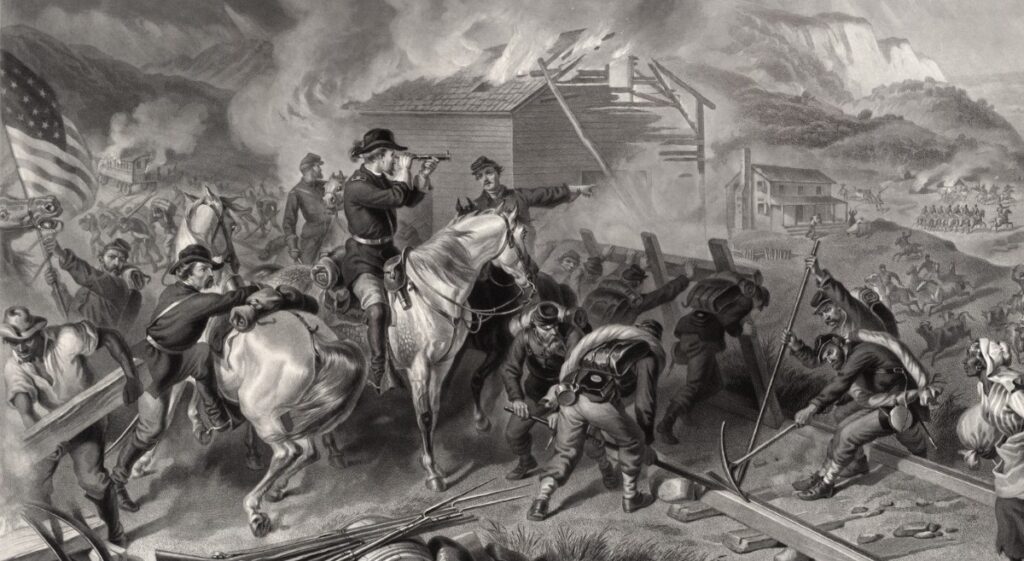

SHERMAN’S MARCH TO THE SEA: Ended in Savannah, GA on December 21, 1864

“The best way out is always through.”

Robert Frost

The legacy of General William Tecumseh Sherman is a study in perspectives. To military historians, he is the first modern general. To Southerners, he was a brutal maniac. To the descendants of slaves, he was a modern Moses delivering their ancestors from slavery. To readers, his memoirs are some of the most thought-provoking military memoirs ever written. I am descended from a long line of central Ohioans, and Sherman (born and raised in Lancaster, OH) has always been a “proud son” of this region. Which made my interest in him understandable, but admiration for him a curiosity. I am, by nature, anti-war. Which is not to say I am a pacifist, because I believe in the individual right to aggression. However, I dislike war as a requirement of the social contract. And I dislike it as an option for settling policy disputes. These are just my opinions, and I regard them as such, so it’s curious that I would find myself fascinated by a military man. Particularly one know for his brutality.

While Sherman is now known for his March to the Sea, the anomaly in Sherman’s life story is the unexpected break he took during the Civil War. Having been a young graduate of West Point, Sherman assumed he would live a military life. Whether it was bad luck or a naturally-nervous disposition, he was one of the few graduates of his class who saw no action in the Mexican-American War. Frustrated with the military, Sherman resigned his commission without having seen battle. He then became a bank manager in speculation-crazy San Francisco, a position which further unnerved him. During this time, he was involved in two shipwrecks. As crime in San Francisco became rampant, the Committee of Vigilance was formed to punish crime, and they named Sherman major general of their militia. Sherman developed stress-related asthma, and the constant fraying of his nerves forced him to leave with the first good job offer. That job offer was to be superintendent of a military school in Louisiana (now Louisiana State University). It was a position perfectly-suited for Sherman – easy on his nerves and cerebral, it allowed him to think about military action without any of the actual stress. However, Sherman was loyal to the United States, and as the South began secession activities, Sherman resigned his position. At first reticent to join the Union Army, Sherman finally relented and was commissioned as a colonel. His first battle was The Battle of Bull Run, where the Union was soundly defeated. Sherman was hit (but not severely injured) by two bullets. Immediately after, he began to question whether he was fit to be a leader.

In the midst of his self-doubt, President Lincoln promoted Sherman to Brigadier General. The promotion, coupled with the internal dialog was not good for Sherman. Now commanding the militias of Kentucky, a state partially held by Confederate forces, Sherman began to panic. He regularly questioned the ability of his forces. He overestimated the number and abilities of the Confederate forces. He panicked. Meetings with superiors went poorly enough that the press got wind of Sherman’s nervous behavior and reported on it. There were reports that he was manic, hallucinatory, suicidal. Finally, he begged to be relieved of command. Finding him unfit for duty, the Army swiftly complied. Sherman returned home to Lancaster and had a nervous breakdown. For six weeks, Sherman stayed in his family’s Lancaster home while the northern press savaged him as a lunatic or a coward. Or both. They were labels he would wear for years.

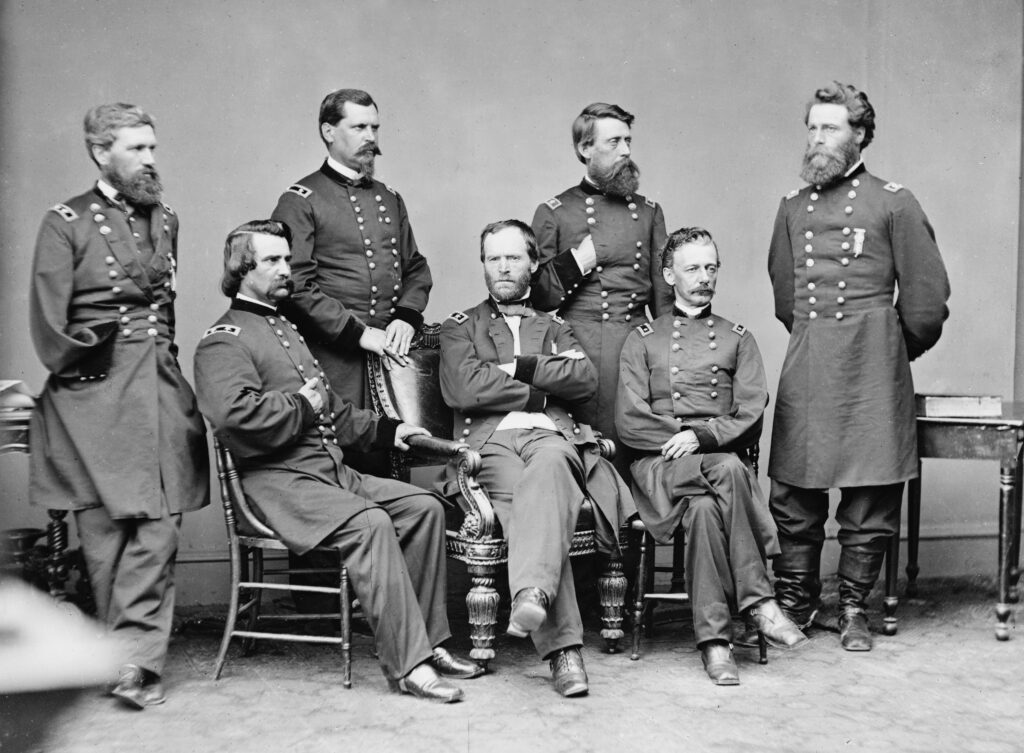

But it was upon his return to service a couple of months later that a new Sherman appeared. No longer nervous or panicky, Sherman was now more decisive. So decisive, people still wondered if he was sane. He became close with Ulysses Grant, a known drunk who was as personally unpredictable as he was tactically brilliant. Together, their military stars rose until Grant was given command of all Union armies, and he dispatched Sherman to capture Atlanta, Savannah, and everything in between. And Sherman did. Three years after being paralyzed by fear, Sherman now confidently commanded an army to burn government buildings, houses, and shops. To destroy infrastructure. To chase people from their homes in terror. And to do all of this from a decided military disadvantage. Sherman’s troops were far behind enemy lines. They had no supply line, so everything they needed to eat, drink, heal with, or shoot needed to be taken as a spoil of war. And despite this disadvantage, Sherman arrived in Savannah and captured it in five weeks. On December 21, when Savannah surrendered to him, he presented President Lincoln with “an early Christmas present”.

Historians have questioned for a decades how Sherman changed so dramatically. The bullet-grazings he took at Bull Run were minimal compared to bullets that would actually lodge in his hand and shoulder at the Battle of Shiloh, his first major battle after his return. In one day at Shiloh, he had three horses shot out from under him. And yet, at night, as he and General Grant sat by the campfire smoking cigars, he claimed to have had a moment of divine inspiration that kept him from mentioning retreat. That night had been a turning point. Because while historians wonder “how” he changed, they could have been asking “why”. In my mind, Sherman’s return from his convalescence found him resigned to get through the war. (Emphasis on the word “through”.) Sherman’s pre-breakdown behavior was not a man trying to “get through”, it was the behavior of a man trying to “get out”. But war is hell, as Sherman would later say. One does not escape the horrors of war by clawing at its walls and averting his eyes from the carnage. One does not complete a war by fearing its millions of horrific outcomes. As Robert Frost said (in war as in life), the best way out is always through. And if William Tecumseh Sherman was ever going to get himself out from under the looming specter of war, he seemed to recognize that throwing himself headfirst into its horrors was the only way out.

Even in the midst of his March to the Sea, Sherman did not command the authority of a born conqueror. He was emotional, irascible, difficult. He seemed to take no joy in the destruction, but also did not seem to feel bad about it. He did not seem particularly proud of the thousands of slaves he had freed who now followed his troops with reverence, yet he noted the significance of the act. His acts were the acts of a man, not a conqueror. A conqueror would be seeking to get in; to take over. Sherman wanted out. And his were acts that any of us can learn from. Because all of us have similar crossings that we need to make. We have demons that we’re locked in a room with. And when it comes time to search for a way out, rarely do we want to consider the path of going “through”. Which makes sense. When we consider Sherman’s path through the horrors of war, we recognize that “through” requires us to face our demons. And years and years of denial and fear and avoidance can make those demons as horrific as the demons of war. Facing them feels like an impossibility, and so we seek cheap avoidances and comfortable rationalizations and skewed perspectives and self-delusion. We claw at the corners of the room, the same way Sherman did, and we pray the demons won’t catch us or break us down. But we fool ourselves. Because we never leave that room. We act and we react and we fumble and the act of “getting away” may consume our lives and empower our demons, but we never get through. We never get through.

The things that damage us the most are the things we need to face the most. They are also the scariest things for us to face. Abuse. Neglect. Shame. Terror. These are the demons we are caged with. And like most people, when I consider my own, I scratch at the windows and doorjambs and look for an escape. But if there’s one thing that inspires me in General William Tecumseh Sherman, it’s the notion that a moment may come when I will decide to “get out by going through”. And when that moment comes, I hope I channel General Sherman. And I hope that I walk that path directly and with my eyes wide open. Because the demons exist, and they have been fed on fear, and now they are large and they will taunt you and feed on you as you make your way out. But Sherman knew that the only way out was through, walking empowered and with eyes wide open.

Demons be damned; I’m getting out of here this time.