The Big Lebowski: Premiered March 6, 1998

A primatology study published in 2009 proved that all of the great apes – gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, orangutans – all laugh. It sounds simple enough, since apes share so much DNA with humans. But prior to the study, it was unsure if they actually laughed, and so a team of researchers took to tickling great apes, and checking their response. Sure enough, apes laugh when tickled. Some apes laugh on both the inhalation and the exhalation (think Horshack in Welcome Back, Kotter) while others laugh only on exhalation, like typical humans. Once the researchers determined that the breathing pattern and throat contractions were the same between humans and great apes, they began to question why. What evolutionary advantages do we achieve by laughing? Many researchers came to the same conclusion. Before we had words to soothe each other, we had laughter to tell each other that things were okay, and that we were safe as a group. Even now, when we’ve developed words, we trust them less than laughter. Here’s a simple test. Ask two teenage girls a difficult question, and watch their response. Inevitably, they will start to laugh. Not because anything is funny, but to assuage each other and remind each other that – despite the tension – all is well. People will laugh before they will tell each other that things are safe, and the results are the same, if not better. It’s also the reason women regularly list “sense of humor” as the most important quality in a man; they’re not looking for a comedian, they’re looking for a man to feel safe around. Which is why art that makes us laugh is so important, particularly art designed to bring people together. One of my all-time favorite pieces of art created for this purpose was the Coen Brothers’ The Big Lebowski.

The interesting thing about The Big Lebowski is how I came to love it. 1996’s Fargo had been – and remains – one of the greatest films I’d ever seen. I’d been a big fan of the Coen Brothers’ earlier films – Blood Simple, Raising Arizona, Miller’s Crossing, Barton Fink, even The Hudsucker Proxy – and so I was primed for their newest film. Plus, I was a fan of most of the movie’s stars. I had recently moved from Chicago (where I had grown up) to a small military town in coastal Carolina. I was excited that this would take my mind off the culture shock I was experiencing, and hopefully make me miss Chicago a little less. I caught a daytime matinee soon after the film opened.

And I hated it.

Not just “disliked” it. I hated it. When I tried to explain the plot to my girlfriend, it made no sense. I gave up quickly. It was simply a horrible mess. A movie that went nowhere, for no real reason. In the end, the plot devices that drove the movie turned out to be faked… I simply couldn’t make sense of any of it. Worst of all, it simply wasn’t funny. It was very strange, but not really funny. I had smirked a few times, and I had arched my eyebrow a few times, but I don’t think I ever laughed at the film. It was simply a trainwreck, and I was disappointed that two filmmakers I really loved seemed to have run out of steam at the time when I really could have used a laugh. For the rest of that year, when people told me they liked the film, I assumed they were idiots. It wasn’t until I made a trip back to Chicago and spent some time with my uncle and cousins, all of whom share a similar sense of humor with me. They mentioned how much they loved the movie, and I was baffled and let them know. Their response was similar. They could not believe I didn’t love the movie. They talked about sitting and watching it together, and as they talked about it, they began to laugh. It was wintertime, and we were shoveling a driveway, and as we shoveled, they started saying lines from the movie and laughing hysterically. Without realizing it, my mind started to shift. They’d say a line, and I would find myself thinking, “Okay, yeah, that’s a funny line.” In very little time, I was laughing along with them, wondering why the line hadn’t seemed funny at the time I saw the movie.

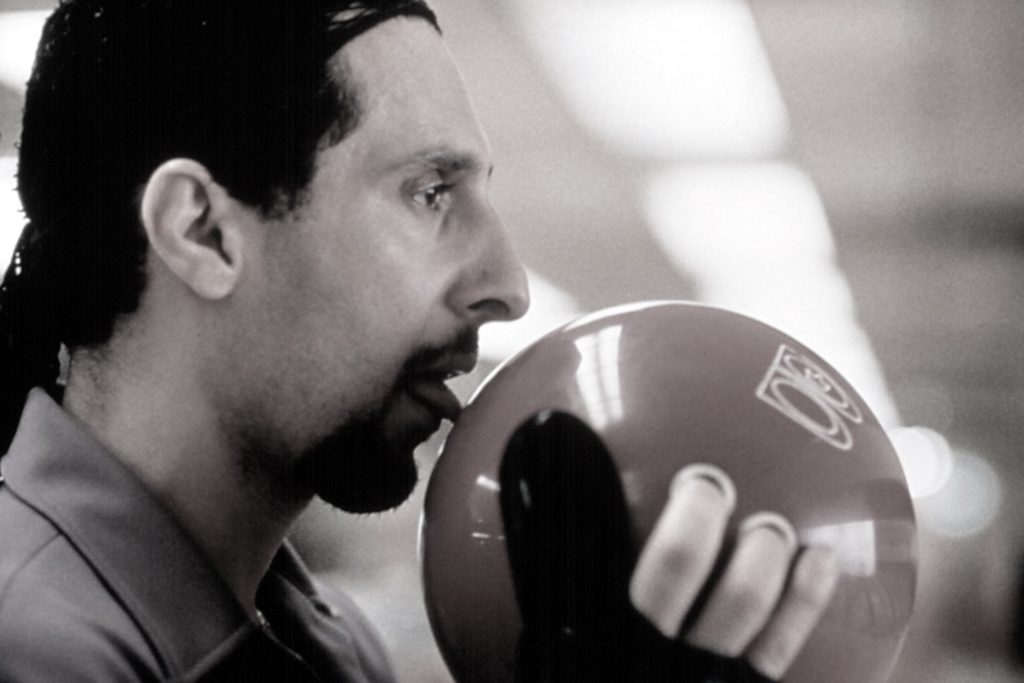

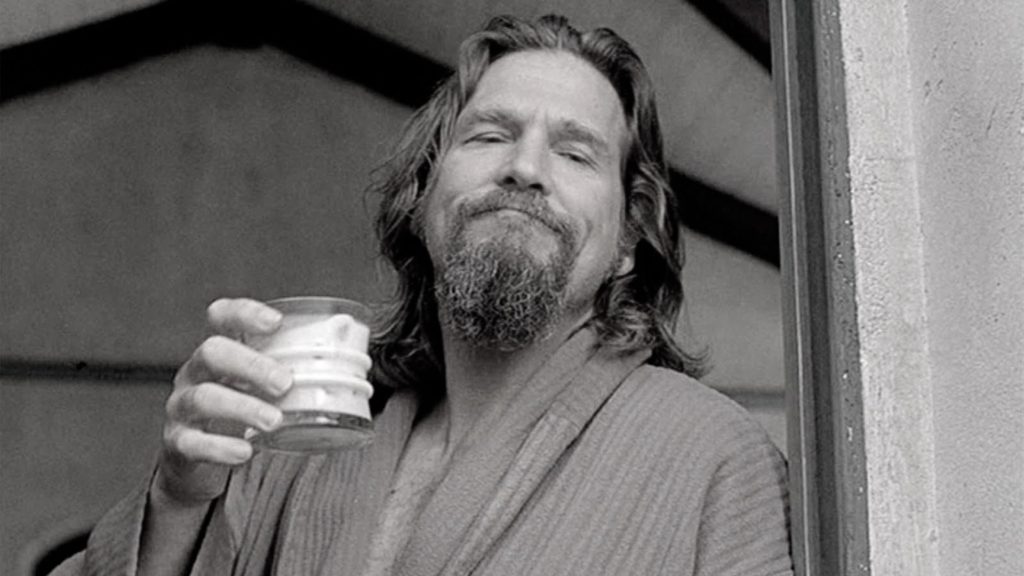

When I got back home to Ohio, I rented the movie and watched it again. It was hilarious. I began to talk about it with friends and co-workers, all of whom loved it. We could sit for hours and share lines from the movie and crack each other up. And there the movie stayed, as part of the collective sensibility between me and my good friends, a sort of comedic touchstone between us. I don’t think I’ve ever seen the movie with any of my close friends, and yet I bet a month has not passed in over a decade where we haven’t said at least one line from the movie to make each other laugh. That’s the magic of The Big Lebowski. If you try to break the script down into something intelligible, it only barely makes sense. From the “plot” perspective, it’s a nightmare. It’s a case of mistake identity on top of a fake kidnapping, a coerced insemination storyline, mixed with angry nihilist porn stars, a television writer in an iron lung, and a pederast bowler in a hairnet. Narrated by a cowboy who spends his time in a bowling alley bar. And Donnie, who never learns to shut the fuck up. But the film is more than that. The film is a series of absurd performances and funny lines in ridiculous scenarios. It’s a film that screams for a group viewing, where we sit with our friends and – like the teenage girls faced with a confusing question – we laugh. We laugh at the crazed Viet Nam vet attacking the Trans Am with a golf club, not because it’s inherently funny, but because it’s so absurd and the character is so invested in the moment. More importantly, the dialog throughout the movie is extremely quotable. And I believe it was written that way for a reason.

Fargo was a brilliant film. It was funny, but Fargo was about introspection. It was about the mistakes we make and the mistakes we refuse to face up to. It was a movie that asked us to consider why people do the horrible things they do to each other. It was a film about dark secrets and delusion, and our capacity ot indulge both. The Big Lebowski addressed a number of those issues, but it flipped the scenario. Fargo demanded we consider these ideas; The Big Lebowski told us not to worry about it. Most of the issues resolved themselves, anyway. The Big Lebowski reminded us that the world can be a terrible place, but if we surround ourselves with friends, we can face those issues the way teenage girls handle a difficult question. We can laugh. We can remind each other – in a way designed before language – that it will all be okay. And we can laugh. But we have to do it together.