth that typical films aren’t able to show. Studio films were (and remain) efforts to pose reality. The best films pose that reality in layers of relative truth, but drama is at its most widely-accessible when it works towards a definitive point of view – a relative truth for the viewers to grasp onto. Cassavetes wanted to capture something much more human. His films were about the very process of confusing and muddling the truth that we all do. In all of his independent cinema verite films, Cassavetes’ characters were all seeking the same peace that comes with identifying and accepting “the truth”. However, with each character chasing their own version of the truth, wrapped in its own package of perspective and ignorance and euphemism, the relationships between the characters (and their own internal resolve) always feels on the verge of collapse. Which is probably closer to real life than any studio film would be willing to portray.

His 1976 film The Killing of a Chinese Bookie was about a small-time strip club owner and minor crime figure Cosmo Vitelli (played brilliantly by Ben Gazzara) who loses so much money in a high-stakes poker game that he is forced to kill a Chinese bookie to stay alive. The film is reminiscent of the crime dramas of the period – notably Scorcese’s – but where those films mythologized criminals, Cassavetes’ camera is a fly on the wall. The lighting is bad, the settings are confined, and everything feels ugly and oppressive. And unlike Scorcese’s films, where the dialog is appreciated for its poetic representation of street life, Cassavetes’ actors improvise their lines, and they all speak like typical humans on an ill-defined quest for truth. New York Times film critic Vincent Canby described the dialog this way:

“Watching the film is like listening to someone use a lot of impressive words, the meanings of which are just wrong enough to keep you in a state of total confusion, but occasionally right enough to hold your attention. What is he trying to say? It takes a little while to realize that maybe the speaker not only doesn’t know but doesn’t even care to think things out. He hopes that if he continues to talk he may happen upon a truth as if it were a found object.”

And of course, that’s exactly what they’re all doing. Blindly searching for a truth they can live with. And that process is ugly and personal and rarely matches with the tropes of modern drama. In Cassavetes film, a broken character is not followed for a lengthy beat as sad music plays beneath them. Instead, the camera simply turns off. The scene ends, much the same way we avert our eyes when a stranger embarrasses himself in the mall.

Late in the film The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, Cosmo Vitelli tries to rally the performers at his strip club. His speech, as delivered, is “Mamet-speak”, with stops and starts and rambling confusion.

“Everything takes work. We’ll straighten it out. You know. You gotta work hard to be comfortable. Yeah, a lot of people kid themselves, you know. They, they know when they were born, they know where they’re going. They know whether they’re gonna go to heaven, whether they’re gonna go to hell. They think they know that. They kid themselves. Right? But the only people… who are, you know, happy… are the people who are comfortable. That’s right. Now, you take, uh, uh, Carol, right? A dingbat, right? A ding-a-ling. A dingo. That’s what people think she is,’cause that’s the truth they want to believe. But, uh, you put her in another situation, right? Put her in a situation that’s tough. Stress. Where she’s up against something,you’ll see she’s no fool. Right. Because what’s your truth is my falsehood. What’s my falsehood is your truth and vice versa. Well, look. Look at me, right? I’m only happy when I’m angry. When I’m sad. When I can play the fool. When I can be what people want me to be, rather than be myself.”

At the end of the speech, Vitelli admits the theme that runs through so much of Cassavetes’ work. He admit that he’s only happy when he’s being someone else. That life is easier when someone else has defined our truth, and we can stop seeking and just start acting. Because if truth is relative, anyway, it’s less difficult to give up and live someone else’s lie than to expend the effort of crafting your own.

In the real world, perhaps there are universal, immutable truths. Perhaps that’s the essence of faith. But for most of us, life is a process of seeking answers based in something solid, and we work tirelessly to give our arguments a solid foundation. And many of us seek and find, only to find our truth just as unfulfilling as the truths we avoided along the way. So when I spoke up that night in that Mexican restaurant, I said the wrong thing. What I wanted to say was, “I don’t want to go next door and be with those women. I want to be with you. I feel comfortable with you. I belong with you.” But what I meant was “I’m sad. And I’m hurting. And I don’t want them, but I’m not sure you deserve me, either.” A truth buried deep inside a prevarication inside a denial inside an insult. Somewhere, Cassavetes must have been smiling.