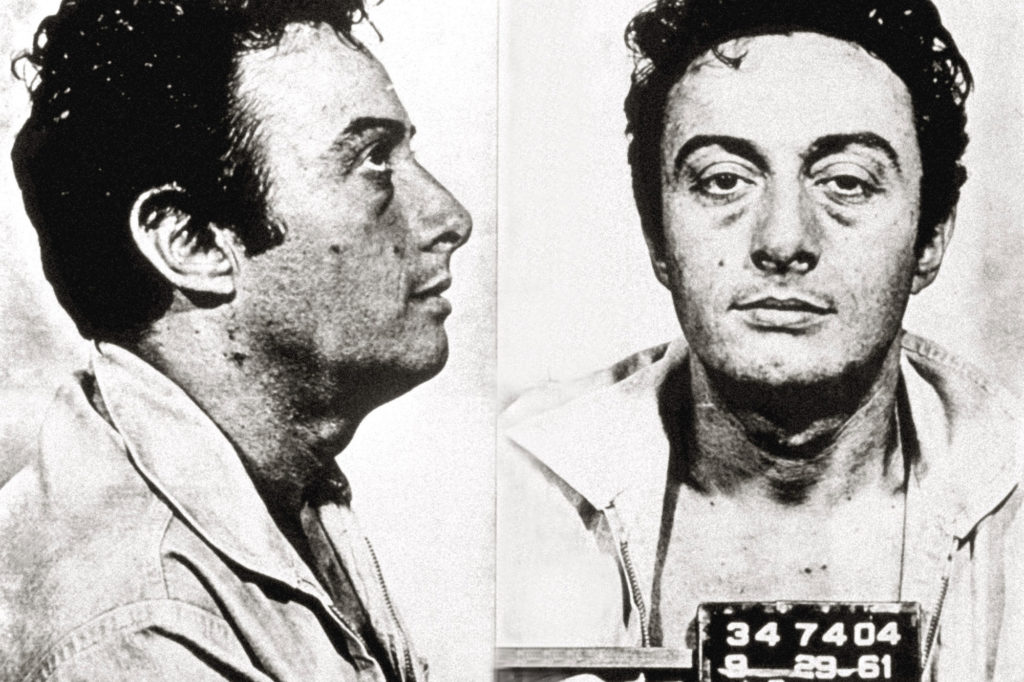

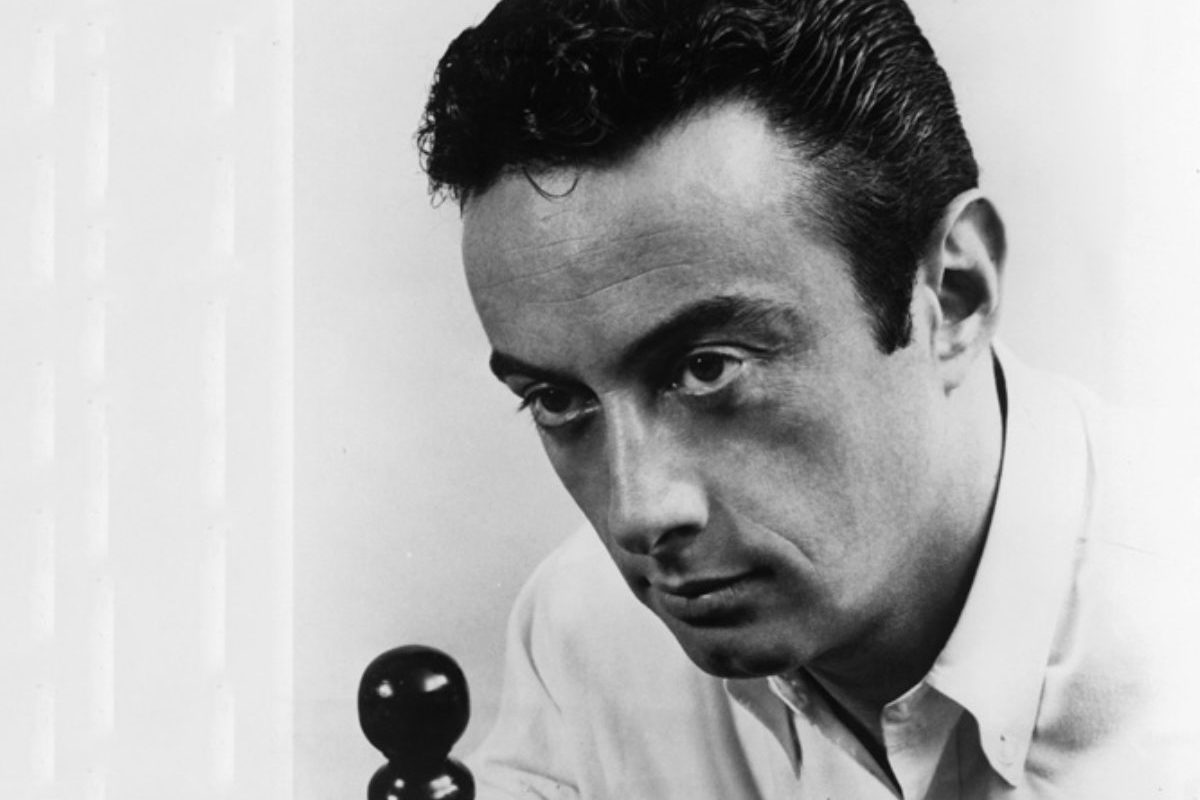

LENNY BRUCE: Arrested at the Gate of Horn, Chicago, December 5, 1962

Watch your thoughts; they become words.

Watch your words; they become actions.

Watch your actions; they become habit.

Watch your habits; they become character.

Watch your character; it becomes your destiny.

– Lao Tzu

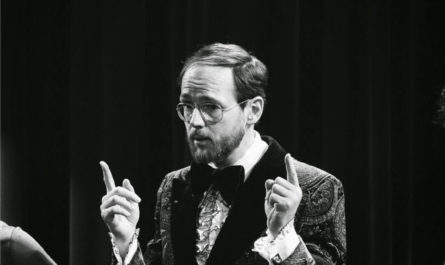

On December 5, 1962, Lenny Bruce was arrested on obscenity charges at Chicago’s legendary Gate of Horn nightclub, in the basement of the Rice Hotel. In the middle of the performance, an undercover officer in the 100-seta crowd had left the club to call for backup officers due to Bruce’s obscene material – specifically, use of the word “cocksucker” and jokes about the Pope. Eight police cars rolled in front of the exits of the club, arrested Bruce while he performed, and kept the crowd to check and register their IDs. A few nervous patrons were worried about being arrested for being a part of the audience. Others were offended by the accusation of obscenity and the commutative accusation, and became verbal enough to get themselves arrested, as well. (Among those arrested was a 25-year old New York comic who would later have court issues of his own – George Carlin.)

Lenny’s Chicago arrest and trial were disturbing over-reactions to a previous year of court battles for obscenity. Lenny had been arrested in San Francisco in late 1961 on similar obscenity charges, but was later acquitted. Other areas of the country, however, were put on alert. Unlike the east and west coast, midwest areas were determined to make sure Lenny didn’t spread his obscenity in their city. The defense of the San Francisco arrest was a defense of rhetoric. In fact, the arrest had been a bit where Lenny deconstructs the etymological and rhetorical meaning of the phrase “to come”, parsing it out like a English professor and discussing how phrases we find inflammatory or obscene are nothing more than contextual. That our words our reflections of our thoughts, as the Lao Tzu quote above says, and as such, can be modified and adapted to turn into any kind of habit/character/destiny we choose. In San Francisco, the court agreed. Chicago would not be so kind. Lenny was convicted on obscenity charges and sentenced to one year in court. The conviction was still on appeal – as well as numerous other obscenity charges from all over the country – when he died in 1966.

Lenny’s (only successful one time) defense of these arrests was that “obscenity” is contextual. That a word is a word, and only we can define their meaning. His trials even showcased this fact. Each trial seemed to have a different interpretation of the word “motherfucker”. What is offensive to women? Was it incestuous? Was it intended to denigrate the role of mothers in our society? Was it anti-marriage? Each court tried to get a handle on the words they had deemed offensive, and each court failed, yet still convicted him on the grounds of obscenity. From the time he uttered the words on stage, Lenny’s point had been that the meaning of the words lied with the listener. And the listener could try to infer the speaker’s intent, but the power behind it always lie with the listener. And if you heard a word and were harmed by it, it was the dark place that you went to within your soul with that word that was to blame, not the speaker.

At the heart of Lenny’s defense is the Lao Tzu quote at the start of this post. Lenny Bruce never denied that words had power. One needs to only look at the history of counterculture in this country to see numerous human casualties whose only act of aggression was the spoken word. Words can be enormously destructive, and that capacity for destruction can either be a chipping away of the detritus from an unfinished masterpiece, or it may be the laying to waste of a culture. Even this distinction is a matter of perspective. But Lenny also knew that the words he spoke flew in the face of conventional wisdom. The words he spoke challenged the narratives we as a society had built for ourselves. Our thoughts had become a specific set of words that were polite and words that were impolite. And the polite words existed to service our actions, which formed our habits, which built our national character, and pointed us in a specific destiny. And Lenny (as well as other social commentators) sought to combat that destiny (segregation, racial and gender inequality, repression, etc.) with their words. They attacked the problem at the root, asking each of us to examine our own thoughts and words, and possibly see the illogic behind them. If you want to collapse a monolith, you don’t chip away at it’s highest points; you blow up its foundation and let it implode on itself. Lenny was regularly placing those charges at the base of our collective psyche. And we took all his money, we silenced his voice, we degraded his sanity, and we eventually killed him for it.

If a society is willing to destroy a person over the words that challenge our collective narrative, what does that say about us as humans? Early in my marriage, my wife was trying to compliment me for something, and I convinced her to stop trying to make me view myself through a positive lens with the warning, “My self-loathing is a rock you will break yourself on.” My narrative was based on 23 years of history. It was such an ingrained part of my thinking that when her desire to make me feel positive about myself finally shattered on that rock, it didn’t feel anymore prophetic than “it gets dark at night” or “it gets colder in the winter”. We can try to convince ourselves that words are meaningless, but our words – particularly our internal narrative that we use to define ourselves – are all-encompassing. They define our actions and our character, for better or for worse. And we cling to those words, not because we believe them, but because we are them. But what happens when those words are wrong? What happens when those words tell you that you aren’t worth the love of the people who only want to love you? What happens when our words turn a good person bad, or turn a sweet person cynical, or turn the loving into the loveless?

To believe that the lesson of Lenny Bruce’s life is “we should be more fearless with our words” is to miss the point entirely. Lenny Bruce was as fearless with words and ideas as we’ve seen in contemporary society, and it literally killed him. That’s like saying the lesson of the legend of John Henry is “work out harder before competing against a machine”. It ignores the flawed element of the argument and places all responsibility on the victim. It’s similar to how we counsel women endlessly on tactics for avoiding rape, but no time counseling men not to rape. The lesson to be taken from Lenny Bruce is a lesson about our role in society, and our stewards of the words and narrative in that role. If the lesson is about fearlessness, it has nothing to do with the fearlessness of saying things, and everything to do with being fearlessly open to contradictory ideas. To be willing to accept the open discussion of different points of view on theology and morality and ethics our own weaknesses and hypocrisies, and to debate them and consider them. More importantly, to consider the possibility that our currently-held beliefs may be wrong, or may not be serving us as fully as we deserve.

We all have our own “rocks” that our words have created. And we all have people who love us and care for us who are regularly breaking themselves on those rocks. And we all have limitations that our own words put on us each day. If Lenny Bruce died for a good cause, it was to teach us to be brave enough to question the words that created those rocks. If Lenny died a martyr, he died to save us from ourselves.

Your insights are so powerful. Way to set charges at the base of your own rock.