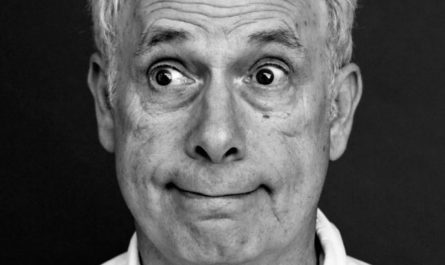

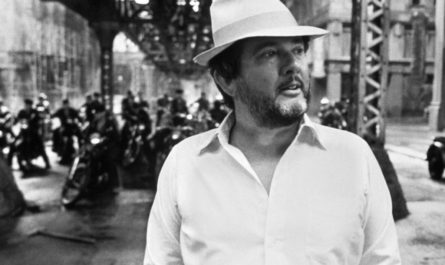

SPIKE LEE’S SCHOOL DAZE: Opened February 15, 1988

The news today carried the story about lawmakers pressing the owners of the Washington Redskins football team to change the team name. The reaction from certain segments of America was, not surprisingly, hostile and frustrated. Facebook posts and blog posts and radio interviews and email lists were choked with critics of “political correctness run amok”. Most of them cited Native American friends who were “not the least bit interested” in this issue, and who didn’t find the team name offensive. Most of them cited “real issues” that needed to be dealt with. (Not surprisingly, the “real issues” were generally worded with a seriously racist word-code like “inner city youths” and “welfare queens” and “Muslim terrorists”. Most egregiously, the talking points all seemed to have a plan for “what Native Americans really need”, which was usually alcohol treatment. All of the commentary pre-supposed a deep knowledge of Native Americans and their behaviors and beliefs and biases. The real problem with ignorance is that it’s always covered by such a healthy layer of certainty. The problem with arguments like these are that they presume racism is an action, not a system. That racism can simply be avoided with a careful set of behaviors and beliefs. But the systems we live in were built on an unequal foundation, one that was racist and sexist and classist. And while our actions may not be overtly racist, we still owe a certain willingness to be aware of the system in which we live. Part of that awareness is to see beyond the narrative we’ve been shown. To recognize that our perception of say, Native Americans is likely incomplete if it is only through mainstream media, school text books, and a friend or two with Native American ancestry. If we’re basing our truth and our opinions on the narratives we’ve seen, it would only be fair and objective to see as many of those as possible. And yet, we rarely do. We may see many images of black culture, but repeating the same image with different actors over and over is not a complete picture; it’s propaganda. And this was the state of black representation in film when Columbia Pictures gave celebrated student- and independent filmmaker Spike Lee about 6 million dollars to make his first studio film, School Daze.

The film medium is similar to so many other elements of society. For years, films were made that were not overtly, directly racist, chock with horrific stereotypes and blatant “hate speech”-type language. Most did not have a spoken anti-minority slant; they simply lacked any evidence of minorities at all. If minorities were cast, it was generally in roles that fit specific stereotypes, and rarely carried the plot forward at all. An elevator operator. A shoeshine boy. This wasn’t racist by intention, so much as racist by omission. It was racist because, as they made the film, the filmmakers never even considered minorities at all. And so when black cinema took off in the 1970s, it was as reactive as it was exciting. Seeing black actors in all the roles in a film was exciting and important, but many of the films had a similar theme of kicking against white society. Undoubtedly, this was an important – and brand new – theme, and few “blaxploitation” films of the ’70s exist outside of this fight against the systemic oppressions of typical white society. It is fights against racist cops and racist courts. It is the fight against unfair schools and systemic poverty. The films fought against redlining and gentrification and poor education. And throughout the film, white characters stood as avatars for the institutions they represented – in the same way they do in real life. School Daze really doesn’t seem to care about those avatars. In fact, there are no white people in the movie at all. “Whiteness” in this movie is strictly an overriding construct that exists from the first shot, which shows a drawing of a slave ship with hundreds of slaves laid out like cordwood in an orderly fashion to maximize the profitability of the Middle Passage journeys. Not a single white man in the picture, but the “whiteness” of is apparent. And by contrast, so is the blackness of it. School Daze was setting the stage to tell the story of people continually affected by whiteness, but no white people are needed to tell that story. Given a few million dollars and a major studio thumbs-up, 30-year old Spike Lee made a movie of, by, and for an audience that had been deprived of their story up until that point.

When I first saw School Daze, I loved it first and foremost as a film-lover’s film. Spike Lee clearly loved film, and made references to numerous genres throughout the film. It was a drama, then a comedy, then a musical, then back again. It was a love letter to film genres, set in a black college in the South. It was only late in the film that I recognized that it was the first film I could think of set in a black college. And not for any narrative purpose. It was not a film about black students’ efforts to struggle against white oppression. Mission College was simply a black university with black students, each as varied and unique as any other university. And while white society outside of Mission College after graduation would likely provide each of these students with unfair disadvantages and prejudices, inside they were just students. There were lazy students and funny students and political students and fraternity/sorority students. Nothing about the film indicated that the characters were in a constant struggle to reconcile their value within a white power structure. It was an eye-opening theme, given that nearly every black character in film I’d experienced up to that point had been pre-occupied with that struggle – or had surrendered to it, completely.

Beyond that, Spike Lee provided an open view into matters not only unseen by film audiences, but unknown to most of them, as well. It was the first time I was made aware of colorism and the inner disagreements about natural versus processed hair, a topic so pronounced he turned it into a Stanley Donen-inspired musical number, “Good and Bad Hair”. I’ve since had friends tell me that School Daze wasn’t greeted as warmly as many of Spike’s other films because it pulled back the blanket on some of the issues of black culture that people would rather not have exposed: the pettiness, the infighting, the internal struggles for acceptance among others of the same race. But by doing so, Spike made one of the most honest films about race in the history of American cinema. Because few things can empower as much as having a voice. Few things minimize our existence as greatly as not feeling heard, or feeling like we have the power to voice our thoughts. Spike Lee provided the first film that gave that voice without any conditions. School Daze is filled with the voices of people being people, not just people in contrast to a system. If School Daze will go down in history, it will go down for just how loudly it spoke without having to preach.