THE INCREDIBLE MR. LIMPET: Premiered March 28, 1964

They say that great comedians exist in a constant state of outrage. Even the hackiest of comedic premises (airline food, socks disappearing from the dryer) are rooted in a sense of outrage. It’s a belief that the loss of a sock is so inexplicable and frustrating that they merit discussion. But these aren’t discussions designed to necessarily find answers; the power of comedy isn’t in resolution. Instead, the power of comedy is in allowing us the time to sit with an outrageous idea. In giving us the power and the incentive to consider it from any one of many perspectives. Comedy provides us with the opportunity to consider our outrage from multiple angles, including the angle which questions if our outrage is even reasonable. And by doing so, it inspires us to seek an understanding of the things that confound and outrage us the most. Hacky comedians and hacky premises nudge us lightly to understand shallow things. But great comedians push us to consider our beliefs and our morality and the philosophies that guide us. It’s why great comedians are so often stand-up comics; the very delivery mechanism is lecture-based, like in school. But sometimes, deeper considerations can come from comedic actors and their performances. And sometimes, those performances are as a cartoon fish.

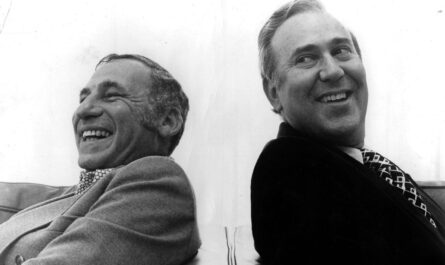

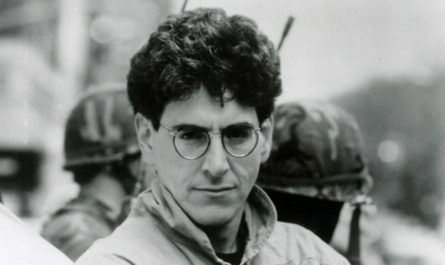

Don Knotts began his acting career as an enlisted entertainer during World War II. He would travel from base to base and ship to ship with a troop of entertainers and put on shows for the troops. Knotts was mostly a comedic actor and ventriloquist. After the war, he had performed on stage while trying to break into television. He had a small role on the soap opera Search for Tomorrow before being hired as part of the repertory company for The Steve Allen Show in 1955. Knotts would rise to fame giving fake “man on the street” interviews. In all of the interviews, he would play an excessively nervous man, stammering and sweating through the simplest of answers. He would over-react to simple questions and often lapse into slapstick moments brought on by nervous fidgeting. Audiences ate it up, and almost immediately Knotts was hired to play a similar role in the Broadway play No Time For Sergeants, an Ira Levin play that starred a rising North Carolina comedy sensation named Andy Griffith. When Warner Brothers Pictures decided to turn the hit play into a movie and a starring vehicle for Griffith, they also brought Don Knotts along to reprise his nervous/frustrated psychologist role. The friendship and impeccable comedic timing shared between Griffith and Knotts was obvious, and when CBS signed Griffith to play sheriff Andy Taylor in The Andy Griffith Show, Knotts was brought in by episode four. Knotts stayed with the show for five seasons, eventually leaving for a film career. His first film, The Incredible Mr. Limpet opened nationally on March 28, 1964.

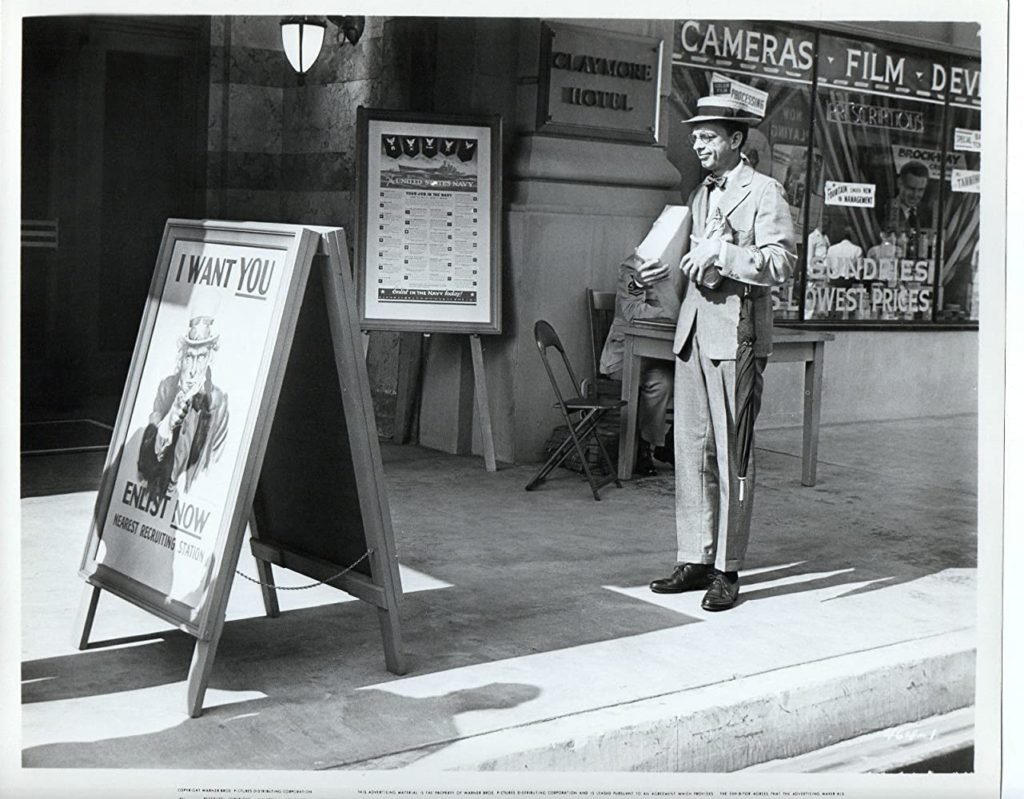

In the film, Knotts’s character Henry Limpet follows a similar trajectory to all of his other characters. Limpet is a nebbish, henpecked bookkeeper who is fonder of his pet fish than anything else in his life. He is a failure to his wife and friends, and after being rejected for enlistment in the early days of World War II, he goes to a pier at Coney Island to stare at the fish and accidentally falls in and – we’re never really told why – his wish to become a fish is granted. The underwater scenes were cartoons, directed by longtime Looney Tunes director Robert McKimson, and in those scenes the cartoon Limpet survived the typical indignities and confusions of all of Knotts’s characters. But he also eventually redeemed himself. Eventually, Limpet realizes that as a fish, he has a resounding “thrum”, a loud bellowing noise that frightens even the scariest of fish. And so he begins to use his thrum to alert the US Navy (who had rejected him for service) to the presence of German U boats off the American coast. By the end of the film, Limpet has ended the war, said good-bye to his wife, returned to the ocean with a female fish he loves, and eventually receives an officer’s commission in the US Navy. It’s a common story arc for the characters Knotts would portray throughout his entire career.

The thing that Don Knotts excelled at, and the thing that came through in every character was an overwhelming sense of vulnerability. All of Knotts’ characters seemed under attack at all times, and his body reacted the way nervous prey reacts – jittery and hyperactive and prone to over-reaction. What made the characters different was how they dealt with that vulnerability. Some would try to cover it with ridiculous amounts of bravado in different ways, others suffered it matter-of-factly, while Henry Limpet suffered it like the weight of the world. Even after becoming a fish, Limpet is vulnerable. He still requires glasses and can’t seem to shake off his human morality around sex and death and violence, which has no meaning under the sea. For Knotts, vulnerability was a stock in trade; he was born to showcase that. Born late in the life of immigrant farmer parents, his father was a paranoid schizophrenic who would self-medicate with severe alcoholism. In bitter rages, his father would threaten to kill young Don, chasing him around the farm with knives and cleavers; Don would learn how and when to hide to save his own life. Don’s life was spared by his ability to run and the pneumonia and heart attack that eventually killed his father when Don was 13. So for Don Knotts to play characters riddled with vulnerability was not only understandable, it was probably inevitable.

But we suffer from the myths we have about vulnerability. We believe that vulnerability (particularly in males) is a life sentence – that a man behaving like prey is weak and helpless and will always behave that way. We attribute a lot of shame to vulnerability based on those myths, but the reality is far from what we believe. The truth is, all courage is rooted in vulnerability. Every act of courage has to start from a position of vulnerability. Vulnerability is the wellspring from which massive changes often occur. Knotts, who suffered life-threatening abuse at the hands of his father (and later, worrisome poverty with his widowed mother), learned early that vulnerability was a state to be learned from, not a lifelong character trait. Vulnerability was a temporary series of lessons, and Knotts learned how to make something out of vulnerability. And so his characters did. We learned to laugh at Knotts’s characters vulnerability, but they always won in the end. As pathetically vulnerable as Henry Limpet was, he ended up a Commodore in the US Navy. As arrogant and incompetent as Barney Fife was, he ended up becoming a successful member of the Raleigh Police Department. Knotts’s career was almost exclusively vulnerable characters who eventually find their strength and are rewarded for it. Knotts’s comedy was a sense of outrage around our myths about vulnerability. Knotts would create a hilarious world where we laughed at the vulnerability of a man. And by laughing, we were forced to consider our beliefs and our myths about vulnerability. And Knotts’s career was a testament to re-framing that argument. To accepting vulnerability as a potentially positive force. To personifying the idea of overcoming the things that victimize us. It was Don Knotts’s comedic gift to the world, and it was a message as relevant from a man as from a cartoon fish.