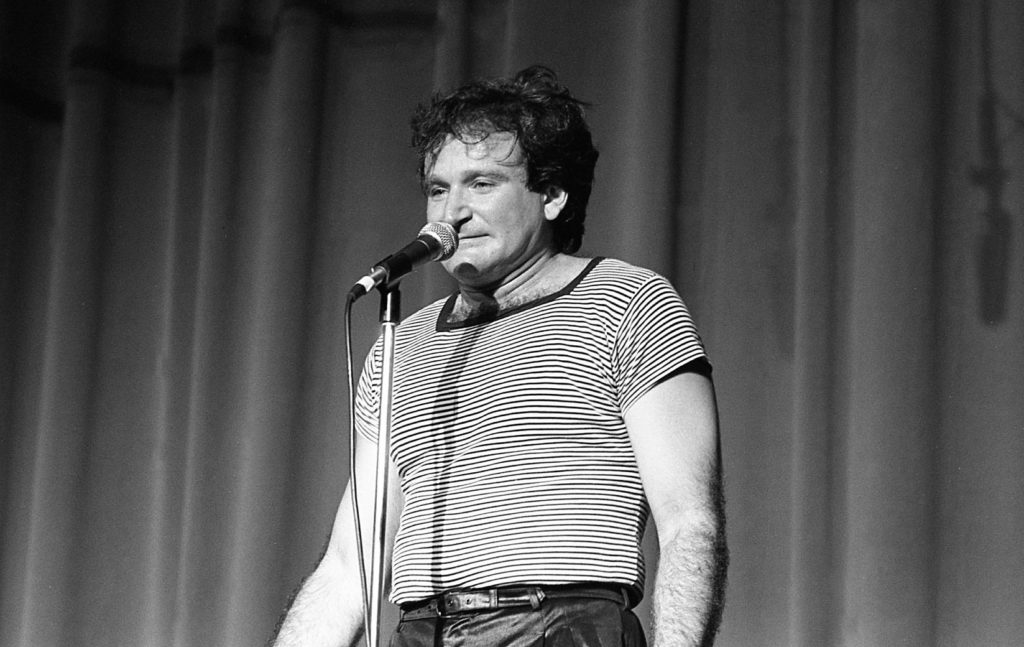

ROBIN WILLIAMS: July 21, 1951 – August 11, 2014

I was just thinking about Robin Williams a few days ago. We were driving out of town to visit family and I was listening to some podcasts and he was mentioned in two different podcasts. In both instances, he was discussed as a lover and a supporter of comedy, and the comments about him were glowing. I have a lot of comedy heroes, and for me to pretend that Robin Williams was one of them would be a lie. But listening to the positive comments about what a difference he made in the lives of these comedians, I felt a warmth for him that was beyond the warmth one feels for an artist because we’re so in love with their art. It was the kind of warmth you feel as you grow older and realize that sometimes you don’t have to set the world on fire; sometimes you just have to be nice and appreciative and supportive and that creates an environment where many other people can set the world on fire. As a young man, I was only interested in the former. As I grow older, I am beginning to see the value in the latter. And it was within that reflection that I found a certain fondness for Robin Williams.

And again, I never disliked Robin Williams. I was just never much of a fan. I was raised on Mork & Mindy and like most of America, I loved it. Williams’ first improv special with Jonathan Winters was my first introduction to improvisation, and I still recall clearly the diner sketch where he and Winters tried to out-mispronounce the word “coffee” in an effort to break the other one up. But I never cared for Dead Poet’s Society, and I never saw the kids movies he did (Hook, Jumanji, Mrs. Doubtfire…), and if I’m being perfectly honest, his stand-up was always a little too frenetic and theatrical for me. But there’s plenty about him that I liked and admired (One Hour Photo, Insomnia, World’s Greatest Dad). And one fact that had always stuck with me was that he was one of the last people to see John Belushi alive. I remember reading about their friendship in 1984 in Bob Woodward’s flawed biography of Belushi, and how Belushi’s unexpected death caused Robin Williams to change his life, dramatically.

By the late 80s, I was in high school and Williams was an open and honest advocate for a sober lifestyle. And despite his lack of cocaine, his performances and interviews were as wildly-disjointed as ever. Williams’s rapid-fire ability to leave one narrative and chase an idea down a rabbit hole – immediately, passionately, and with specificity – spoke to something in his head. Interviewers always tried to describe it as “manic”, but his was the voice of conflict. The voice of a man whose primary thoughts were always competing for attention with his supporting thoughts. A man who seemed to battle with conflicting thoughts and alternate theories and connecting ideas, each demanding equal attention, and to which – on stage, at least – he would regularly yield. We all have small voices in the back of our brain that challenge the narrative we’re presenting to the world; Robin Williams’ comedic gift (and possibly his curse) was the ability to yield to those voices.

So it shouldn’t have come to a shock when he eventually fell off the wagon after 20 years of sobriety. But it did. It shouldn’t have come as a surprise when he disclosed his longtime battles with depression. But it did. Given his stage presence, it shouldn’t have been a surprise to learn of his bipolar disorder diagnosis, but it was. Further relapses followed. And throughout it, we remained confounded or uninterested or disbelieving that he was a man with problems. He could make us laugh, he could make us cry, and it seemed like every story that came out about the man was the story of a genuinely caring, considerate, supportive individual. (Click this link to read one of my favorites, courtesy of the amazing Dana Gould.) And if social media is an indicator, people everywhere have been struggling to make sense of that contradiction. The contrast is too stark, and there seems to be a collective sense of complicity – people feeling guilty for receiving so much from Robin Williams while being unaware of the scale of pain he was experiencing. Commentary seems to run one of two directions: either a focus on all the laughter at the expense of the sadness, or calls for understanding and support of depression. Both are fine, noble ideas, but neither really resolve the complexities around our relationships with someone as complex as Robin Williams. Because we want to think of him as one person, but his public persona should have been the warning sign. He was a man filled with conflicting voices and nagging narratives, so much that they overfilled into his speech and his behavior. Which is fine if those voices are healthy and inquisitive, less so when they’re the voices of inner demons trying to destroy you.

When Philip Seymour Hoffman died, I wrote about how some people’s demons lie in wait for them. My thinking that day was that our personal demons could be exorcised, and that failure to truly defeat them was like living in a constant state of willpower. We fight them for as long as we can, while they patiently bide their time until we’re vulnerable, and then grab us again. But that was a meditation on addiction, and despite using the plural “demons”, I was really talking about a single demon. Robin Williams’s life is a more accurate representation of real life. You fight the demon of depression until it subsides, and then you fight the demon of addiction, and then you fight the demon of bipolar disorder… And so on. You fight them with comedy and kindness and support and all of the things that make people love you. Perhaps you use these tools because they make people love you, which aids in the fight. But the terrifying moment I had when I’d heard that Robin Williams had killed himself was the understanding that sometimes, some people just don’t have any fight left in them.

Because I’d like to believe that we can not only win the battles with our demons, but that we can win the war, as well. That we can vanquish them from our souls and become new people, altogether. But the truth is, I have my doubts. As someone who has spent his life battling with his demons on a daily basis, I’ve felt the emotional collapse from beating back one personal demon, only to have another pop up. I’ve often described life as a series of tamping down personal demons, an act similar to trying to submerge dozens of tennis balls floating in a bathtub. You grab as many as you can, and you seek inventive ways to hold them, but you only have two hands and some will always rise to the surface. Sometimes, you’ll try to submerge too many, and a bunch of them will fumble from your hands and reach the surface. It’s a war of equal parts strategy, faith, and desperation. But the belief that I could stop trying? That’s foreign to me. And so as I was sitting at a cookout and checked my phone and saw the news alert that Robin Williams had killed himself, I immediately thought of that Sisyphean task and grew resentful. And then fearful. Because while I have accepted that I may never be able to stop, I actively deny the fear that the task may some day break me. And I can’t figure out which is worse: that Robin Williams had to die to make that fear more apparent, or that he could have lived his life in battle and I never would have really felt it.

If nothing else, we can take comfort in the fact that Robin Williams has finally stopped having to fight that war. He’s left behind a legendary comedy legacy that will outlive us all. I only wish he could have figured out a way to stop the battles before they started. To have left the demons far enough behind as to never need to engage them again. Not because that would mean I could watch more of his movies, or see more of his comedy specials. I was never much of a fan, anyway. But because it could give me hope that a change like that was even possible. He’ll be missed, but missed as the rest of us battle our demons. Over and over and over again. In the uncertain belief that it may never stop.