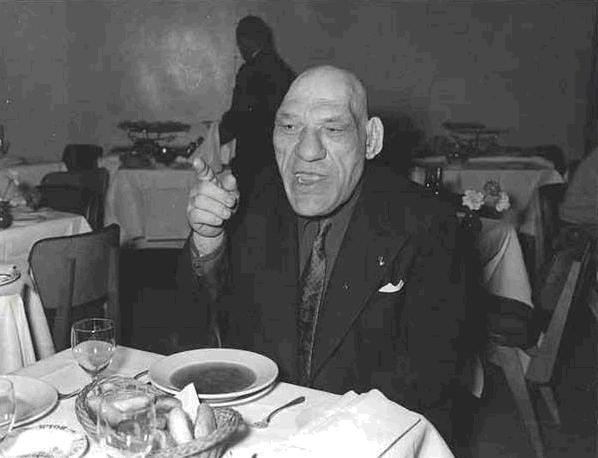

Maurice Tillet: October 23, 1903 – September 4, 1954

When you’re always the biggest person around, you learn that the world will always treat you a little differently. I was over 11 pounds at birth. I was always the tallest kid in school, and outweighed most of my classmates. As a kindergartner, I was frequently mistaken for an older child. I grew taller than my older brother by the time we were teens. I was taller than most of the adults I knew by the time I could drive, and unlike most gangly teenagers, I was neither lean nor lanky. In high school, I need a helmet big enough to cover my size 8-1/4 head, which my high school was able to borrow from the state athletic association – because nobody else was using it. In the entire state. Of Illinois. And as I became an adult, I grew used to kids staring at me everywhere I went. I got used to people always commenting on my size everywhere I went. I got used to smaller men picking fights all the time. I got used to the good-natured jokes and even the passive-aggressive ones. When I met my wife in my late twenties, she couldn’t understand why I was so uncomfortable with my appearance but after a few years of everyone mentioning things she didn’t think of as atypical (“He’s really tall!”), she came to understand how being almost constantly singled out can eventually lead to a skewing of self-perception. And certainly, being singled out for being overly tall or overweight aren’t nearly as damaging as people singled out for their race or for their gender or for a disability. But there is a similar process at play, because part of the assumption about me is not just that I look different, but that these looks indicate something specific. After years of hard work in my career, I have found a certain amount of credibility as a thought leader. I’ve published a few things, been used as a resource for a couple of other books, and I’ve spoken at a number of industry panels. But I find that meeting people in person changes the dynamic. They almost seem taken aback, as if they shouldn’t be taking advice from someone who looks like me. And it has limited my career. As I get older and it happens with more frequency, I find myself more and more hesitant to leave the house and meet people. When you physically resemble Shrek, as I do, facing people’s perceptions of you is rarely kind. Even less so, I would imagine, if you were Maurice Tillet – the inspiration for Shrek.

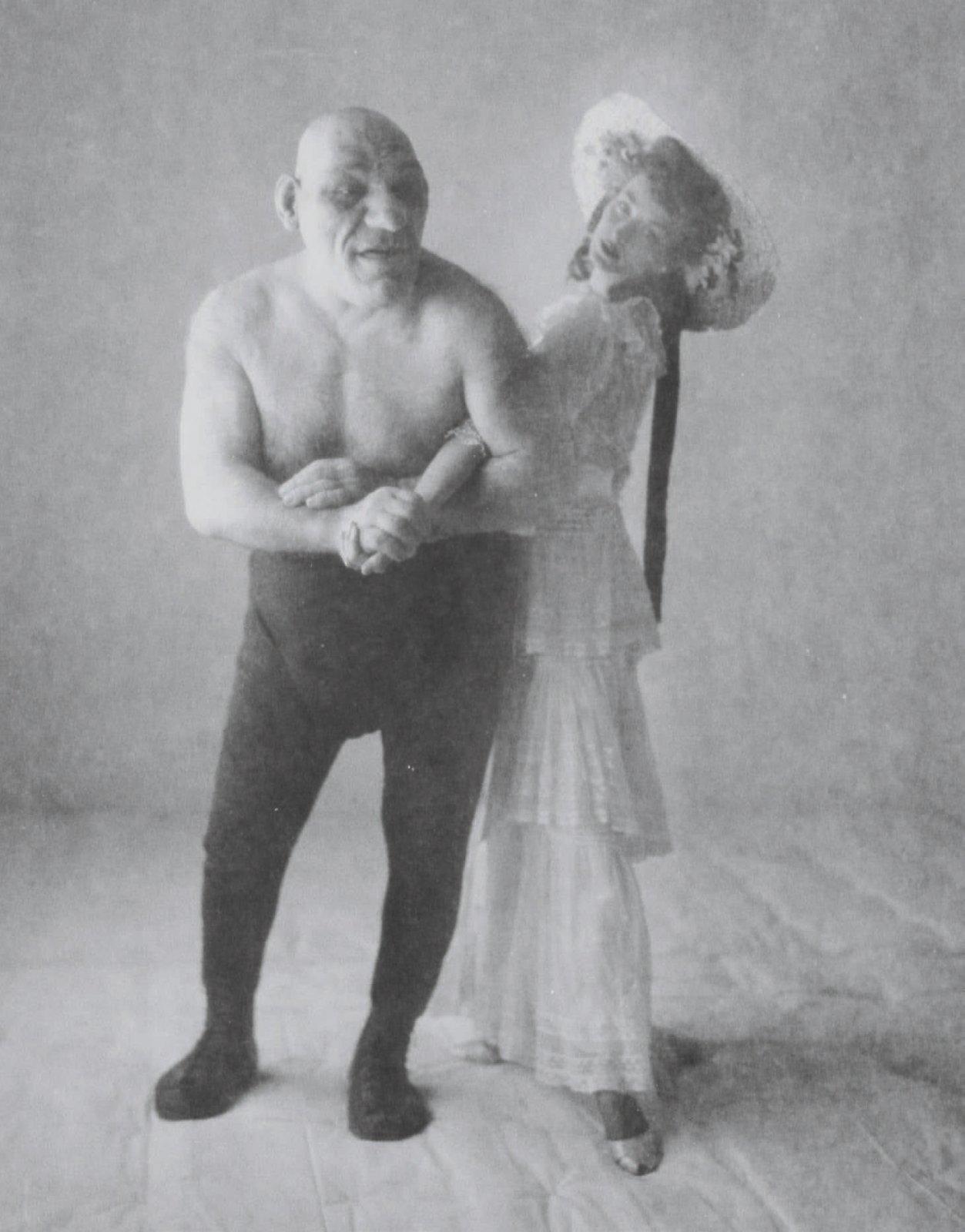

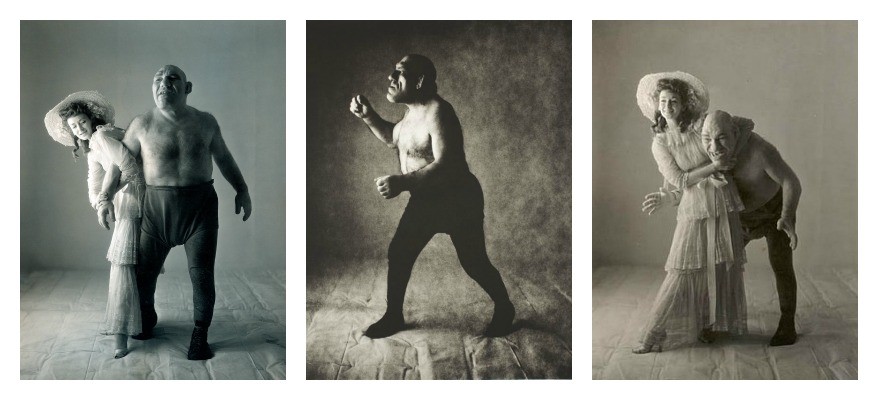

I first heard about professional wrestler Maurice Tillet in the early 90s. It was the period of late college for many of my friends, and a curious period of armchair diagnoses about why I might be so big. Every pre-med I knew seemed to run across a genetic abnormality in their studies and diagnose me with their affliction du jour. One of my friends was studying acromegaly – the overproduction of the pituitary gland due to a benign tumor, which causes intense bone density and growth – and decided that was what I had. He pulled out a picture of Maurice Tillet to show me how our heads were similarly over-sized. I was offended, because Tillet’s head was clearly oversized, but in a wild, somewhat deformed way, while my head was simply “big” – a scaled up version of a typical head. But my friend was certain he’d figured out why I was so big. And it hurt. It hurt mostly because in the photograph, Maurice Tillet looked grotesque and monstrous, and I realized that even my close friends viewed me that way. And so when I was combing some library’s stacks a few months later, I stumbled across a book about the pioneering days of modern professional wrestling, and inside was a few brief blurbs and photos of Tillet. Most were action photos of Tillet in the ring. In one, another massive wrestler tries to get his arm around Tillet’s throat in a choke hold, but Tillet’s head is simply too large for the opponent to gain leverage. But one page included an Irving Penn portrait of Tillet with early modelling icon Dorian Leigh under his arm – the former stripped to the waist and in wrestling tights, the latter dressed in a fashionable dress and high heels. It was a decade after the movie King Kong had first been released, but the imagery was unmistakable. Leigh was the ideal vision of normative beauty, Tillet the threatening monster.

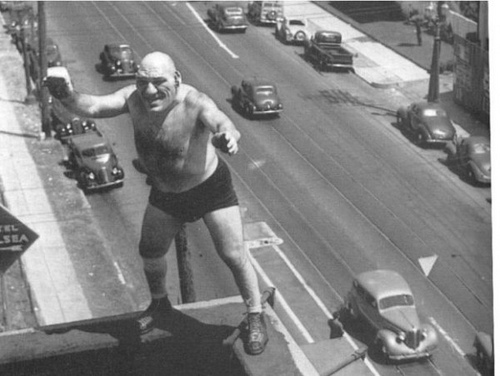

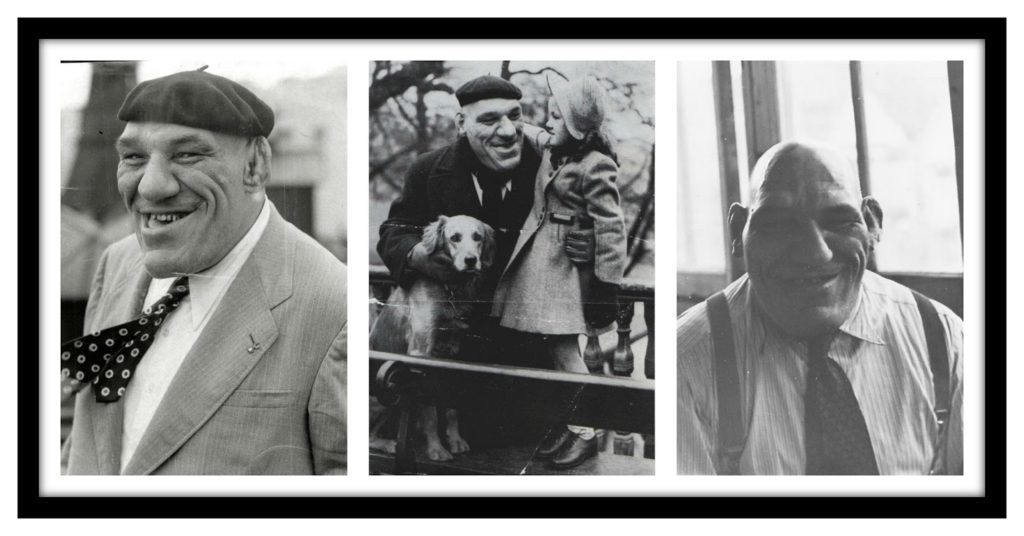

But the text of the book mentioned a few things that surprised me. Namely, that Tillet was an avid reader and a poet. At the time, I was an avid reader and a poet. Tillet had dropped out of school, but remained an enthusiastic learner, considered a polyglot by most people. I had dropped out of college early on, but hadn’t slowed down my learning any during that time. (I actually supplemented my meager income by writing term papers for my friends in college.) Finding information about Tillet was next to impossible until 2001, when Dreamworks released the movie Shrek. When the movie came out, more than a few people took jabs at me about my resemblance to the title character. But as soon as I saw him, I knew he’d been modeled after Maurice Tillet. By that time, the internet made it easy to find out that Tillet had been raised in Russia and France with a relatively normal childhood. In fact, his appearance as a young was so angelic, he had been nicknamed “The Angel”. He was a teenager when his acromegaly began, and the rapid growth of his hands and arms and head forced him to drop out of school. He was studying to be a lawyer, but he was told that his appearance would make that impossible. So, he enlisted in the French Navy as an engineer, where he served for five years before being dismissed from duty because of his appearance. Tillet was 34 when he was discovered by a wrestling promoter while travelling through Singapore. Tillet moved to Paris to train for a career as a professional wrestler, taking full advantage of the city’s cultural offerings. When invited to parties, people would assume Tillet would be a savage among gods, but Tillet surprised them. Instead of wine or cigarettes, Tillet drank only tea, and would infrequently nibble on a cookie. Despite a garbled voice from his condition, Tillet was a thoughtful and intelligent man who spoke 14 languages, which surprised everyone who met him. Much like Shrek, Tillet was a man who learned to prefer being alone instead of regularly dealing with the lowered expectations about him.

But this is not to say that people point out differences with a cruel intent. The reality of neuroscience is that our brains are wired for survival, and part of that wiring is to recognize anything unique. And to assess whether it is a threat or not. So it’s unrealistic to assume nobody would notice a giant man with a head twice the size of a normal head. Certainly, the evolution of a civilized society should teach us not to judge someone on their appearance, but sadly, as civilized as we may wish we were, our brains still exist on a very basic survival level. It’s our sad curse as humans; while the base functions of our brain may process something as a threat, our higher, upper cortical functions haven’t learned to not judge it in some way. It’s sad enough to classify a poet and polyglot as a freak, simply because the signs we see are unique and rarely charted in our memories. But the real sadness is when the poet and polyglot – after years of being treated like a freak – believes it himself.

What happened to Maurice Tillet isn’t unique to any of us. Tillet wanted to be a lawyer. He was an artist with a love of academia. (Tillet submitted to a study of his physical features by famed Harvard anthropologist Earnest Hooton, who helped define the colonial roots of racism. Hooton posited that dominant cultures use their standards to define the culture, thereby making anyone outside of that standard “inferior”. Tillet agreed to work with Hooton because of his admiration for the man’s academic work; the only payment Tillet requested – an autographed photo of Hooton.) But he agreed to spend his life wrestling in smoky arenas, billed as “The Aberrant Animal”, “The Human Monstrosity”, and “The World’s Ugliest Human”. Because when you’re told you’re a freak long enough, eventually you start to believe it.

Perhaps I felt an affinity for Maurice Tillet because of a life being singled out for my size. But in reality, Tillet represents the most damaging – and limiting – part of all of us. Because almost all of us struggle in one way or another to meet that standards which our cultures bear. We’re not pretty or smart enough. Or we’re too pretty or too smart. We’re the wrong color, the wrong gender, the wrong sexuality, the wrong religion. Our voice is too high, our fashion is to outdated, our bank account too empty. In some way, almost all of us are outside the norm in some way, and in that way, “inferior”. And we’re reminded of it regularly. But just because the place in the human brain that identifies differences is intended for survival doesn’t mean that anything outside of those standards needs to die. But it’s an exhausting war. Maurice Tillet killed his dreams because they were a threat to other people’s survival instinct. He shifted his life to live in a place where he fit more comfortably with everyone else’s standards. In making himself into a monster, he gave up the fight. I can understand why, but I also dream of a time when he wouldn’t need to. Because at 45, I can reflect on dreams of my own that have died from embarrassment. I’ve buffed down shinier parts of my personality and quieted some of my creative voices. And for a man of enormous stature, I’ve spent a majority of my life trying to shrink away. And like Maurice Tillet – or Shrek, for that matter – at the end of life, if we are truly successful at killing the parts of us that don’t meet the norms of society, we’re left with a sad epitaph: “I did my best not to upset strangers by being alive.”

So I think of Maurice Tillet as I contemplate the next phases of my life, each one requiring me to embrace parts of myself that have been ignored or lie dormant or withered from neglect. And I remind myself what it means to be different, and to prepare myself for what backlash that might create. And I hope that when the time comes, I’m strong enough to be who I want to be. I’m a giant man, but I hope I’m strong enough.

I am forever on the hunt for new details on Maurice Tillet. You have a very insightful, and insider take on Maurice. I study him almost continually and continue to be impressed by the quality of the human being he was. I can tell you with absolute certainty no one on earth knows more about him than I do. He played the monster, in the ring, and in film, which enhanced his popularity. It was however the quality of his character, his athleticism, and his intellectual prowess made him a household name. From every indication, everywhere he went, he became a beloved favorite of the fans, and for every last person that got to know him. Far from recoiling from the public eye, he put himself out there, and when people stared, he called them over. First I would like you to take a look at my site to understand the real Maurice Tillet that resides behind the wrestling hyperbole, here: http://deathmaskofmauricetillet-theangel.blogspot.com/2012/10/everything-maurice-tillet-french-angel.html. Next I would like to communicate and know more about your story. My address is thefrenchangeldeathmask@gmail.com Thank you for sharing your story and finding interest and commonality to Maurice's.