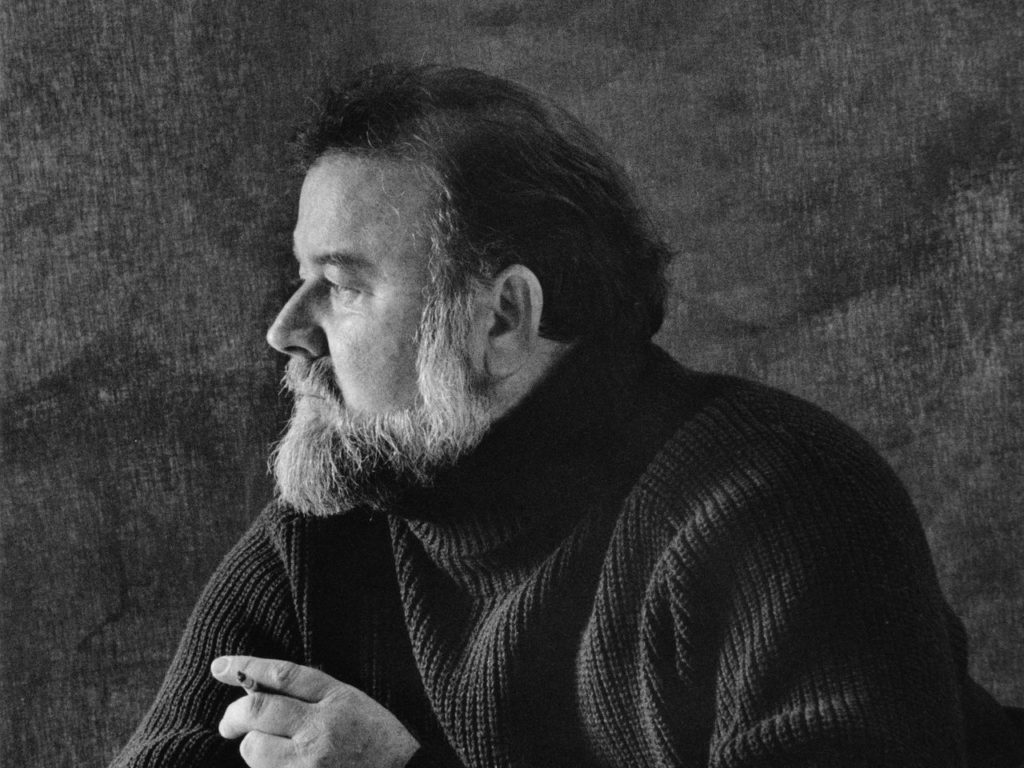

ANDRE DUBUS: August 11, 1936 – February 24, 1999

I had no intention of writing tonight. Like most every night, I planned on finishing up my day with the same self-dismissing review of the day that I go through every night: not enough attention paid to my family, not enough time spent writing or drawing or playing music, another day without exercise, et cetera, et cetera… It’s not a behavior uncommon to me. I am regularly disappointed with myself, to the point that it no longer feels like a failure in behavior, and more a failure of character. I’m not a person who makes stupid choices; I’m a stupid person who makes reasonable choices (for a stupid person). But I was watching the new Chris Farley documentary, I Am Chris Farley,which ended with a prayer Farley carried in his wallet. Farley is another person I’ve long admired (and written about in this blog), so I was touched by the prayer, called “A Clown’s Prayer”:

“Dear Lord, as I stumble through this life, help me to create more laughter than tears; dispense more happiness than gloom; spread more cheer than despair. Never let me become so blasé that I fail to see the wonder in the eyes of a child, or the twinkle in the eyes of the aged. Never let me forget that my work is to cheer people, make them happy, and make them laugh. Never let me acquire success to the point that I discontinue calling on my creator in the hour of need, and acknowledging and thinking him in the hour of plenty. And in my final moment, may I hear you whisper, ‘When you made My people smile, you made Me smile.’”

The prayer made me think of a story that novelist Andre Dubus III told about his father, the writer Andre Dubus. When describing his father’s influence over his own work, Dubus III said, “It’s not his fine work. But seeing him walk daily into his downstairs study in our tiny rented house and try to write something beautiful for someone he would probably never even meet. It’s that image that gave me permission as a young man to view writing as a legitimate line of work to devote one’s life to.” Both stories are reminders that whatever gifts we have are not just gifts for ourselves, like a child’s Christmas toy. The gifts we have are to be shared, and denying those gifts is denying… well, everyone. Which is difficult to reconcile when you love the people who give of themselves, but find it easy to ignore and avoid that path yourself.

It’s ironic that so many Dubus fans discovered him through a comparison to Raymond Carver. This is how I discovered him; a recommendation from an online acquaintance who quoted Dubus’s work, and they reminded me of Carver’s wounded emotional landscape. I immediately went to the library and started reading his short stories. And as much as the writing reminded me of Raymond Carver, I found myself frequently bristling at Dubus’ stories, and I was never sure why. The characters in Raymond Carver’s stories had come to accept their fates as losers, and they had chosen to wear their roles on their sleeves. They’d grown into their roles comfortably, and had stopped trying to buck fate; this was behavior I could understand in my bones. But Dubus’ stories were different, in that the characters looked like losers, but he refused to deny them enough dignity to be branded as such. Dubus’ characters lived in the same world as Carver’s characters – they drank and smoked and fought and married wrong and cheated on their spouses and broke each other’s hearts and let each other down – and the emotional responses were similar. Both Carver and Dubus made a career out of examining flawed relationships and brutality and betrayal and faith and redemption. But in the best situations, Carver’s characters were redeemed from their sins but remained forever branded. Dubus’ characters, on the other hand, were the products of Dubus’ proud devout Catholicism. His characters made mistakes and committed sins, but none were unpardonable. Carver’s characters were doomed, but Dubus’s characters were just temporarily lost.

And that is both the power and the frustration in Dubus’ work. In his novella Voices from the Moon, we follow the family of twelve year-old Richie Stowe, a pre-teen determined to become a Catholic priest. As we get to know the family over the course of the day, we learn that Richie’s father has fallen in love with Richie’s older brother’s ex-wife, and the two plan to marry. And yet, throughout a tale of a father falling in love with his son’s ex-wife, tensions rise and rise until the fateful conflicts where the father must tell his estranged daughter of his affair, and the young son tells his divorced mother of his father’s betrayal. In most literature, the moral lines would be clearly delineated: the father is a monster, the ex-daughter-in-law damaged, the older son is the shamed victim, and the young son is unwitting collateral damage. But not in Dubus’s world. In the story, the estranged daughter acknowledges her own problems with relationships, admits to herself that she is in no position to judge her father, and the two dance to Frank Sinatra music. And Richie’s mother listens to her young son spill the details of the father’s affair and knows immediately that the son will forgive the father. She encourages Richie to move beyond his anger and frustration. “We don’t have to live great lives,” [the ex-wife] says. “We just have to understand and survive the ones we’ve got.”

In Dubus’ short story “Killings”, a grieving father kidnaps his son’s murderer (out on bond, awaiting trial) at gunpoint and forces the murderer to go to his own apartment and pack for a bail-jump. He convinces the murderer that he has arranged a passage out of the area, and that the murderer will need to leave and never return. He convinces the murderer that his wife cannot handle the details of a trial, and a recounting of the jealous rage that led the murderer to shoot their youngest son. The father, however, knows this is all an elaborate scheme, and he intends to execute the murderer and make it look like the murderer skipped bail. But as the murderer packs, the grieving father looks around the apartment, and notices the mundane nature of things. Folded underwear. Rolled socks. A clean stovetop. Typical family photos. Dubus hangs on the obvious, the normal, the typical. And the father recognizes the common ground between the man who has murdered his son in a jealous rage and himself. Neither are truly monsters; they are just ordinary men who have been pushed too far, and reacted poorly. It’s not a world of moral subjectivity, however. Dubus never short-changes the horror of murder or revenge or jealousy. His characters certainly suffer. But none are indefensible, and none or unforgivable. By the end of Dubus’s stories, it’s impossible to hate any of the characters, no matter how despicable their behavior may seem at face value.

And I think that’s what I bristled at Dubus’ work. Not just because his world isn’t black and white. I understand the appeal of a world devoid of nuance, where monsters are irredeemably bad and angels are unsullied and perfect. But Dubus doesn’t simply present a world in shades of grey, he also retains a sense of faith throughout the entire world. Which not only means that the monsters are worthy – and capable – of redemption, but that redemption requires effort. Faith absolves us for our sin, but we need to work towards redemption. We earn forgiveness. We rebuild trust. We calm the waters from the storms we’ve caused and await absolution. And when I’m honest with myself, I’ve always felt more like a Carver character than a Dubus character. Because it’s easier to presume yourself guilty and unforgiveable forever. It’s easier – in the moment – to give up and wear failure like a vestment. It’s easier to expect little or nothing from yourself. And some of us have learned to believe that this is how life should be. To believe that the habits we’ve cultivated and the mistakes we’ve made and the time we’ve wasted are constraints that we’ll never break free from. Dubus doesn’t let us off the hook that easy – in literature or in life. No matter how deep the hole we’ve dug for ourself, Dubus shows us the light at its opening. The light that still streams in, no matter how far we’ve dug.

And so tonight, as I planned to do a little work, fold a little laundry, and surf the Web until I was numb, I considered Andre Dubus. I thought of the idea of writing just to make a stranger smile. And I sat down at the keyboard, and just kept looking for the light, streaming in from where I once started.

A lovely, insightful essay.