Bruce Springsteen’s Darkness On The Edge Of Town: Began recording June 2, 1978

We shall not cease from exploration, and the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time.

– T.S. Eliot

When the superintendents of Venice, Italy were charged with commemorating the Italian victory over Ottoman marauders in the late sixteenth century, they decided to build the perfect citadel in the northeast corner of the country. The city, named Palmanova, was a perfect nine-pointed star surrounded by a moat. At the end of every point of the star was a rampart where soldiers stood guard. Within the city’s walls, the streets were laid out in the purest, most elegant geometry. Angles were perfect and sharp, and the building facades were all kept clean and uncluttered. Foliage was added to enhance any view, without being distracting. The entire city had no jarring angles or inconsistencies in design or layout. Its design was laid out with mathematical precision. It would take neuroscientists centuries to prove what the designers of Palmanova knew from the humanist philosophies: expansive, uncluttered views would bring a sense of peace and harmony to the human mind. Inside this walled fortress, merchants and artisans could live peacefully, despite the city location in the direct path of Ottoman raiders coming out of Turkey and Bosnia. The settlement’s founders envisioned a world where citizens could calmly live their lives while the world threatened murder around them.

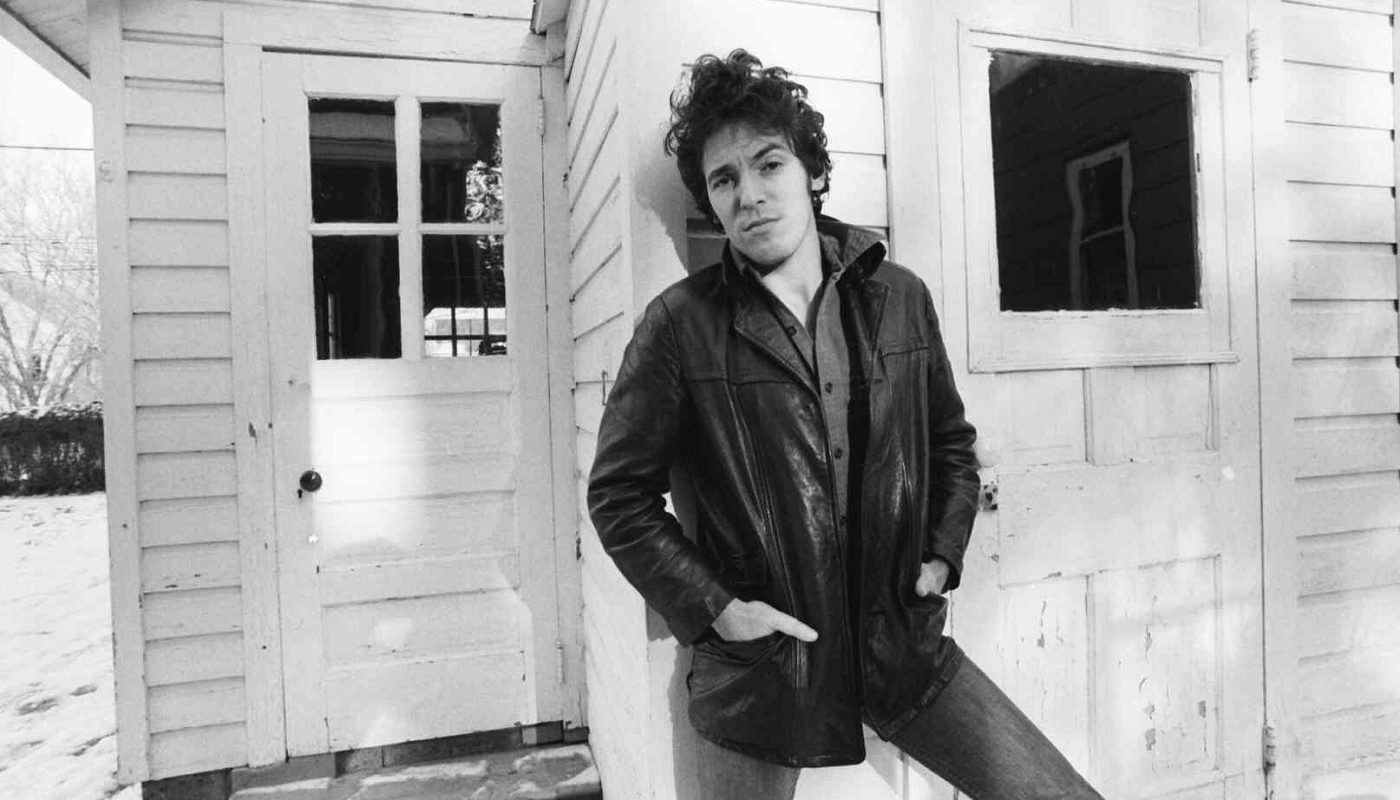

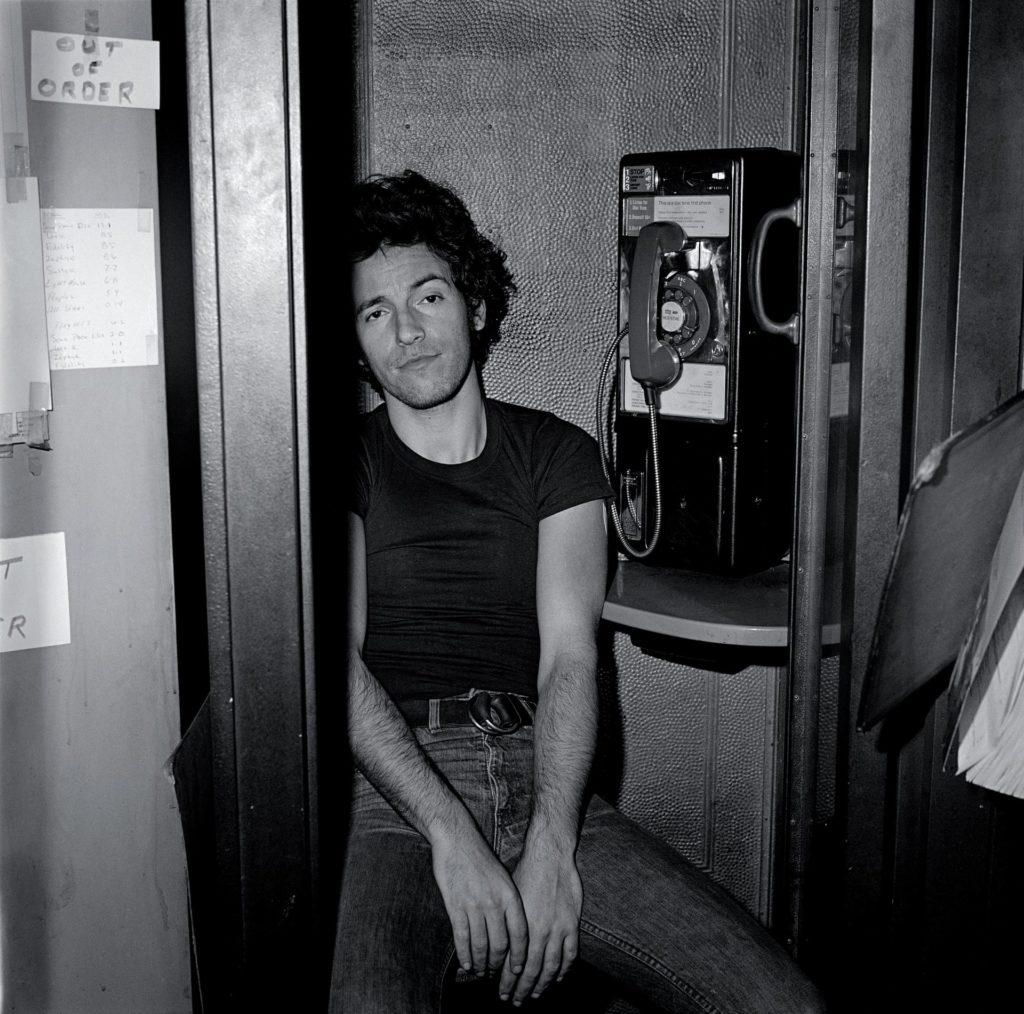

When Bruce Springsteen released Darkness On The Edge Of Town in 1978, it was after a brutal two-year legal battle with former manager Mike Appel over the rights and direction of his own career. The album was his third studio album, and followed up the huge success of Born To Run. Born To Run had not only made a huge impact on the rock charts, it also provided two songs which would become album-oriented rock staples. Audiences and critics assumed the long-awaited follow-up would be more of the same. Had Mike Appel beaten Springsteen in court, it likely would have. But Springsteen had different ideas. Instead of chasing chart positions, money, or fame, Springsteen claimed he was seeking “greatness”. And Darkness On The Edge Of Town was evidence of the greatness Springsteen would eventually achieve. Whereas Born To Run was an album about escapism, Darkness On The Edge Of Town was a testament to the power of home. The stories in Born To Run were loaded with tales of young love hampered by a stifling society. It was riddled with dead-end roads and frustration and creative depletion and degradation of youth. The songs were all dreams of a better world that must exist somewhere, despite any evidence to the contrary.

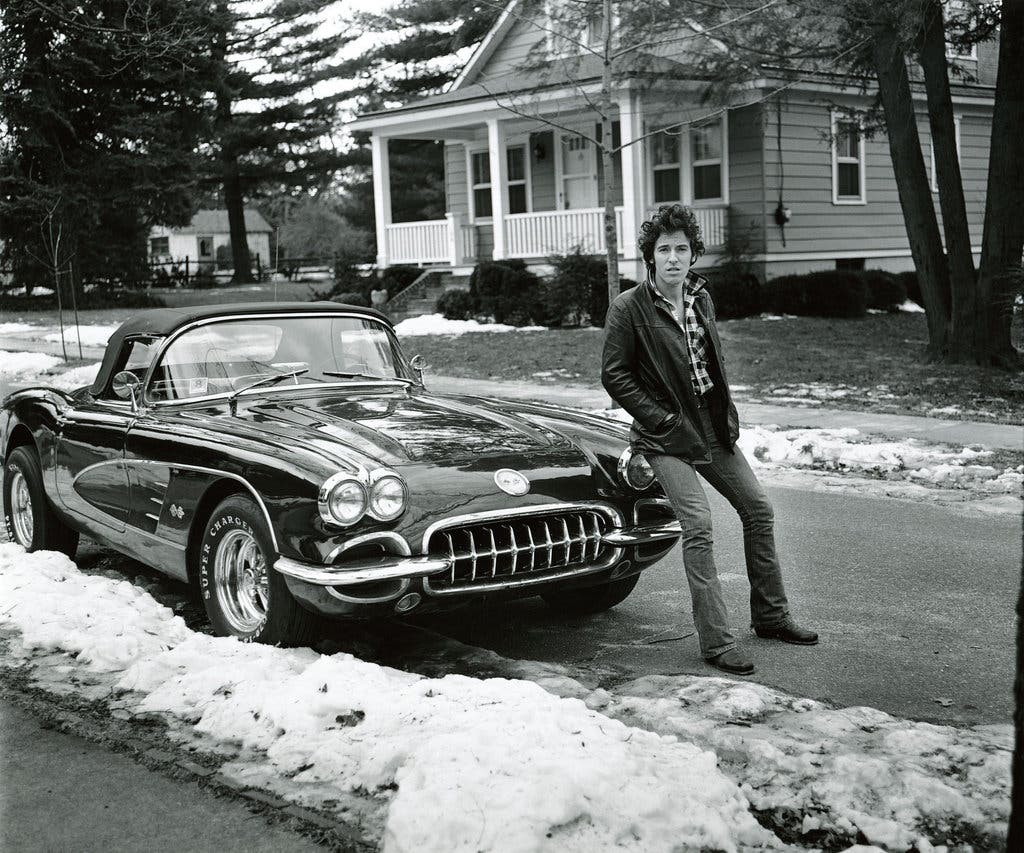

Darkness On The Edge Of Town on the other hand, was an homage to the safety and security of a hometown. The characters in the songs were not searching for a distant “better”; they were learning to be content with what they had. They found comfort in seemingly meager successes: winning a small-town street race, reflecting on the better days of a facing love, Even when their dreams have crashed around them and the characters on the album recognize that they’ll never achieve the dreams of their youth, they still have moments of grace. In “Racing In The Street”, the narrator describes a youth as the greatest street racer in his small New Jersey town. He provides more detail about his car than about the love of his life. And now that they are older and all of their dreams have faded away, he recognizes that in their deepest moments of bitterness, they can find salvation – in the car that brought them together. “My baby and me, we gonna ride to the sea / and wash these sins from out hands”. Springsteen had turned with this album; greatness was no longer “somewhere out there”. Now he seemed to realize that greatness – as well as meaning, and purpose, and potential- was a product of our lives, and leaving our lives behind was not only missing the point, it was dangerous. Because it was within our own worlds where we could find salvation; the darkness outside of town held only danger.

Like the city of Palmanova, Darkness On The Edge Of Town advocated hometowns as a haven from the dangers of the outside world. Born To Run had pushed Springsteen out of his niche as an unknown Asbury Park songwriting genius and thrust him directly into the kinds of “greatness” that album’s characters were seeking. Two years and countless legal hours later, his songs returned to Asbury Park with a scarred knowledge of the brutality outside of his small world. Encouraging people to appreciate what they had (no matter how meager) was a bold creative decision for a country headed into a period of hedonism and disco-fueled excess. Because it’s not a message we’re inclined to accept. Our lives are peppered with hurdles and roadblocks between us and our goals, and that’s for those lucky enough to even have goals. Circumstances mount to keep us from chasing our dreams, until our daily lives become the blinders that keep us from even seeing our dreams. And eventually, what we have begins to feel like the barrier keeping us from what we want. And so we hate our home. We tire of our job. We resent our spouse. And we long for anywhere else. Anything else. Anyone else. It’s a scenario most people have experienced, and there’s nothing more disturbing than facing the fact that the (literal and metaphorical) hometown you’ve committed to yourself to is no longer sufficient, and the desire to run away becomes difficult to deny. We want to move. We want to change locations, or careers, or spouses. We want to leave all familiarity behind because we’re certain the hopes and goals and dreams to which we might aspire are “out there”, somewhere. We’re not exactly sure where, but just… somewhere.

When building the Palmanova settlement, designers recognized that people might eventually feel cloistered and resentful of their situation, so the designers built the city to evoke only the most peaceful sensations. Springsteen acknowledged something similar. In his songs, the narrators all needed to stop looking to the darkness outside of town for their salvation, and instead find it within. In some cases, it’s within their own souls, in other cases it’s within their hometowns. But in each case, characters find it by looking within. And salvation is a huge theme on the album. Darkness On The Edge Of Town doesn’t measure success on any quantitative scale; it’s an album about saving ourselves. If the songs on Darkness On The Edge Of Town show anything, it’s the power of not destroying the people, places, and philosophies we’ve adopted. Because feeling trapped and resentful is understandable. But burning our world to the ground and running off into the darkness is escape, not salvation. Salvation, Springsteen posits, is a process of reconciliation, and it can only be found where you are. It can only be discovered with the people and the places and the things we love. Or once loved. And maybe we could leave and get lucky in the darkness, but the odds are unlikely. We owe ourselves more than escape; we deserve to be saved, and the only place we’ll truly wash the sins from our hands are the places we’ve already been a million times. We just need to see them anew by dusting off the surfaces we’ve neglected, by tending the wounds we’ve opened, and by crafting a vision for the future within the place we have always known as home.