MARK ROTHKO: September 25, 1903 – February 25, 1970

The irony of this project is that it directly correlates with low points in my life. I can look back at the calendar dates when things were written and remember what was happening at the time that made me grasp gratitude as a saving grace. When I started writing again in February, it was a year of COVID and a January of violence and polarization as we watched an increasingly-fragile democratic experiment hurtle ever closer to irrelevance. It’ feels like I can’t experience many human interactions that aren’t overwhelmed with anxiety and depression, or include someone completely flying off the handle at the slightest provocation. This is life during a period of constantly exposed nerves, and so the need to remember “the good things” seems reasonable; but why write about it? It’s hard enough to find time to spend with the people I love. Much of my time is spent managing erratic working relationships and clients who are frustrated by things that have little to do with me or my work. Getting out of the recliner to do anything else feels almost like an emotional impossibility. And yet, when these periods hit, I find myself writing again. And drawing again. And (sometimes) singing again.

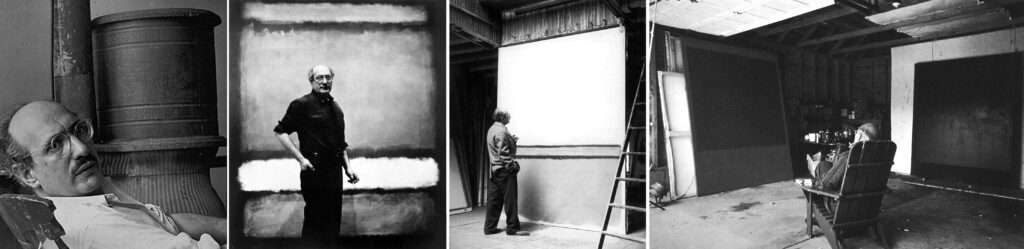

The first time I truly noticed a Mark Rothko painting was in 2001 at the Pompidou Center in Paris. My wife and I had been sightseeing all day, and it was late in the evening and we hadn’t had dinner. I was tired and hungry, and in one of the contemporary wings, a bench had been placed directly before a large Rothko painting. I don’t even recall which one it was, and quite frankly, when viewing a Rothko that fact is pretty irrelevant. It was not my first Rothko; the Art Institute of Chicago owned multiple Rothko’s, but I always blew by them on my visits. Something about these giant blocks of color felt ridiculous to me. I ignored them with the shamelessly naive mantra: “Anyone can do that.” But that night in Paris, I took a break and allowed myself to look at this large painting. And I noticed the depth of the paint, which had been layered so deeply that the texture of the canvas was imperceptible. I noticed how the three blocks had an intensely rich gradient between the colors, and that the blocks were not monochromatic at all, but ever-so-slightly rose and lowered in saturation.

And then I remembered my very first apartment. Ten years prior, I had rented a tiny studio apartment in Chicago’s north side. The bathroom window looked out onto a brick wall. I was young and impulsive and abusing alcohol and drugs. I had flunked out of college, taken a job assembling ventilators at a hospital, and was basically conning and lying my way through life so I wouldn’t have to confront all of the self-loathing that I carried like a pack-mule. The apartment was an attempt to prove to a girlfriend that I could be a (vaguely) responsible adult. It felt more like a prison. Except for the handful of times people came over to visit, I spent most of my time in that apartment eating macaroni and cheese out of the saucepan it was cooked in, worrying about how I would make next month’s rent, and drinking and drugging myself to sleep. I had cheap bamboo blinds that barely blocked the sun, and I would get so paranoid at times that I would hide in the bathroom because nobody could see in that window. And that was what came back to me as I stared at that Rothko. Not the memory of staring at a brick wall, but the feelings. The hopelessness. The shame. The sadness. The isolation. And suddenly, on a spring evening in Paris in front of a large Rothko painting, I was processing emotions from a decade before, feeling things I hadn’t felt in quite a while, as if the painting was some kind of portal to a previous emotional state.

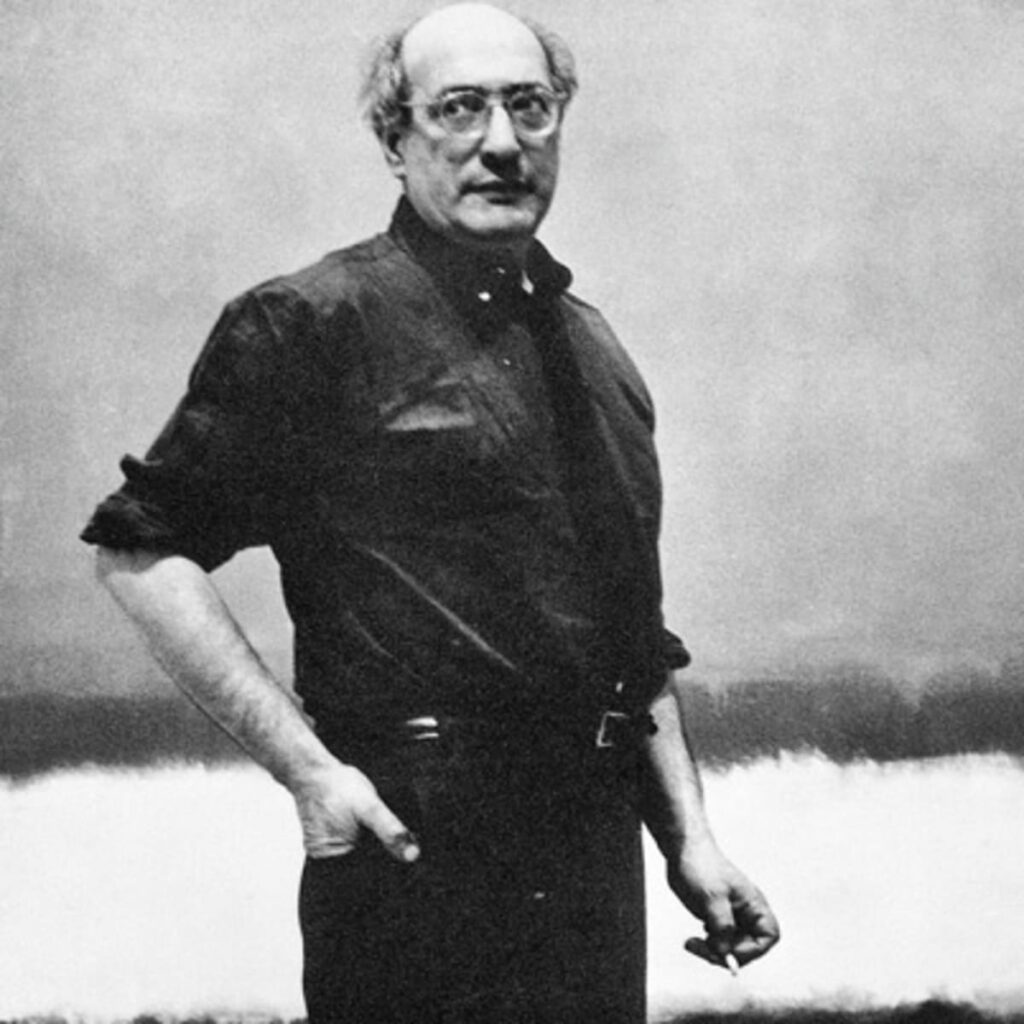

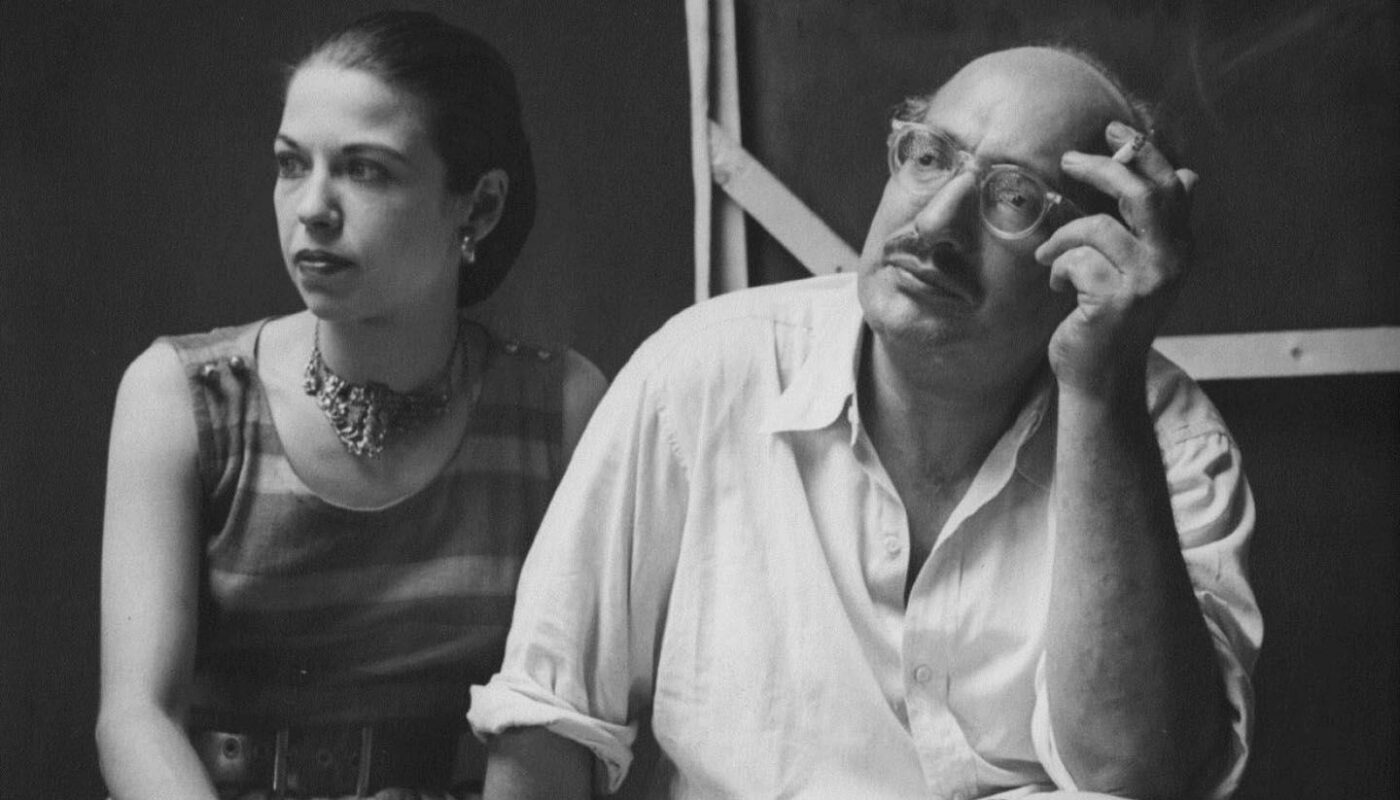

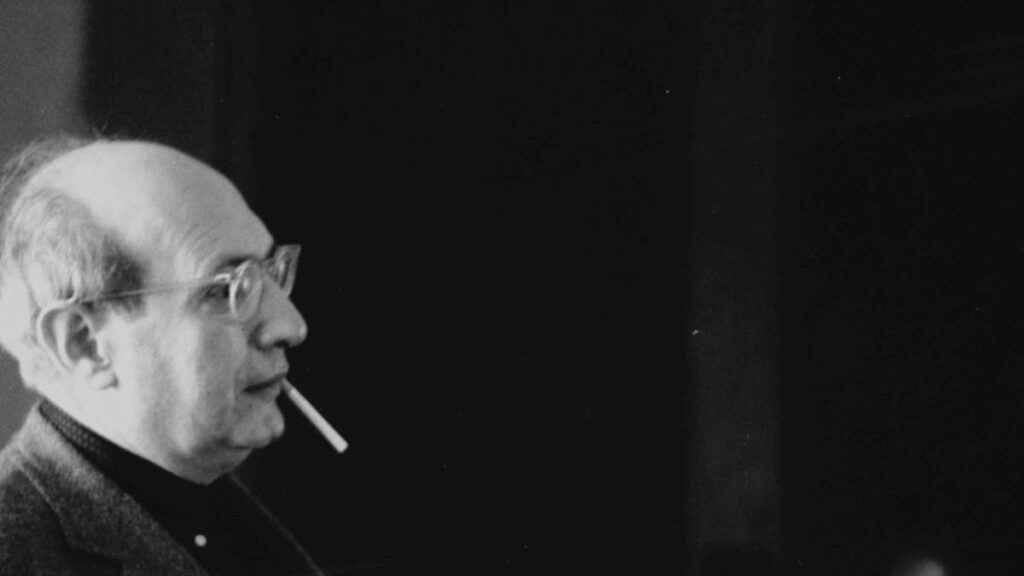

That transformation was Rothko’s intent all along. Born Markus Rothkowitz in Dvinsk, Russia in 1903, he emigrated to the Pacific Northwest with his family as a child. After a couple of years studying at Yale, Rothkowitz dropped out and moved to New York to study art, shortening his name to “Mark Rothko” in the process. He bounced from style to style, as most young artists do, ever reflecting his most current inspiration or mentor. It was only when he discovered the color field paintings of Clyfford Still that Rothko’s work began to take its most notable form.

Rothko quickly moved away from figurative art and began to focus on pre-attentive processing aspects like color, light, contrast, and form. Despite an unwillingness to brand himself with a label as a member of any artistic movement, he was regularly referred to as an abstract expressionist because abstract expressionism focuses on the emotions created by reality, not the re-creation of reality itself. As Rothko said of his work:

“I’m not an abstractionist. I’m not interested in the relationship of color or form or anything else. I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions: tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on.”

Rothko’s work was an examination of our subconscious reactions to color. He was curious about how colors stoked our natural emotions, how they inspired memories. His work was both primordial (relying on colors that were reminiscent of sunrises, sunsets, oceans, and darkness) and conditioned (blocks resembling windows, doors, or jail cell bars). He used contrast to brightly-color the boundaries of each painting, and the intensity of the blocks seemingly invited the viewer to dive in and get lost in their depths. Over the decades, he sought the perfect colors and arrangements to evoke emotional ranges. The Rothko Chapel on the campus of The University of St. Thomas in Houston consists of over a dozen large purple-gray panels. Rothko’s own son described his disappointment at how “boring” the panels seemed when he first saw the chapel. His disappointment was soon dashed, however; he sat on one of the benches to take them in, got lost in his thoughts, and suddenly realized that an hour and a half had passed.

The lesson I learned from Rothko’s work is that “it takes time”. It’s a lesson that applies to artists and audiences, alike. The only reason I’d never experienced a Rothko painting before was that I simply had never allowed myself the time required for the experience. I rushed past multiple Rothkos over the years on my way to more figurative works – notably Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks”, which I would stare at over and over and over. But my goal was always to try to understand what Hopper was trying to say; the emotions, the feelings, and the truths beneath that message were just inadvertent results of any attempts to “understand” the painting.

The hurdle during times of stress or depression is to allow myself time. During positive periods, I’m generally too busy to stop and take a moment for anything creative. But when the chips are down, I do very little with the time I have. In the last few months, I’ve had entire days where I accomplished nothing but sitting and worrying about all of the things I should be doing. So when I force myself to do something creative (like write about gratitude), I’m not searching for answers or understanding – despite all outward appearances. I may be writing an explication of some artistic triumph or historical feat, and I may be correlating it to something from my life, but what I’m actually doing is giving myself time. Time to remember. Time to feel. Time to re-live the emotions that neither a busy nor a depressed life make room to experience. During the writing of this post alone, I have gone off-track in my thoughts at least a dozen times and become lost in the emotions of random events from the last fifty years of living. It’s the reason we create art, the reason we experience art, and the reason we need art.

We just need to give it the time it requires.