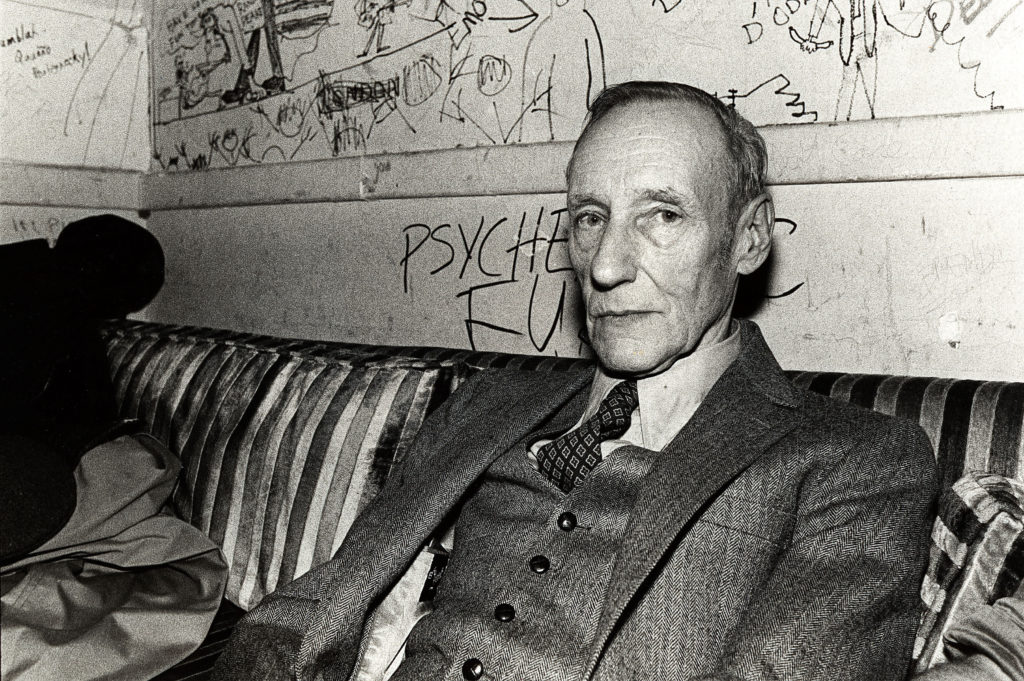

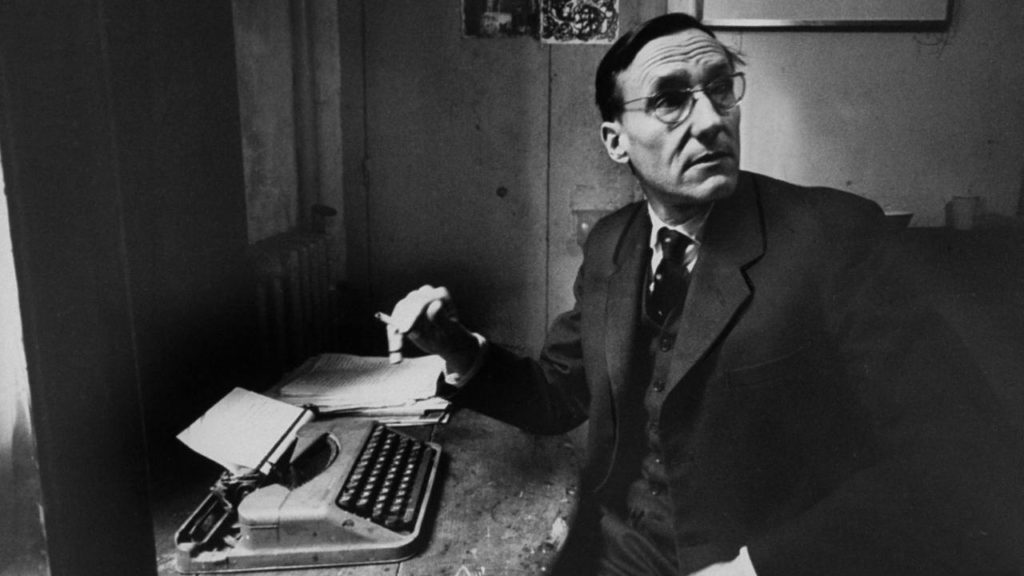

WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS: February 5, 1914 – August 2, 1997

I discovered William S. Burroughs at one of the two times people tend to discover William S. Burroughs. Generally, if you don’t discover Burroughs in a literature class, you discover him at a time in your life reminiscent of a Burroughs novel. Ask the latter group about their discovery of Burroughs, and it usually reads like a pulp novel. “I was living with a stripper and a pimp in a $300 a month two-bedroom above a bodega known for trafficking Ecstasy. I hadn’t slept in fourteen days when I found a copy of Naked Lunch in an alley…” I was definitely a member of the latter group. Burroughs is historically lumped in with the Beat writers, notably Kerouac and Ginsberg, but that classification is strictly a matter of historical – not literary – convenience. Despite the three being close friends, Burroughs was far from a Beat, stylistically or temperamentally. Whereas the Beat ethos was about experience and openness and acceptance, Burroughs was cynical and misanthropic. His quest for experience was entirely in his own head, and were often nightmarish and paranoid. Where the Beats sought to transcend, Burroughs sought to understand and condemn. If the Beats were the forefathers of the hippies, Burroughs was a forefather of punk. In the 80s, Wax Trax records in Chicago had a Kodak picture of Burroughs standing in a back yard with a broadly-smiling Iggy Pop. That image always seemed more sensible to me than the pictures of Burroughs and Kerouac and Ginsberg on the covers of Beat anthologies.

The truth is, even as I read Burroughs religiously, I had trouble connecting with it. At the time, a number of my friends were Lit majors, and they would regularly tout Burroughs as one of the most important writers of the 20th century. As their most “Burroughs”-ian friend, I was obliged to agree, but I never could understand why. By the early ‘90s, artistic themes like non-linearity and extremely graphic imagery had become commonplace in the art world, and while I appreciate shock value as much as the next person, it’s very easy to become inured to shock. Attempts to become more shocking usually just lead to a bored resentment. As I grew older, I found myself relating less and less to Burroughs’s literary work. His misogyny became so lowbrow and common, it was unbearable. The cut-up method he employed after meeting artist Brion Gysin always felt like more of a parlor trick. Compared to the crystalline text of his early dystopian works, the cut-up work felt almost tongue-in-cheek, like Burroughs was keeping ownership of his work at arm’s length. Even Burroughs’ defense of his writing and his life were so high-handed and painted with broad, fake erudition he seemed like a caricature. But through it all, Burroughs continued on a very specific theme, one that intrigued me and kept me coming back to his writing, despite having to wade through writing that felt intentionally abusive and yet half-hearted. Throughout his career, Burroughs sought to examine the paradox between living and creativity. Specifically, that the genesis of creativity comes from a destruction. The question he never satisfactorily answered was the one that intrigued me the most: what is it that must be destroyed in order to create?

Burroughs was in his late twenties when World War II broke out, and after being declared unfit for service, Burroughs fell into a life of crime and addiction in New York. By the time the war ended and the GIs were returning home, it was a new America. With the European and Asian infrastructures destroyed, a healthy American workforce, and a President who had led the Allied forces, the American middle class was created. It was an aberration of both capitalism and democracy, and within a decade of the war, Burroughs entire generation would be fully employed and flush with expendable income. But rather than use that freedom to find some kind of enlightenment, they would fall under the control of consumerism. Instead of creating a nation of free men, Burroughs noted, the middle class had created a nation under the control of the next shiny gadget. By 1951, Burroughs had left America for Mexico City with his second wife, Joan. One night, during a drunken party, Burroughs showed off one of his standard party tricks – “the William Tell routine” – where he would shoot a glass of Joan’s head with a pistol. That night, he missed and put a bullet straight through her forehead, killing her instantly. Burroughs would flee Mexico after some financial and legal assistance from his wealthy family, and he would spend a couple of years traveling South America in search of the hallucinogenic drug yage. He would also start writing. By 1953, Burroughs would write:

“I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would have never become a writer but for Joan’s death … [S]o the death of Joan brought me into contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and maneuvered me into a lifelong struggle, in which I had no choice except to write my way out”.

For Burroughs, death was one way to both acknowledge control and overcome it. As was addiction, particularly to heroin. For Burroughs, the trappings of a typical life – house, car, bills, and everything that helps us momentarily forget that the rat race has no finish line – were every bit as controlling as heroin or the guilt over killing a loved one. More importantly, the only way Burroughs saw to fight that control was through creation. And it wasn’t even a choice. Creativity wasn’t a method to overcome control, it was the only method. For Burroughs, it’s a terrible paradox, and helps explain his misanthropic tendencies. The things that give Burroughs’s life meaning (love, experience) are the very things that control him. The things outside of him that are important to him are the things that cannot coexist with creation. And Burroughs isn’t linear; it’s not that we need to destroy one thing to be able to create. To Burroughs, we choose between art and life, between creation and control, and choosing one ensures we can’t have the other.

While Burroughs’ misanthropy may run deeper than most people’s, his theme is a standard paradox for artists. The things in our life that control us become the well from which inspiration flows. Creativity in its purest form is a process of reconciliation; the artist consciously re-arranges elements of his/her world to provide a picture of the world in accordance with their dreams. We create worlds we wished existed. We create worlds beyond the traumas which limit us. We created worlds that are repaired, or were never injured in the first place. Even shallow creative efforts follow this rule; the poesy Facebook post praising a spouse in a troubled marriage is nothing more than an attempt to create a reconciled world beyond trauma. Because while Burroughs belief may be at the extreme end of the spectrum, the belief is common to artists. The act of living can be difficult, and it can be traumatic, and through it all we search for a way out. For Burroughs, that life needed to die, and he and the characters that doubled for him needed to destroy their lives to escape into some hinterland – psychic or otherwise. But life doesn’t need to be that linear. When we access our creativity, we’re destroying that part of ourselves that pushed us to be creative in the first place. Maybe it’s only for the length of the time we’re creating, maybe it lasts a bit longer. And maybe we never truly destroy the thing that controls us, but little by little we push back. For a moment at a time, we become the person we want to be, free of that control. It doesn’t need to be hideous or savage or shocking. It’s not a brutal death or a savage escape; it’s a life of tiny moments of escape.

As I’ve grown older, my fondness for William S. Burroughs has evolved. I’m nearing 45. I don’t want to live in a world so hideous I have no choice but to escape. I’ve neared that world; I’ve glimpsed it in moments. Burroughs had the direction and the goal right; we just disagree on the path.