THE ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND: Recorded At Fillmore East, March 12-13, 1971

I had a call with a potential work client last Wednesday that required me to assemble a PowerPoint presentation describing what I do and how I do it. The presentation was in partnership with another (much larger) company that has sales and marketing staff all over the world. But the work we were describing was mine, so I decided to handle the creation of the presentation. Between a full workload and the chronic battle against pandemic isolation-related depression, the added work felt exponential. (Never mind that “trying to describe how I do my work” and “convincing others I’m better than someone else” are two of my weakest abilities.) By the time we met Wednesday morning, I had been awake for 72 of the previous 74 hours. The presentation was about 60% completed to my standards but received unanimously glowing reviews. In a debrief meeting with the partner firm, we discussed how the effort to get ready for the meeting had felt like an uphill battle. It turns out the sales rep I was partnered with had also spent sleepless nights preparing some data for me to incorporate into the presentation.

“I’m sure it could have gone quicker if I had brought someone in to help, but I have real control issues”, he admitted.

I laughed because the one thing that has put noticeable limits on nearly every area of my life, it’s “control issues”. The presentation was a perfect example. I didn’t even know what it needed to say, but I knew I would need it to a specific standard, and I anticipated a fight to get it to that standard. If I’m being honest, any kind of collaboration like that makes me a little crazy; I spend more time trying to guide a collaborator to get the end-product to the standards in my head than if I just handled it alone. The entire process just becomes overly complex and difficult and distancing and frustrating, and the end result is rarely as good as if I just did it myself. Because I can’t describe what goes on during a healthy, productive collaboration. I don’t know how to ask for help. I have difficulty determining whether I need something or want something. I am uncomfortable not assigning intentions to people’s behaviors. All of these shortcomings turn a positive collaboration into an uphill battle.

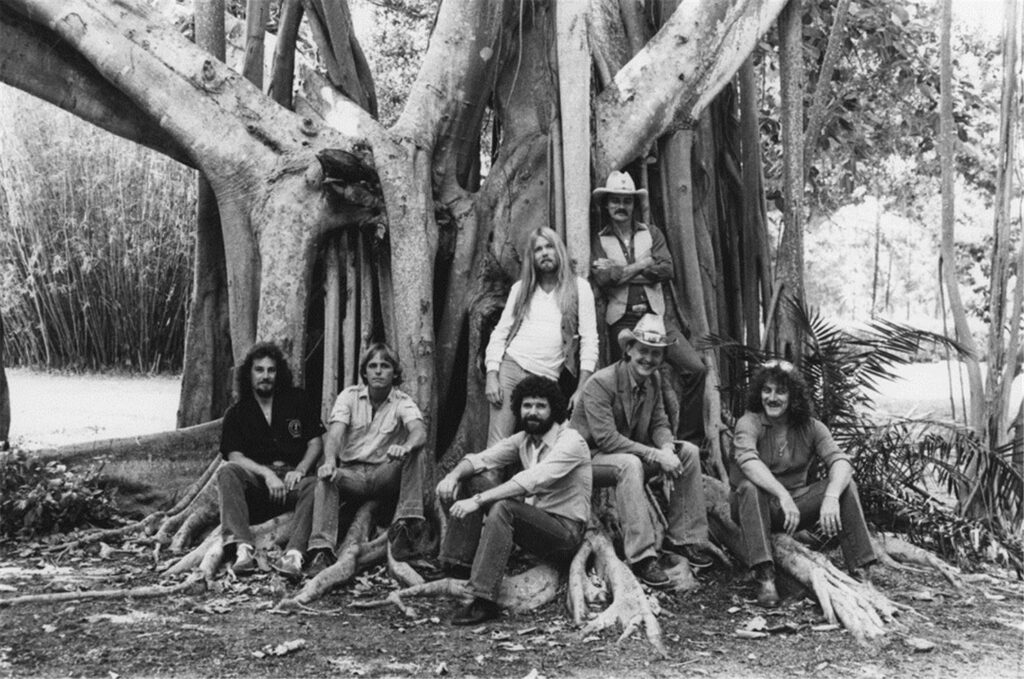

This is not to say I can’t work in a group setting or be part of a team. I played team sports growing up, and I have been in bands. I published a comic book and rode in a motorcycle club. When specific roles are defined and everyone is expected to fulfill their specific duties and not extend beyond those guidelines, I can perform fine. But these are standards of efficiency, not capability. The benefit of collaboration is that it raises the performance of everyone; most successful teams/groups I have been in just allow everyone to perform at their own level, or maybe just slightly below. It’s the difference between any of the road trips in On The Road and taking a platoon of soldiers on a forced march. Both move people from point A to point B, but the similarities stop there. And I have real difficulty understanding how some people can collaborate and create something so far beyond any of their individual talents. But I admire it. So much so, I have an enormous framed photo of one of the most elevated collaborations hanging on the wall of my living room: The Allman Brothers Band.

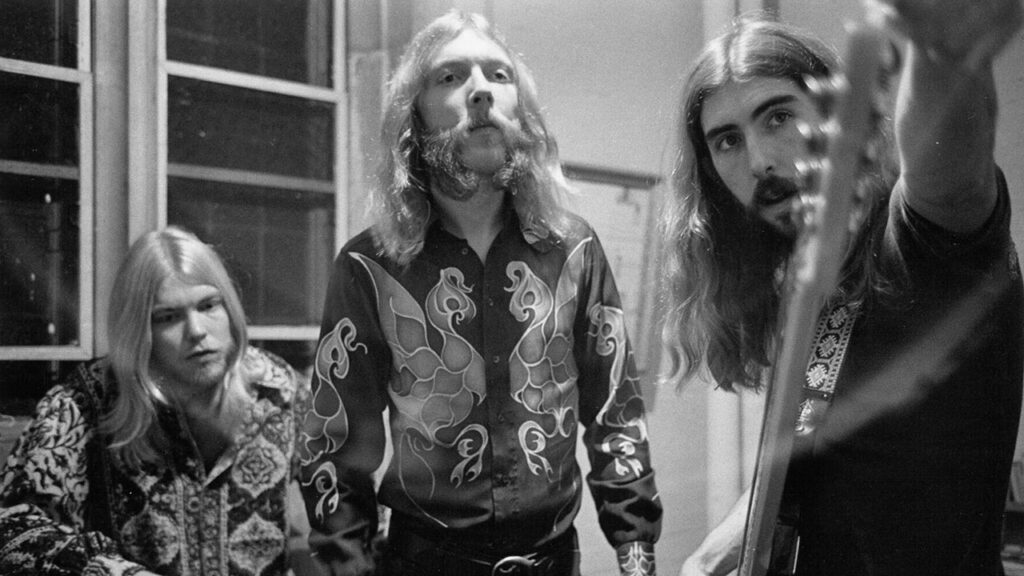

The namesake Allman brothers – Duane and Gregg – were in their late teens when their first band, The Allman Joys (later renamed Hour Glass) was signed to a record label. After a couple of unsuccessful albums, Duane moved down to Muscle Shoals, Alabama, where he would find legendary success as the studio session guitarist at FAME Studios. Within six months of teaching himself slide guitar, Duane was creating some of the most memorable and important guitar leads in R&B and soul history. But he found the strictures at FAME to be too stifling and decided to leave. Otis Redding had recently died in a plane crash and his manager, Phil Walden, was looking to start managing rock acts. Duane left Alabama for a return to Florida and Georgia, playing jam sessions and re-connecting with musician friends along the way. By early 1969, he had found the band he wanted: two lead guitarists (Duane and country-influenced guitar-picker Dickie Betts), two drummers (fellow FAME session player Jai Johanny “Jaimoe” Johanson and Florida drummer Butch Trucks, who had recorded a demo with Gregg and Duane a year earlier on the band name “31st of February”), Macon-area bassist Berry Oakley, and Gregg on vocals and keyboards. The band played their first gig in Jacksonville, Florida, and then quickly moved to Macon to be near Phil Walden.

From the start, The Allman Brothers Band was hard to define. They were a rock band with heavy psychedelic influences, but not really “psychedelic rock”. They were definitely Southern, but not “Southern rock”. They played blues at a level decades beyond their early-twenties, mostly white (except for Jaimoe) upbringing might indicate, but they weren’t a “blues band”. They looked like hippies, but weren’t hippies, either. And instead of relocating to New York City or Los Angeles (or even Chicago), they elected to stay in Macon, GA, which was fine for a Southern R&B singer like Otis Redding (who also grew up near there) but which likely destined a hard-to-classify white rock band for obscurity. It didn’t help that Macon was a heavily-segregated conservative town, and an integrated band of long-haired musicians with plenty of black friends and staff made them local outcasts.

Despite showcasing the immense talent of the band members, sales of their self-titled first album hinted at this possible obscurity. Fewer than 35,000 copies of the album sold. Their second album, Idlewild South, was recorded during a period where the band’s true “brotherhood” ethos was formed. They rented a house, practiced together all day, and either played a gig or threw a party every night. The band learned the style that was Duane’s dream, and it would come to define the band through multiple line-ups for the next fifty years. The band had taken these immense talents, each with its own unique style, and blended it into a cohesive unit that was much, much more than the sum of its parts. But the second album wasn’t able to capture that magic. The Allman Brothers Band traveled the country performing groundbreaking live shows, but they struggled to gain commercial awareness. After months of strenuous touring and unanimously positive critical word-of-mouth for their live shows, the future of the band was uncertain. Eric Clapton was so taken with Duane’s abilities that he invited him to join his newly-formed supergroup Derek & The Dominoes, and the band worried that this might be the end. They were contractually obligated to deliver one more album for Walden’s Capricorn Records, and they decided that the album would be an example of their dynamic live shows. They would record it at Bill Graham’s Fillmore East in New York City, where they regularly drew a packed crowd.

At Fillmore East became the defining album for The Allman Brothers Band and elevated them to their status as the premier jam band of all time. What made them so undeniable was the collaboration. In every band I have ever played in, everyone had their role: the drummer kept the time, the singer sang, the lead guitarist showed off, and the rhythm guitarist and the bassist held the whole thing together. The Allman Brothers Band not only had two lead guitarists and two drummers (after 1990, three drummers), it was designed that way. And each “competing” role was held by a masterful musician in their particular craft. (And let’s not forget the burden on bass players Oakley, Allen Woody, and Oteil Burbridge, who somehow had to wrangle all of these disparate talents into one cohesive unit.) Most bands couldn’t handle that. The roles would instantly become competitive, with each person trying to wrestle the direction of the band towards their own creative vision. Duane Allman understood that if the members in a band could collaborate instead of trying to force the band in their preferred direction, a unique sound would emerge. One that couldn’t be easily classified or labeled, yet enchanted people nonetheless. Why? Because so few bands – and so few people – can do that.

And maybe Duane Allman understood that as he assembled the band he wanted. He knew that two drummers with very similar styles would likely compete, whereas drummers of radically different styles – Jaimoe was a jazz drummer, while Butch was much more of a classic rock & roll “timekeeper” – would learn how (and when) to complement and supplement each other. It’s the tension of opposites that makes The Allman Brothers Band great. But that relationship requires vulnerability. Lots of vulnerability. It requires the ability to trust the band as a whole and suppress any belief that the individual knows the better – or best – path. It requires the message of each song to be the message of the band; each musician makes a unique contribution, but no Allman Brothers Band song is “Duane”s or “Gregg”s. Even signature songs that were written by one member, such as “Midnight Rider” (written by Dickie Betts) was still a great band performance. Even Dickie’s amazing picking throughout the song doesn’t steal the show.

The Allman Brothers Band did, in fact, have periods of poor performance and band drama. Almost every one of them can be explained by a lack of vulnerability. Berry Oakley’s inability to process his grief over Duane’s death. Fights between Dickie and Gregg over who should “take control” of the band. Periods where Dickie would try to steal the show by turning his amps louder than everyone or overplaying solos. Gregg’s unwillingness to confront his addictions. But as each period passed, and the old, vulnerable environment returned, so did the power of The Allman Brothers Band.

So what does it take to allow yourself to experience that level of vulnerability? What does it take to relinquish control? To admit that the direction you want to take may not be the best. Or even more difficult, to willingly go in a direction that you know isn’t as good as yours, simply because the rest of the group is going that way? How do we ask for help? For clarity? How do we suppress our own vulnerability to allow the group to succeed? I can’t pretend to know any of these answers, but I recognize that the ability to answer them yields a much healthier and better product than “control issues” and isolation and a lack of vulnerability.

We just have to find a way to get there. In the meantime, The Allman Brothers Band At Fillmore East can always serve as an inspiration.