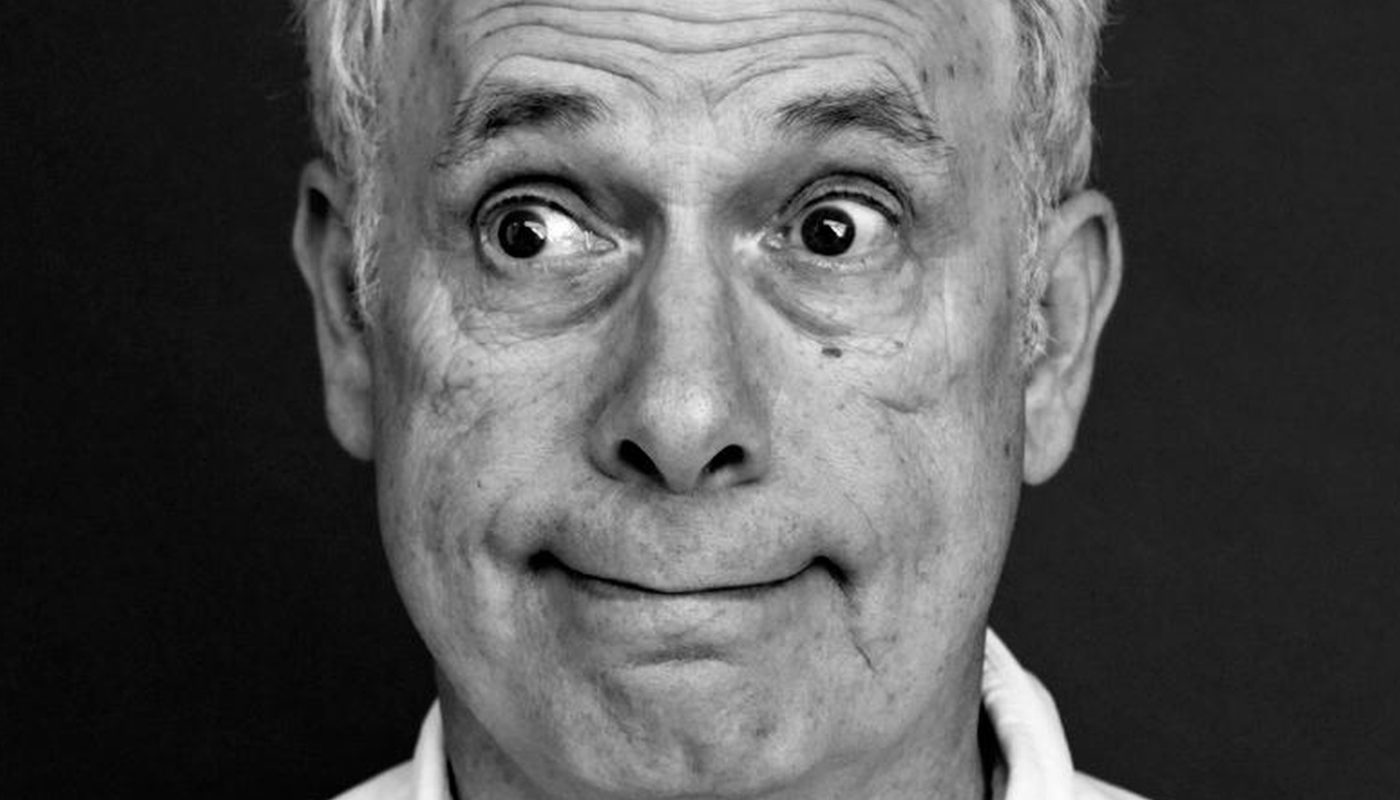

CHRISTOPHER GUEST: born February 5, 1948

It is my natural tendency to grow very quiet during arguments. I shut down and listen to what is being said to me (and about me) and give very little back. I have a similar tactic when I’m overloaded with anxiety. And when I’m sad. Also when I’m offended. And when I’m unsure of myself. Silence is my “go to” behavior, not as a defensive maneuver or as an attempt to be difficult. For years, I’ve genuinely questioned the value of the things I could say. My opinions never seemed important enough, my beliefs never grounded enough, and my thoughts never educated enough to merit inclusion in a conversation. The end result of that belief system left me feeling unbelievably isolated from everyone, which was the exact opposite of my intent. My original intent in remaining silent was to ensure that I didn’t inadvertently offend anyone or unknowingly come across as ignorant or stubborn. And yet, despite these good intentions, I eventually found myself largely ignored and irrelevant to almost everyone who mattered to me. This very project began as an attempt to remedy that, because I realized at the depths of that prolonged period that the only remedy to the distance created by silence was to speak. Unfiltered, unafraid… just speak. And I began to comb through my list of influences for those who might help understand the benefit of “just speaking”, and I quickly found one: improvisational genius and “mockumentary” filmmaker Christopher Guest.

I first discovered Christopher Guest through the National Lampoon Radio Hour. (I came to Spinal Tap very late in life. I had also known him from the synchronized swimming sketch on the 1984 season of SNL, but hadn’t realized that was Guest until a few years later.) The bit that stood out to me was “Flash Bazbo, Space Explorer”. In the bit, an announcer sets up an old-time radio serial about a lone space explorer, hurtling through the void. In each instance, the listeners find Flash Bazbo facing a perilous situation from the previous episode’s cliffhanger. And in each case, Flash Bazbo escapes by babbling the most idiotic things. It’s unsure whether or not Flash is retarded or unaware or in on the joke. All that is known is that Flash talks. A lot. In the first bit I discovered, Flash is facing certain death (pirates have him surrounded and are threatening to cut off his “you-know-what”, and Flash escapes by asking for a final request. His final request is a minute and a half of insane food requests, delivered in a rapid-fire ad lib. Flash stumbles and makes insane requests like “a candy cane… over easy”. It’s improv at its most ridiculous and I was hooked. Flash’s stumbles were real because Christopher Guest was stumbling. And as preposterous and silly as the moment was, it was also very real. I was hooked. I couldn’t get enough of Flash Bazbo, or Guest. I gathered as many of the National Lampoon Radio Hour albums and bits as I could find, and combed through them for Christopher Guest bits. Guest was doing something raw and – despite its outrageous premise – something very real, and I loved it.

When Guest directed Waiting For Guffman in 1996, it quickly shot to the top of my list of favorite comedies. I’m not sure how many times I’ve watched it, but I’m fairly certain I can recite any scene verbatim. The film followed the same playbook as Spinal Tap, with Guest (and writing partner Eugene Levy) creating characters and their backstories, and laying out a framework for the movie. The “script”, such as it was, was nothing more than a series of scene description: “Corky asks the city council for more money”, “Libby discusses going to New York”, “the couples have dinner”. Guest follows the “mockumentary” style of comedy, and the film is liberally peppered with “talking head” interviews where characters answer unheard questions to an off-screen interviewer. In an episode of The Kevin Pollack Chat Show, Guest admitted that there was no off-screen interviewer, nor was there a prompting question. In fact, the scenes weren’t even scripted to address a specific question. Guest simply set the scene up, called “Action!” and allowed the actor to start talking. It was that simple. Guest realized that the more time the actor had to talk, the more human the character would become. In one scene, Libby Mae Brown (played by Parker Posey), the dimwit ingénue of the small community play, describes her daytime work at Dairy Queen. “I’ve been working there for seven months… eight…?” And then Libby falls into an almost trancelike state, her mind desperately trying to decipher the number of months she’s been a Dairy Queen employee. We never see her resolve the problem, but we get to watch her hang in there for a ridiculous amount of time. It’s a remarkably human moment that we would never see in a scripted film, but it’s one we’ve seen in real life. And what we witness is not just Libby Mae Brown struggling with counting, we’re also witnessing Parker Posey struggling with a backstory.

Guest – in his personal performances and in the films he creates – understands that the key to a great performance is to just keep talking. While scripted films rely on cinematography, editing, set design, lighting, and sound to create evocative moods (and can therefore leverage a character’s silence to help drive understanding of the character), improv movies are all about the performance. They require the actors to give something of themselves. Our depth of understanding is limited only by how much the actor brings forward, primarily in what they say. We connect with the character from what we’re told. Without those words, we’re left to fill in the gaps with our own imagination, and we create the (often less-funny, as we aren’t professional comedians) narrative within the confines of our own thinking.

In my life, I’ve been described as “an open book” and “impossible to read”. I used to wonder if I was duplicitous or phony, but the reality is, I’m mostly just silent. I joke, I toss in comments here and there, but I don’t willingly or effortlessly share much of what’s inside my head. So if you’re looking to connect with me or understand me, you’re likely to find me closed off and distant. However, if you’re just looking for someone to make you smile without having to worry about what they’re thinking, I’m your “go to” guy. Not surprisingly, the relationships that mean the most to me are in the former category; the latter is mostly fun-but-temporary friendships. What Christopher Guest understands – and improv highlights – is that we have to keep communicating in order to understand each other. That if we wait in silence to craft the perfect phrase or the flawless response, we often times miss the opportunity to give something of ourselves. If we do it often enough, we end up isolated and misunderstood and resented. To Guest, the perfection of what we say is irrelevant. Just speak. And keep speaking. The world will have no choice but to get to know you.