Mr. Rogers Neighborhood: Final episode aired August 31, 2001

Tomorrow, I will mail a letter which confronts a bully. Not my bully, but a teacher who bullied my son last year in school. And when I recognized – a year too late – the damage this teacher had wrought, and when I realized that someone needed to address the issue with the teacher, I wanted to do it. Which is odd, because I’ve been combing my memory for any time in my past when I may have confronted a bully. I can think of times where I’ve fought back when completely cornered, and I can remember plenty of times where I forced a conversation through passive-aggressive tactics that highlighted my victim status. And I can think of times when I used sneaky tactics and diversions to get others out of difficult situations, but I’ve never been the one to stand bravely between predator and prey. And so the idea of sending a letter felt unlike anything I would ever want to do, yet I knew that it was something I needed to do. Partially because I do want to be the person standing between a predator and my child (even if it’s a year too late), but at its core, there’s a simpler desire. Sometimes, I just want to say what I feel, even if those feelings are ugly. Even if those feelings have negative consequences. Even if those feelings cause disharmony or escalation. Because I spend my days inundated with the voices in my own head, and they’re generally drowned out by the millions of voices from others, and all of those voices are trying to establish “who we are”. Except they’re generally establishing “who we wish to be” or “how we wish to be perceived”.

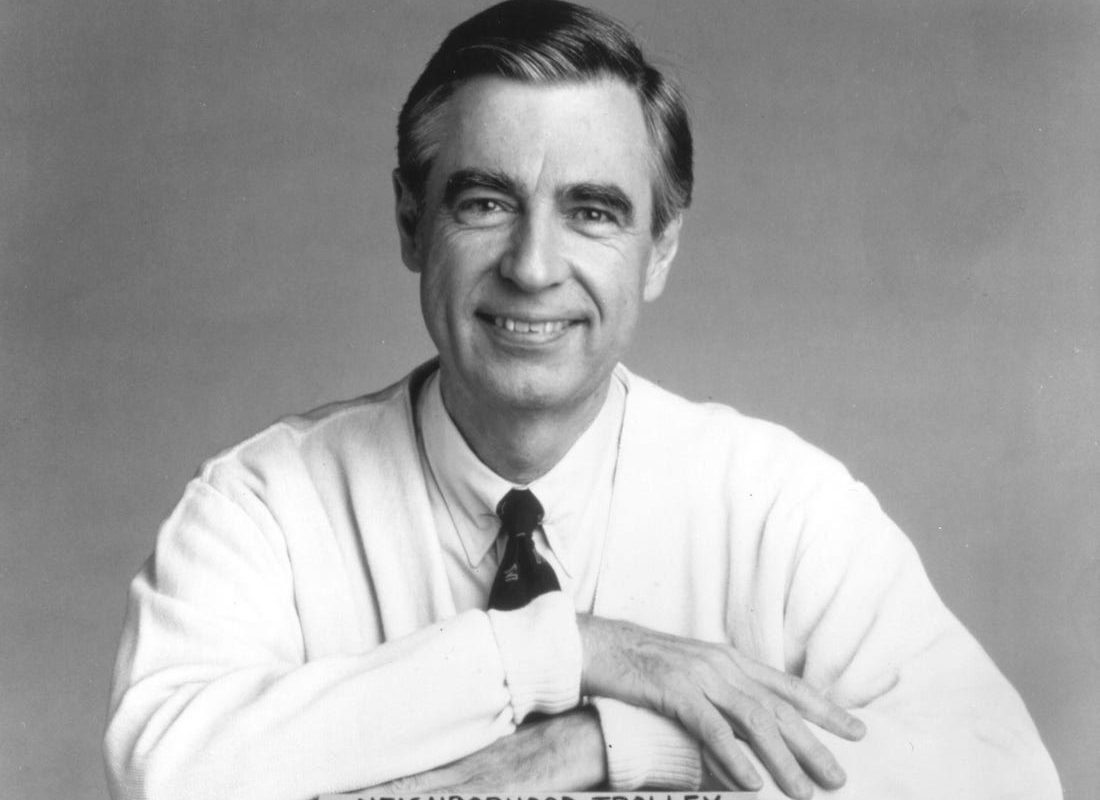

So few of us are the person we wish to be, that we almost don’t understand a genuine person when we see them. The advantage of that situation is that genuine people aren’t bothered by that in the least. Take, for example, Mr. Rogers.

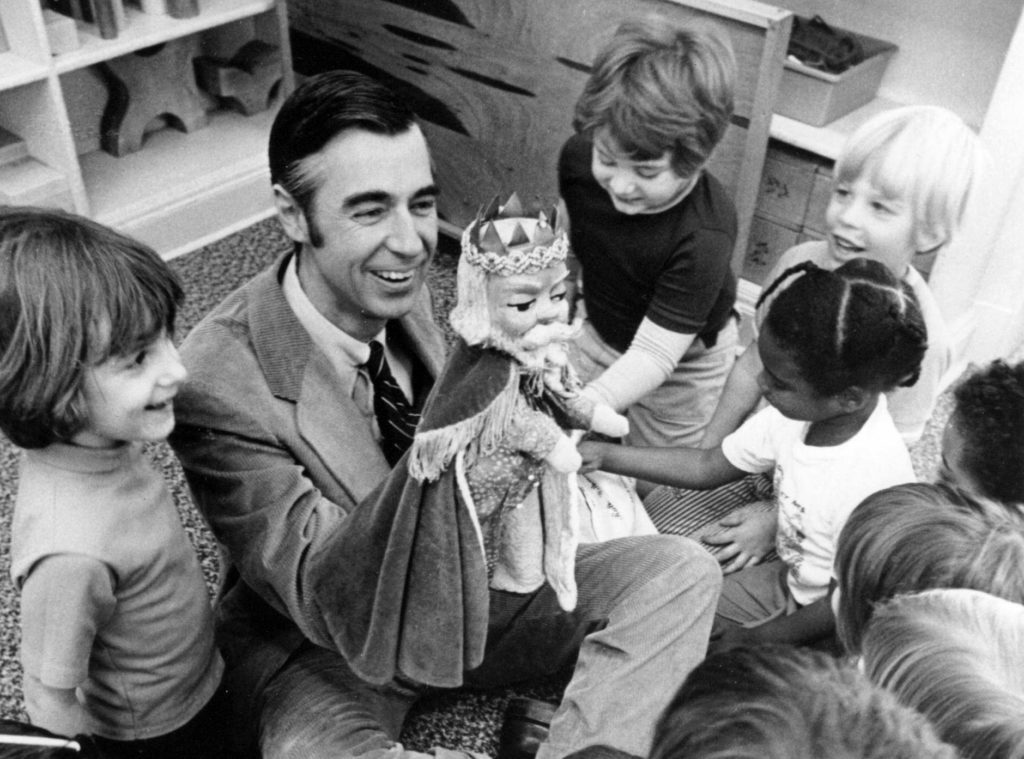

I watched Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood as a young child, but outgrew it before I could remember. Only snippets of it remained in my brain: the rituals of changing from suit to sweater and back, the cheesy “Land of Make Believe” sets, the puppets that seemed almost sickly compared to The Muppets on Sesame Street, the opening and closing routines. More than anything, I can remember turning it on as a pre-teen and watching for a few minutes, amazed at the awkwardness of the show. Mr. Rogers seemed almost alien-strange to me by the time I was “too old” for his show. He was unlike any adult on TV, and his manner was the polar opposite of any adult I personally knew. He seemed genuinely impressed by simple things like musical instruments and light bulbs and pre-school crafts and zippers. Not mesmerized or befuddled, but impressed. Appreciative. Taking the time to find gratitude for the things that kids and adults take for granted, but that his pre-school audience might not yet understand. More importantly, he took a similar interest in people. Occasionally, he’d wander out into the neighborhood and meet store owners and service employees and he’d treat every job as if it were sacrosanct. It was always just a formula interview (“What does a truck driver do?”), but Mr., Rogers’ reactions made it seem like the worker’s job was a covenant between themsefl and society. Which was unlike any adult I knew. Except, that is, for Fred Rogers.

It wasn’t until I was an adult and had read a few articles and saw a few retrospectives on Fred Rogers that I began to truly understand why he behaved the way he did. There was not just solid teaching theory behind it (Rogers had a degree in music education), but it was just genuine. Fred Rogers was the kind of person who refused to have a desk in his office because it represented a barrier between people. He was an ordained Presbyterian minister, and while he preached the greater, nobler tenets of Jesus (unconditional love, respect, concern and love for all without respect to status or station), he never pushed any religion. His religious beliefs showed through his actions, unbranded. Modern religious figures on television would never miss the opportunity toi brand their actions as a result of their superior faith, but Mr. Rogers never mentioned faith. He simply was the message he wanted to preach, and we never could understand him.

Over the last decade or so, I’ve seen viral messages pop up that tried to paint Fred Rogers in very unexpected lights. One claims that he was convicted pedophile who did the show as part of his community service sentence, and another claiming that he was a very deadly Navy SEAL with multiple confirmed kills during the Viet Nam War, and the reason he wore long sleeves was to cover the many tattoos on his deadly arms. The former claim is ridiculous and offensive on every level. The latter simply doesn’t pass any kind of muster when researched. Fred Rogers was never in the military, and was in his late forties during the Viet Nam War. But it’s the nature of these hoaxes that is so telling. The hoaxes weren’t novelties; they didn’t claim he had a weird collection of cars or a pet alligator. They were hoaxes specifically designed to explain his character. But why do we demand that a man as openly gentle and calm and caring as Fred Rogers have a twisted, morbid back story? Why do we only want to believe that a life of virtue and compassion can only be borne from great tragedy, or that it exists to camouflage the most horrifying of sicknesses? Why do we experience that difference between who we want to be inside, and who we present to the world? If the Mr. Rogers hoaxes have a genesis, its in the collective need to believe that the excuses we use to temper our outpourings of love are honest. That the reins we pull to temper our passions for things that benefit others are necessary. And that the vulnerability we allow by showing how much we can (and should) love is a weakness to be eradicated.

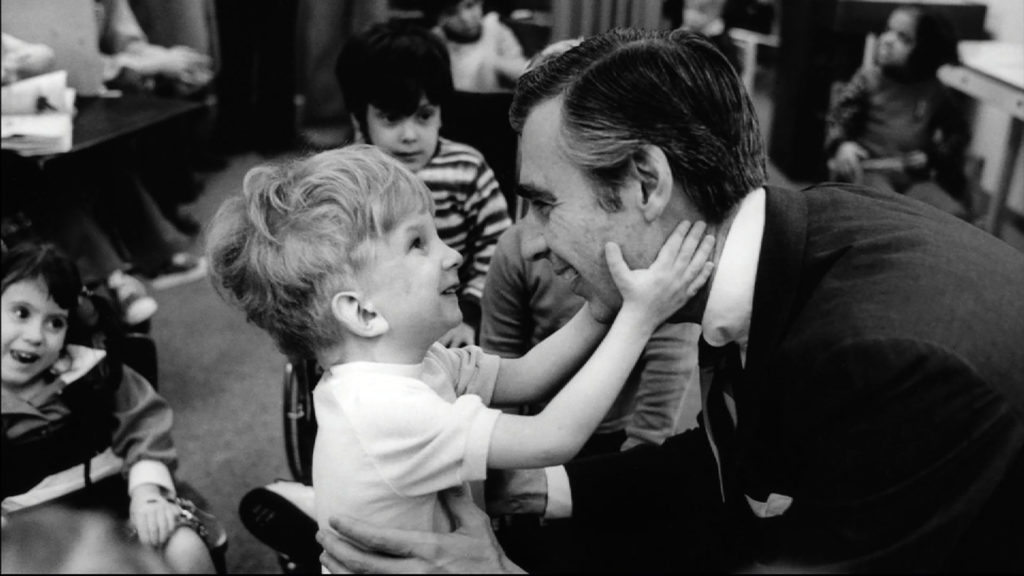

Personally, as I grow older I’ve begun to resent the difference between the person I feel like inside and the person I project out to the world. I’m growing increasingly tired of protecting my vulnerabilities to the point where it feels like I’m wearing a costume for my existence. I’ve grown tired of my fears and my shortcomings dictating my actions, and welcome the day when I can baffle the world by doing exactly what I think is right, without fearing how it will be received. When confronting a bully (on behalf of me, or on behalf of someone else) feels natural and easy, unencumbered by visions of consequences and possible outcomes. The most powerful actions seem to come from that alignment. In 1969, when Fred Rogers was asked to testify before the Senate Subcommittee on Communications to appeal their proposed halving of the budget for public broadcasting (as President Nixon had requested), he did not appear with charts and figures. He did not use data, profit/loss, or return on investment to sway the committee. He simply spoke from his heart. He spoke of concern for children. He spoke of fear. He spoke of a belief in a better world through caring and compassion and open attention to emotions. He spoke of validation. And sitting before notoriously-gruff Senator John Pastore of Rhode Island, he showed the kind of love that can only be shown through vulnerability. The moment was a pure and honest expression of who Fred Rogers was. And in the end, he gave the gruffest Senators goosebumps, and he not only saved the PBS budget, the Senate increased it by 10%. It was a classic moment, and not at all out of place with the Mr. Rogers we’d come to know.

The person we project to the world makes sense, I guess. It’s the version of ourselves who can’t get easily hurt. But when I think of Fred Rogers, I assume he would have stepped between my son and a bullying teacher right away. I assume he would be able to show and tell the people he loved how much he loved them. And I sense that Fred Rogers could have provided the same love and support and protection to himself. What a wonderful world it would be if that kind of behavior didn’t seem so unfamiliar to us.