A.A. MILNE: January 18, 1882 – January 31, 1956

When my wife and I were dating, one of the first Christmas presents I gave her was a blown-glass Winnie the Pooh Christmas ornament. The ornament was designed on the original E.H. Shepard illustrations, not the more cartoon-y Disney design. Years later, when she was pregnant with our first child, we were shopping for items for our son’s nursery, and I kept picking out Winnie the Pooh items. And nobody ever questioned why. To most of us, Winnie-The-Pooh is a natural choice for a child. It’s a story of innocence, and the happiness that comes from simplicity. It’s a good enough message for a newborn, but I’d read Winnie-The-Pooh at least a half-dozen times in adulthood. I’d chosen Christmas ornaments and decorations long before I had kids. And while I certainly appreciated the messages of simplicity, gratitude, and happiness, it represented something else that I don’t think I understood at the time. At their core, the stories of Winnie-The-Pooh are about telling stories; the medium and the message are the same. More specifically, the stories about creativity and how childhood and innocence affect that creativity. How growing up and losing our innocence also takes with it other benefits, among them our access to uninhibited creativity.

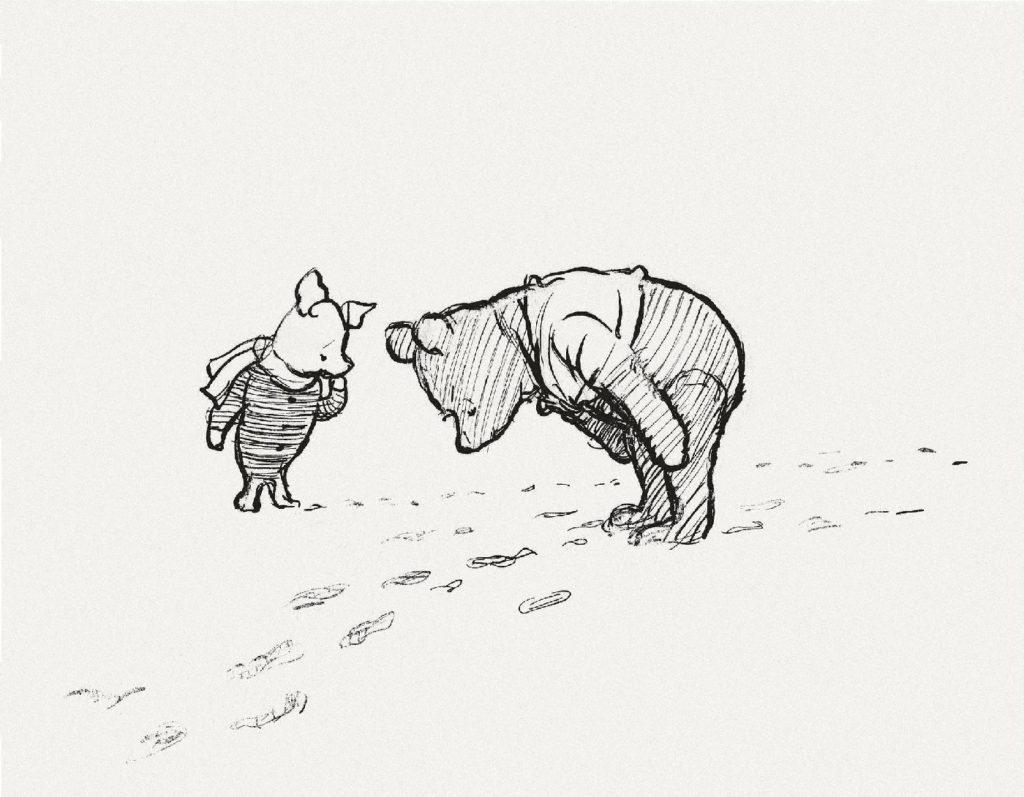

Winnie-The-Pooh had originated as a series of bedtime tales A.A. Milne had created for his son, Christopher Robin. When writing the book of stories, Milne framed the book through that dynamic. In the book, the narrator would begin a story to Christopher Robin, and then Christopher Robin would be magically swept into the story as both listener and character. The stories within Winnie-The-Pooh are all familiar: Pooh eats too much honey and gets stuck, Eeyore loses a tail, Piglet gets caught in a flood. Throughout the stories, Christopher Robin acts as both adult and child, advisor and student. He learns lessons in humility and gentleness, gratitude and simplicity. As the book draws to a close, Pooh has saved Piglet from drowning in a flooding rainstorm by turning Christopher Robin’s umbrella into a boat, on which the two sailed to safety. It was not a creative solution that anyone had expected from a bear with “very little brain”, and so Christopher Robin decided to throw a large party in Pooh’s honor. As Pooh groomed himself for the party, he began to feel pangs of anxiety. He began to wonder if he was worth the fuss. He began to wonder if his friends would remember his actions after awhile. Overcome by anxiety, Pooh created the “Anxious Pooh Song” in which he alternately called for a celebration of his name, but which unfortunately ended with his friends singing “Just tell me, Somebody – WHAT DID HE DO?” When he gets to the party, he is given a gift that makes him extremely happy: a Special Pencil Case, filled with pencils and erasers and rulers. It’s similar to a pencil case that Christopher Robin has in real life. The party ends, and Pooh and Piglet wander home and discuss how every moment of every day has the possibility to be exciting. The story ends with Christopher Robin asking for the next part of the story. The narrator says that more stories were available, “if you wanted it very much.” As Christopher Robin ascends the staircase to take his nightly bath, he asks if Pooh’s pencil case is nicer than his. “It’s just about the same,” answers the narrator.

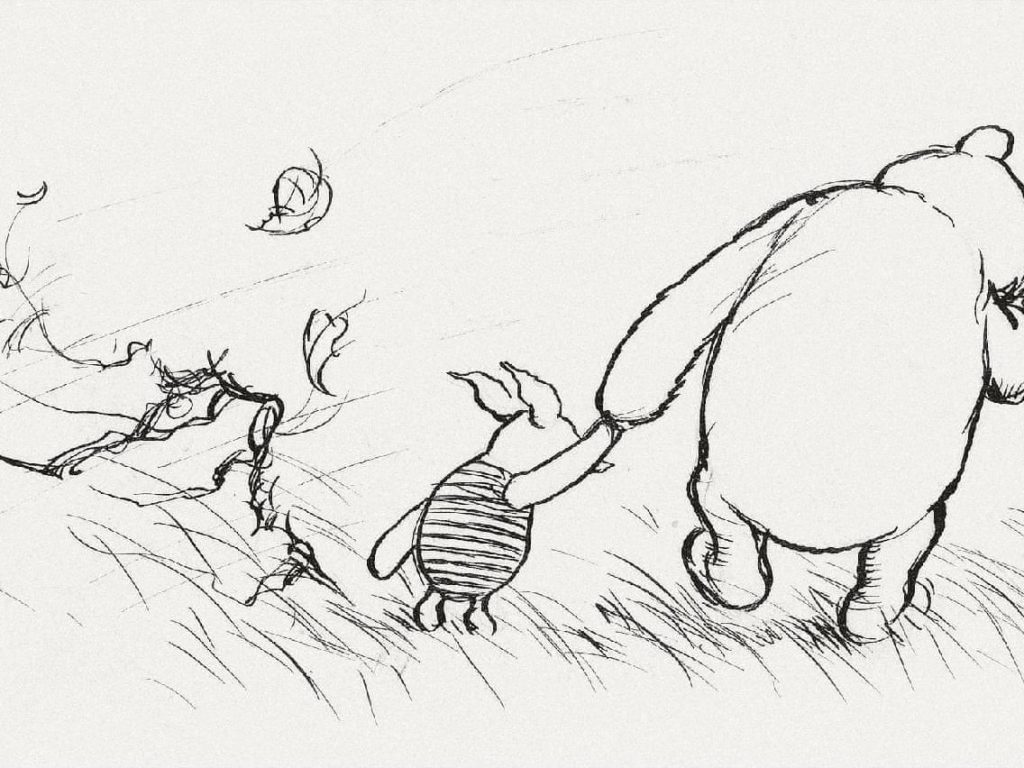

The ending of the book isn’t so much a nod to a possible sequel (Milne had no idea the book would be as successful as it was) as a charge to Christopher Robin and – by extension – the reader. The tales within Winnie-The-Pooh are so populated with Christopher Robin’s characters and his possessions and the reminders for his life, the story and the reader become intertwined. The events and items in our lives become totems upon which our stories can be told. And that’s the charge being put forth to Christopher Robin. His stories surround him and encompass him and his life doesn’t need to be separate from his stories. The pencil case at his desk is no better or worse than the Special Pencil Case within the story, and the goal is to understand that, and to avoid losing that sense. As we all grow older, we trade away access to our stories. We own fewer toys and more possessions. We trade joy for utilitarian functionality. We seek success through accomplishment instead of creativity. We seek certainty instead of wonder.And our lives become more about anxiety than creativity. Much like the Anxious Pooh Song, we seek recognition and reward, only to be forgotten or ignored; in the meantime, we overlook the enjoyment of creation.

I always assumed I’d be a writer. It was a “career” I’d flirted with throughout my life to varying degrees of success. But in a few short years, I was married, turned 30, found a career, and had my first child. And almost immediately, I embraced a vision of adulthood that kept me from accessing any of my own stories. I sold off music and books to make room for the baby. I gave away guitars and started focusing intensely on work. My attitude was much like Eeyore when Pooh was given the Special Pencil Case. “This writing business. Pencils and whatnot. Over-rated, if you ask me. Silly stuff. Nothing in it.” And very quickly, the stories I had to tell stopped. But I wasn’t prepared for the after-effects. With the stories gone, the things that could be turned into stories quickly became possessions – inert and functional. Art became entertainment. Passion was replaced with numbness. And slowly, my sense of wonder was replaced with success metrics. Life was measured by what I could accomplish, and what I could provide. Pay raises, new positions, making sure the bills were paid, doing what was asked of me, supporting my family’s dreams… these became my guideposts, and I never needed to examine anything any deeper than “was the task completed?” This is a good formula for a productive life, and possibly for a lucrative life, but not necessarily for a life filled with wonder.

When we grow into adulthood and accept the responsibilities that come along with it, we need to examine what must be sacrificed to live up to those responsibilities. Often, we rid ourselves of our passions as easily as we rid ourselves of toys we’ve outgrown. In the end, we rid ourselves of the freedom to tell our stories. But life shouldn’t be an exercise to be mastered. If we’re open to it, our lives become the source of our stories. If we’re open to it, we find magic in the moments of our lives, not from an escape we plan and save for, and experience during the two weeks’ vacation we get from our jobs. If we’re open to it, we view life the way Pooh and Piglet did as they walked home at the end of the party.

“When you wake up in the morning, Pooh,” said Piglet at last, “what’s the first thing you say to yourself?”

“What’s for breakfast?” said Pooh. “What do you say, Piglet?”

“I say, I wonder what’s going to happen exciting today?” said Piglet.

Pooh nodded thoughtfully. “It’s the same thing,” he said.”

What can happen to us that might be exciting? That might be worthy of our stories? All of it. If we’re really open to it.