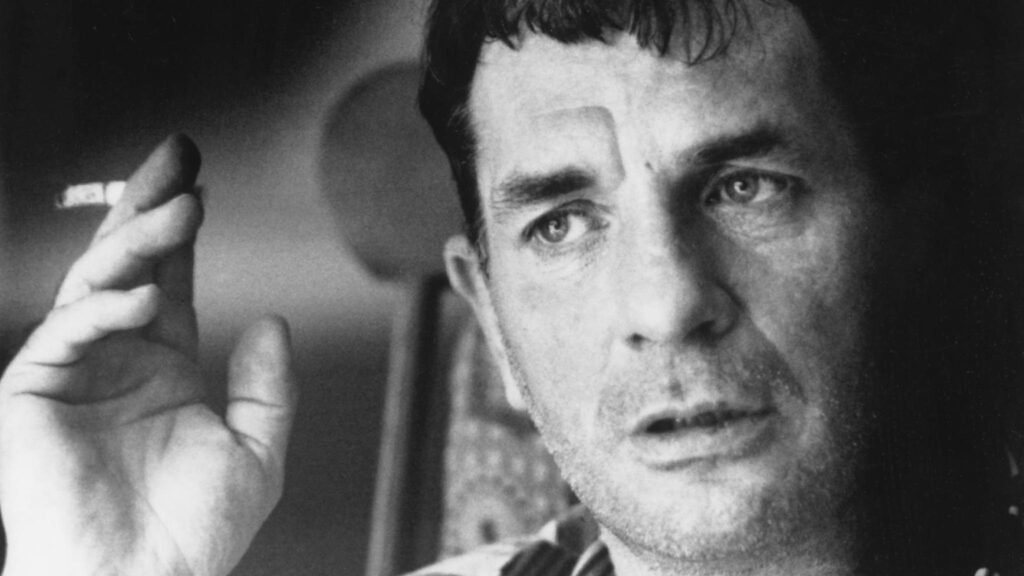

JACK KEROUAC: March 12, 1922 – October 21, 1969

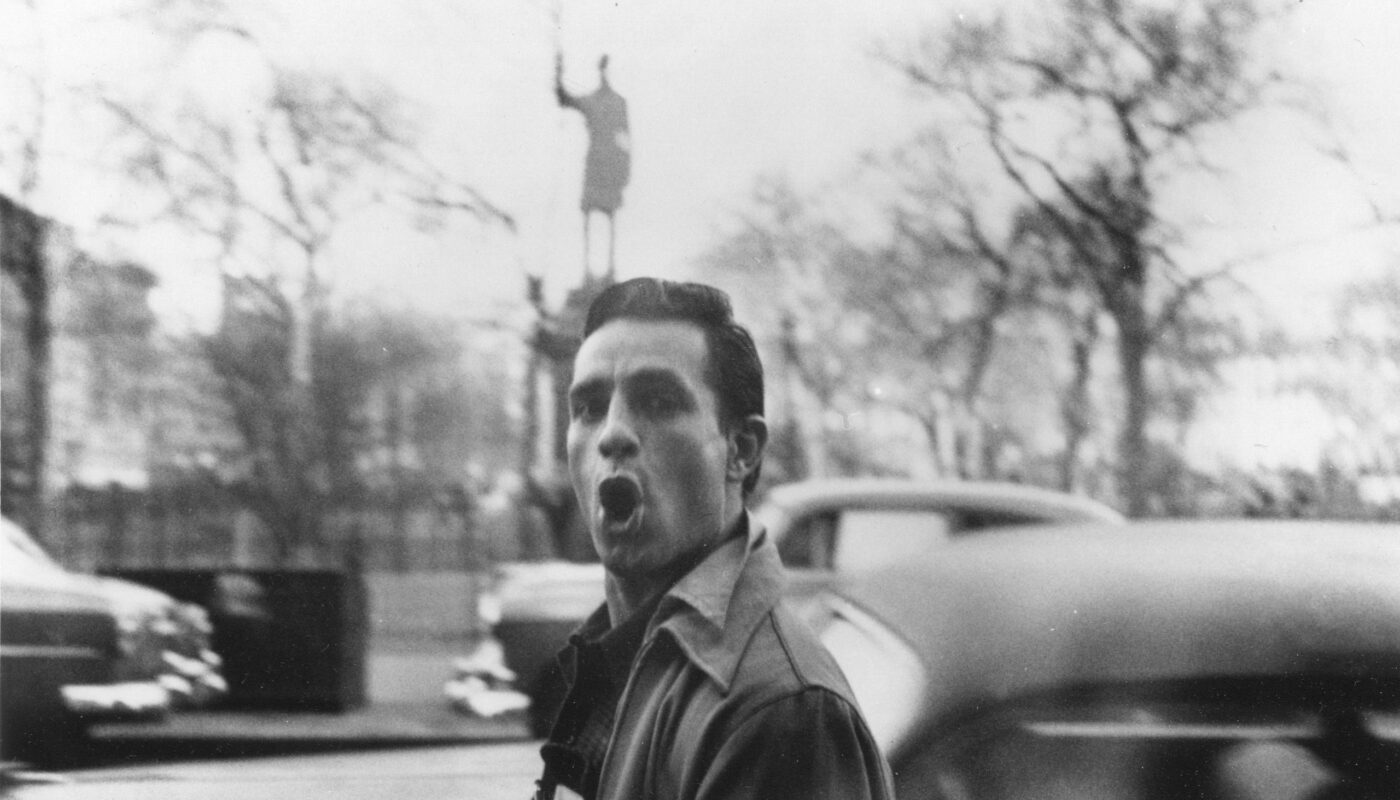

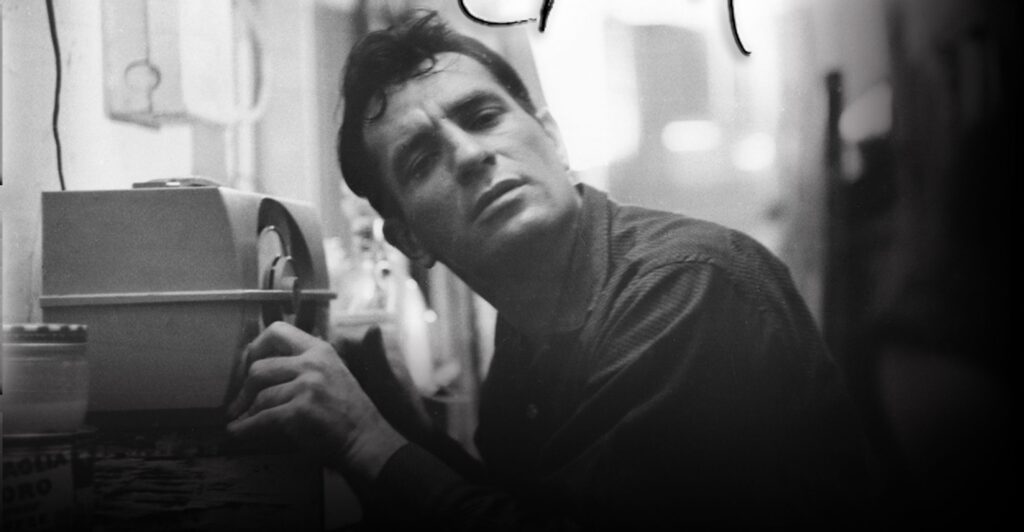

It was my love of neon that introduced me to the work of Jack Kerouac. My family got our first VCR in 1985, and I went to the local library to check out VHS tapes. The selection in the genres typically enjoyed by 15-year old suburban boys was picked thin, and I was looking at documentaries. One of the newer documentaries had a photo of a young man in a wrinkled white shirt and khaki pants standing in front of a large neon sign, his head back and jaw up with a look of defiance. The name of the man, Jack Kerouac, was on the cover. I was interested in the strange name, fascinated by the neon, puzzled by the defiant stance, and curious about the nickname in the film’s title, “King of the Beats”. I took the documentary home and was immediately captivated by Kerouac. The tape was due back at the library a few days later, and I traded it for a hardback copy of On The Road, which I read in about two days. I was a sophomore in high school, but had already taken to skipping classes whenever I could; I had become fairly capable of forging notes in my mother’s handwriting, and I had a couple of friends in their first year of college who could be easily convinced to call the school as my father whenever they were in town. Once I started On The Road, I refused to put it down. I went to school the next morning but just wanted to read the book. At lunch, I forged a note from my mother about an imaginary doctor’s appointment and left school. I sat on the swings of a churchyard playground near my high school and read the rest of the book. Just as Thomas Wolfe had done for Kerouac, the experience changed my outlook on life. I quickly began consuming every Kerouac book I could find.

The obvious initial attraction was the language. Kerouac’s “spontaneous prose” had every element of a good storyteller friend rushing you through a series of adventures from the night before, complete with mash-up words and traffic jams of adjectives and sentences that seem to run on far too long (or derail themselves mid-sentence to go off on a different tangent). On The Road felt honest to me in the way no book before had. Even if I didn’t have any similar experiences to Kerouac’s, I recognized in his voice something I desired. The ability to extemporaneously share thoughts and feelings without any sense of guilt or shame was my vision of a perfect life. That’s why the main lesson that the spontaneous prose of On The Road – and much of Kerouac’s work – communicated had a strong appeal to a kid from a competitive high school in an upper-middle-class white suburb. Jack Kerouac was the first person I’d read who showed me that experience, not accomplishment, could be its own reward. More importantly, if experience was its own reward, accomplishment became a non-factor. At the time I discovered On The Road, I was on a precipice that is common only to a very specific sector of suburbia. As Matt Stone, co-creator of South Park said in an interview about growing up in Littleton, Colorado (where the infamous Columbine High School massacre occurred in 2001):

[Littleton was] just painfully normal. Painfully average… I remember being in sixth grade and I had to take the math test to get into honors math in seventh grade. And [my parents and teachers] were like, ‘Don’t screw this up. Because if you screw this up, you won’t get into honors math in seventh grade. And of course, if you don’t get into honors math in seventh grade, you won’t get into honors math in eighth grade. And then not in ninth grade. And then tenth and eleventh grade. And then you’ll die poor and lonely.’ And that’s it, you know?… They scare you into conforming and doing good in school by saying, ‘If you’re a loser now, you’ll be a loser forever.’

That was exactly where I was living in 1985 and 1986. I was a B+ student in a high school where a B+ average did not put you in the top half of a class of over 500. In my sophomore year, I was – coincidentally – demoted from an honors math class. To my parents, teachers, and counselors, it was the beginning of the end for me. A lifetime of being told I didn’t ever “live up to my potential” was finally becoming a permanent scar instead of a constantly-refreshed wound. Hints were dropped that I should re-consider or amend college plans. I was reminded any time I would discuss future plans that any plans I make would have to be modified and scaled back considerably, given my obvious penchant for failure. I was fifteen.

This was the kind of fertile ground in 1957 that allowed On The Road to help usher in America’s first youth movement. America had always held accomplishment as its measuring stick; our history was written in a Puritan work ethic that measured the grace of God’s love by the size of one’s success. Accomplishment wasn’t just a moral good; you were morally good because you accomplished things. In 1957, in the wake of two victories in consecutive world wars, with one of the greatest economies in the history of the world (due largely in part to European and Asian infrastructures being destroyed by the aforementioned consecutive world wars), America was riding high on its track record of accomplishments. And we had more than enough resources to allow young people to have new experiences. The door was opened for a brief moment, and jazz came in. And rock & roll. Blue jeans. Motorcycles. Marlon Brando and James Dean. And the text that seemed to describe them all was On The Road, a book that New York Times literary critic Gilbert Millstein hailed as “perfect an expression of a generation as Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises“.

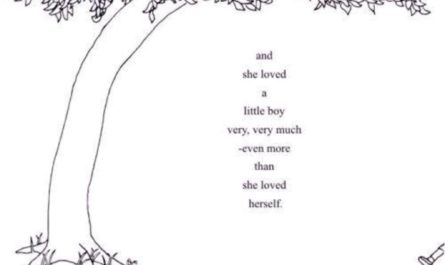

Jack Kerouac gave voice to the simple idea that there is dignity in the pursuit of experience. Unsurprisingly, that message was not met with open arms in 1957. In a literal meta-commentary, Truman Capote – the epitome of an “accomplished” writer of the time – referred to Kerouac’s output as “typing, not writing”. To Kerouac, the nature of his work was in the oft-disputed origin of the moniker “Beat Generation”. Catholic-raised Kerouac insisted for the rest of his life that “Beat” was originally a shortened form of “beatific” – the sublime imparting of holy bliss. (Others claim it referred to a discussion between Kerouac and John Clellon Holmes, who first published the term in his novel Go, where they described their entire generation as “beaten down and furtive”.) To Kerouac, life should be lived in the moment, with its focus on the pleasures and gratitudes and connection and tenderness. A life filled with these blessings didn’t require (or even consider) accomplishment to be fulfilled – it was already overflowing with fulfillment. But this belief system is so contrary to the guiding philosophies of late-stage capitalism in America. To continue that belief in the face of an entire society’s opposition requires total immersion in a philosophy that focuses on being present in every moment, or else it risks disillusionment and corruption. True to form, Kerouac went down both paths.

Within a year of the publication of On The Road, the sudden explosion of fame had left Kerouac unsettled and uncertain. A lifelong Catholic, Kerouac soon found Buddhism’s focus on experiencing each moment in a non-judgmental way meshed very well with his beliefs on the nature of the Beat Generation. The ability to experience every moment objectively and experience the spectrum of emotions without moral attachment (like guilt and shame) was exactly what Kerouac had been looking for. He began to study Eastern philosophy and meditation. His novel The Dharma Bums detailed this period. The book includes my favorite passage by Kerouac. In a scene where Ray Smith (Kerouac) and Japhy Ryder (poet Gary Snyder) go mountain climbing, Ray gets winded and too afraid to keep climbing. He stops to rest on the mountainside while Japhy continues to the crest. As Ray grabs his breath, he hears Japhy from up above.

Then suddenly everything was just like jazz: it happened in one insane second or so: I looked up and saw Japhy running down the mountain in huge twenty-foot leaps, running, leaping, landing with a great drive of his booted heels, bouncing five feet or so, running, then taking another long crazy yelling yodelaying sail down the sides of the world and in that flash I realized it’s impossible to fall off mountains you fool and with a yodel of my own I suddenly got up and began running down the mountain after him doing exactly the same huge leaps, the same fantastic runs and jumps, and in the space of about five minutes I’d guess Japhy Ryder and I (in my sneakers, driving the heels of my sneakers right into sand, rock, boulders, I didn’t care any more I was so anxious to get down out of there) came leaping and yelling like mountain goats or I’d say like Chinese lunatics of a thousand years ago, enough to raise the hair on the head of the meditating Morley by the lake, who said he looked up and saw us flying down and couldn’t believe it. In fact with one of my greatest leaps and loudest screams of joy I came flying right down to the edge of the lake and dug my sneakered heels into the mud and just fell sitting there, glad. Japhy was already taking his shoes off and pouring sand and pebbles out. It was great. I took off my sneakers and poured out a couple of buckets of lava dust and said “Ah Japhy you taught me the final lesson of them all, you can’t fall off a mountain.”

“And that’s what they mean by the saying, When you get to the top of a mountain keep climbing, Smith.”

To me, this moment feels most representative of what Kerouac claimed was the Beat Generation’s divining philosophy. The exuberance of the writing that builds as the characters hurtle themselves down the mountainside joyously is a perfect example of Kerouac’s “beatific” claim. The characters are emboldened by bliss and overcoming longstanding fears; they are literally falling with the faith that their leaps will be safely supported, despite a lifetime of beliefs to the opposite. The accomplishment of Japhy (who reached the peak) is immaterial and barely mentioned. Only the experience and what we learn from it matters.

Sadly, the risk of focusing on experience is that it is easily corrupted. Fairly quickly, the Beat Generation “sold a million pairs of blue jeans and espresso machines”, as William S. Burroughs once said. By 1960, television shows were filled with “beatnik” characters who made the Beat philosophy seem like an excuse for laziness and willful ignorance. Kerouac would later publicly state resentment towards Beat poets like Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who championed the political power of the hippie youth movement of the 60s, and became a creative godfather for that movement in San Francisco during the “Summer of Love”. Kerouac described Beat poets like Ferlinghetti as riding on his coattails. By the late 60s, the struggles of fame, an adult lifetime of alcohol abuse, and the growing politicization of some of his Beat contemporaries had turned Kerouac away from Buddhism and back into conservative Catholicism. He remained drunk all the time, bitter about how “un-American” many of the writers he once called friends had become, and proudly defended the flag and America. He grew increasingly more isolated, moved in with his mother, and drank himself to death just twelve years after the publication of On The Road. He was 47 years old.

When I started this project, I intended it to follow the spontaneous prose tradition of Kerouac. As long as I’ve been writing for an audience, it has always been my favorite way to write. There’s an honesty to the process of sitting and typing that I can’t otherwise reach. And while the editing process can improve my work, more often than not it simply sticks a knife through its heart; I’ve abandoned far more pieces during the editing process than I have ever finished. It’s the Kerouac-inspired commitment to the initial spontaneous thought and the praise (and investigation) of experience that has always guided this project. While gratitude is somewhat transactional (hence, a “debt of gratitude”), that nature is rooted in accomplishment: Artist accomplishes an album, the album moves me, so I extend gratitude to Artist. This was always intended to be more of an examination of the moments within that series of events. The moments of meaning in life. They are moments I spend far too little time appreciating, much less examining. And I rarely share them.

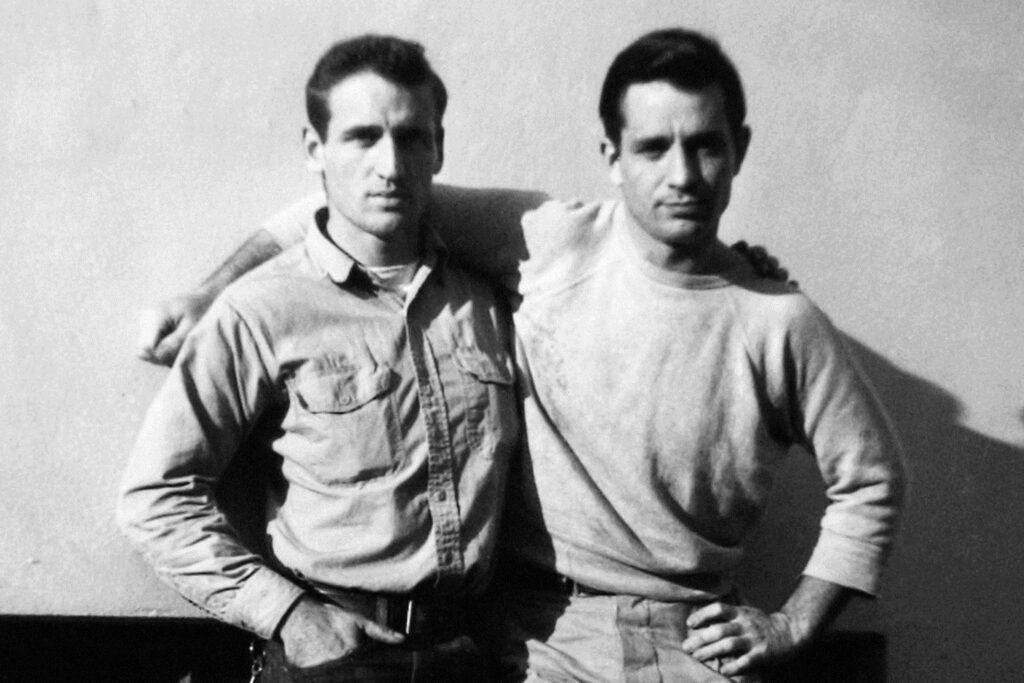

Kerouac described those moments in his most famous quote (from On The Road) about friend Neal Cassady, who was the model for the character Dean Moriarty. Kerouac’s narration doesn’t just dwell on the fun places they’ve been or the blissful things they’ve done (the accomplishments). Instead, he says:

the only people for me are the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars and in the middle you see the blue centerlight pop and everybody goes “Awww!”

That “Awww” is the genesis of this project. We all deserve to recognize it – and revel in the experience – every time it presents itself.