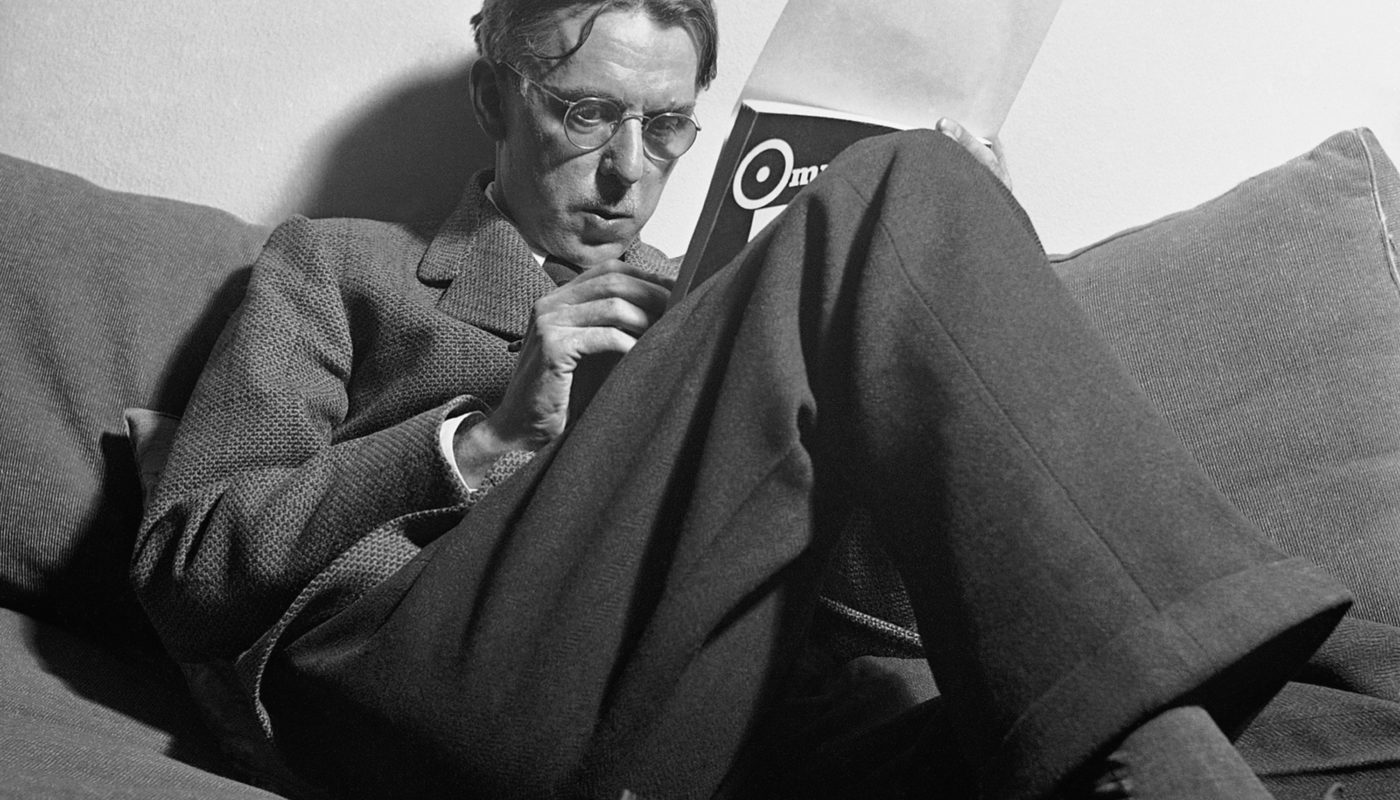

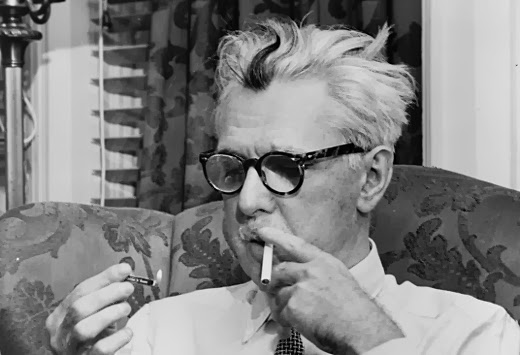

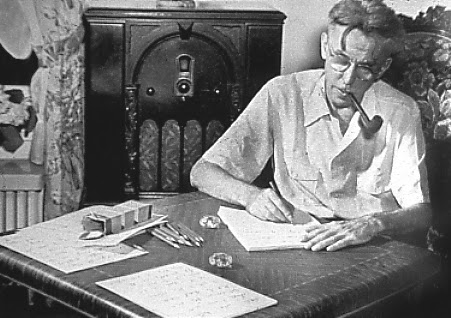

JAMES THURBER: December 8, 1894 – November 2, 1961

The Ohio State University had a long history of important political cartoonists when I joined the staff as a regular cartoonist in 2001. Milt Canniff, Jeff Smith, John “Derf” Backderf, and Nick Anderson all had drawn regular strips for The Lantern. But none of them had impressed upon me the history I was becoming a part of as much as James Thurber. I had first read Thurber in seventh grade, when Mr. Walker assigned us the Thurber short story “The Greatest Man In The World“. It was the first time I remember reading a work of adult literature and “getting it”. In the story, the world is caught up in the fancy of lengthy flights, a la Charles Lindbergh. And a redneck mechanic by the name of “Pal” Smurch develops a crude fueling system that allows him to fly around the world. Unfortunately, his global flight only highlights his crudeness, his lack of education, and his general unwillingness to behave in the ways of polite society. I remember being shocked when the assembled politicians, military leaders, and media moguls “solved” the Pal Smurch PR nightmare – at the orders of the President – by throwing him out of a high-rise window.

To be honest, I read that story in 1982. I have never read it again. But I remember the story and its details more than thirty years later. How Pal Smurch fueled himself on the trip with salami and bootleg grain alcohol. How reporters uncovered a history of violence and petty larceny against both church and state. But mostly, I remember the brisk, unforeseeable change in the narrative when Smurch was unexpectedly tossed from the window to his death. This idea was at the core of much of Thurber’s work: the little man, beset upon by only-slightly-less-little men with higher titles. Whether it be a career man lost in the giant machine of corporate America, a henpecked husband fighting the marital discord of an overbearing wife, or just the simple pack-order maneuverings between men, Thurber was fascinated with the idea of how the little man gets crushed in society. In his stories, they get crushed under the weight of bureaucracy, or under the weight of society, but in reality they all get crushed under the betrayal brought about by their own dreams.

But why did he have this fascination? When Thurber was a young child growing up in Columbus, OH (he is still considered a local legend around here), he was playing “William Tell” with an older brother. Using a bow and arrow, the older brother tried to shoot an apple off Thurber’s head, and instead shot Thurber in the eye. The lack of depth perception caused by the deadened eye would keep him from playing sports as a child, which was – and remains – a vital requirement for “fitting in” in central Ohio. To compensate, Thurber taught himself to draw. And while his cartooning skills were unique, Thurber never mastered line art as completely as he mastered the wit that it supported. Historians have often suggested that Thurber’s early artwork was a result not only of his eye injury, but as a representation of both of his parents. Thurber’s mother was – by Thurber’s account as well as others – an hilarious woman, prone to pranks that would deflate over-inflated egos. Thurber’s father, on the other hand, was the quintessential “little man” of Thurber’s literary work: a dreamer and a drifter who always believed he deserved more than the world ever afforded him. And so James Thurber, with one dead eye and a rapier wit, compensated for his status through art. Sadly, that same eye would disqualify him from a required ROTC course while he was an undergrad at Ohio State, and he was never able to graduate from his hometown university where he discovered and developed both his literary and cartooning talent.

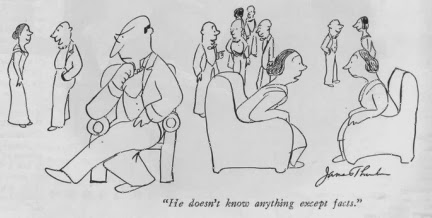

And Thurber’s talent was pronounced. They say that brevity is the soul of wit. Thurber’s brevity (he only drew single-panel cartoons, and he never adopted long-form narrative in his writing) was a reflection of that same drive. Wit is merely cleverness made funny. Thurber was remarkably clever. It’s why we like wit, and why we like witty people. Wit is not a function of wisdom, or even intelligence. It’s clever. And cleverness has the fox’s spirit. It is not the fastest animal, or the strongest. It can not climb trees or swim well. It is too large to burrow quickly or deeply. A fox’s main line of defense is cleverness, and it is why fox hunting is considered a rewarding sport. Thurber viewed the world through a fox’s eyes, always offering the clever insight in shocks and jabs and then scurrying away before a retort could land.

Though the wordiness of this blog might suggest otherwise, I can appreciate the brevity of wit. I’ve always had a love-hate relationship with wit. Namely, it always came easy to me, and was responsible for most (if not all) of my problems in school. (And sometimes work. And sometimes in relationships.) Wit is opportunistic; I always found the well-timed one-liner irresistible, and every report card and every teacher-parent conference mentioned my desire to “entertain” superceding any responsibility towards maintaining class order. By the time I graduated high school, wit was almost treated as a curse – a persistent, disruptive problem to be cured. Because treating another’s wit as a personality trait is easy to do when their cleverness is not focused on us. But when you’re a teacher who can not control a class, or a coach who can not control a team, or a parent who can not wrestle respect out of a kid, cleverness seems like a curse. And for years, I was convinced that the wit of one-liners and brief insights and shock comments was my curse. It was the shallow part of my soul, commandeering moments that could be spent on reflection and wisdom, in the same way they commandeered every boring class I ever had in elementary and high school.

What Thurber shows us is the important role of cleverness. As mentioned earlier, cleverness is opportunistic, and as such, is open for misuse or misunderstanding. There’s a skill to opportunism, an ability to capitalize on moments and cause disruption. But all disruptions are not the same. Dick Cheney is one of the most clever politicians of all time. Not wise, not even necessarily intelligent. Yet his entire political career was based on his ability to capitalize on opportunistic moments to his (and his party’s) advantage. Wit, on the other hand, capitalizes on a moment to shock and to to excite. At its best, it also encourages us to think. At its most effective, we laugh and we remember – sometimes for 30 years – the message we need to hear.It may feel out of control to some, and a lesser art to others, but it remains.

For decades, it remains.