ROBERT MAPPLETHORPE: November 4, 1946 – March 9, 1989

We live in a strange time for news. This week alone, there were Senate hearings on the January 6 Capitol insurrection, more hearings to confirm some of the long-overdue Cabinet positions, and extended debate to provide support via the COVID Relief Bill. But if you watch cable news (or get your news from social media), the big news of the week was that the company that manages Dr. Seuss’s library was going to stop publishing six books and that Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head will be packaged in a non-gendered version of the toy simply called “Potato Head”. Comparatively, both stories are little more than page-filler. Seuss Enterprises decided to stop publishing some of its books in response to some calls to de-couple National Reading Week with Dr. Seuss. The books being removed from publication were not popular offerings in his bibliography. (I am a big fan of Dr. Seuss and didn’t recognize two of the titles.) The “Potato Head” announcement does nothing to remove the names, genders, or appearances of Mr. or Mrs. Potato Head; it merely changes the packaging the toy comes in. And yet, people are outraged. At least, they claim to be outraged. What is confusing is… why?

One of the primary fuels of the financial engine that powers the current Information Age is a sense of outrage. People see something that angers or frightens them, the fight-or-flight center of their brain (the amygdala) takes control, the higher cognitive functions are momentarily suppressed or bypassed, and we act. We forward the link to social media with an angry message (“fight”) or we desperately read further with the hope of staving off our inevitable harm or destruction (“flight”). The system is not set up to make it easy, logical, or satisfying to leave the original post and verify the facts. To go to the source and try to comprehend the nuances. To seek out opposing, complementary, or supplementary opinions. Outrage is the starting point and the options are limited from there. (Notice how all of them are designed to keep us on the same site, either refreshing or clicking.) These are the prototypical steps of manipulation; you make someone outraged and inspired to take action, then limit their possible actions into the few that benefit you. I have told my children repeatedly for years, “If someone has to make you angry or afraid to make their point, that person does not have your best interests in mind.” This is not to say that using outrage as a starting point is always a bad thing. If manipulation forces action into a confined set of options, outrageous art forces action into an unconfined world. It inspires you to take action, but it doesn’t require a specific outcome. Instead, it gives the audience the time and the access to knowledge and context required to process the experience. One of the most controversial examples of “outrage first” art was photographer Robert Mapplethorpe.

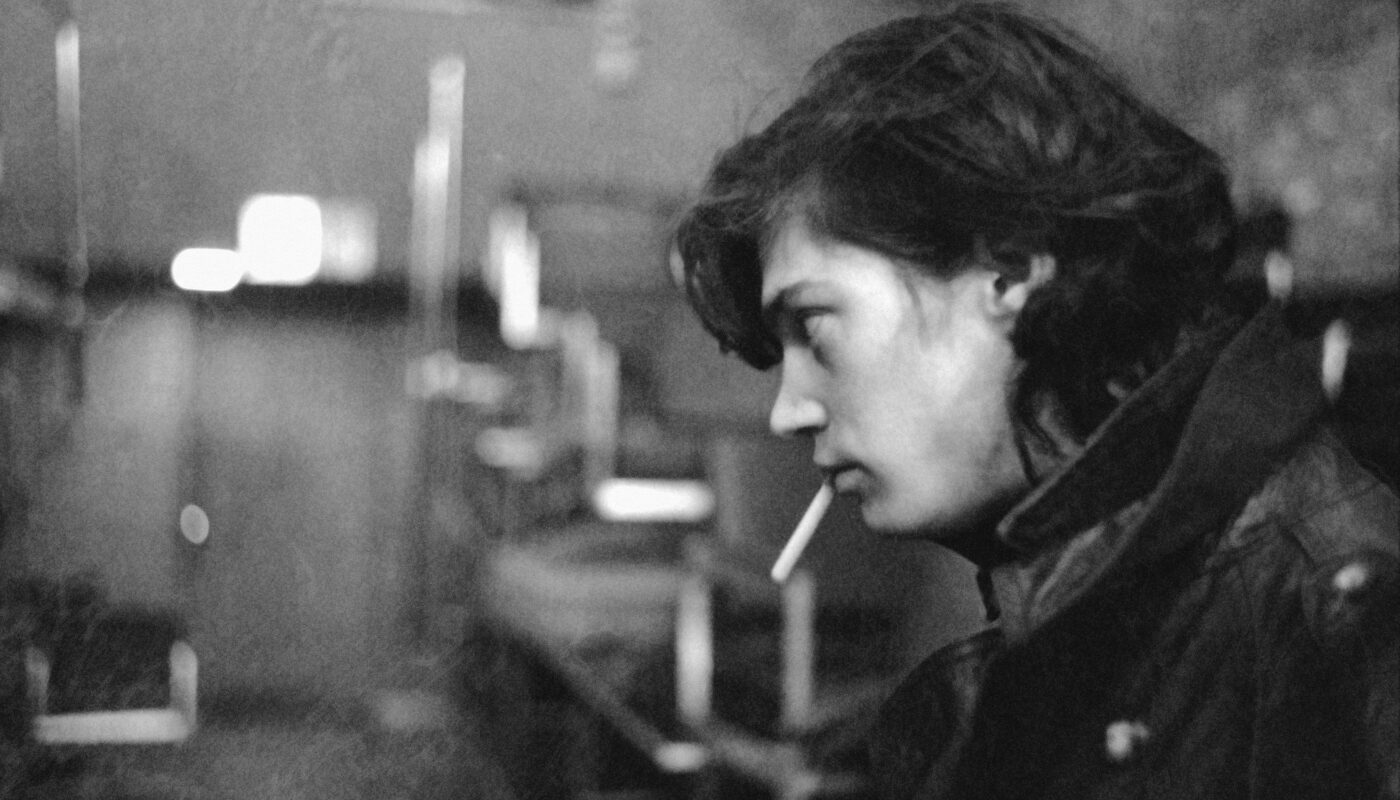

Robert Mapplethorpe had a positive reputation as a black-and-white photographer of flowers and portraits of New York City’s artistic and intellectual elites when he added erotic portraits of the gay male experience to his repertoire around 1977. Mapplethorpe had begun to frequent The Mineshaft, a gay BDSM nightclub. He became such a regular, and took so many photographs, he was given the mock honorary title “Official Mineshaft Photographer”. He began shooting studio portraits of many of the patrons of The Mineshaft in various states of undress and/or BDSM gear. Mapplethorpe’s examination of lighting on the body and the leather/latex/metal gear took on a feeling of “sanctification”. Bodies were lit like marble statues. Bondage gear was lit with the importance of Catholic mementos. Mapplethorpe began to bring in bodybuilders and athletes and filmed them in nude series, like the statutes of David and the Farnese Hercules. It was this period that made Mapplethorpe famous, and while his work would sometimes inspire outrage – there was a sexuality to the photographs that may have offended more delicate sensibilities; charges of racism were sometimes leveled towards some of the poses of POC subjects, particularly at his solo exhibition “Black Males”; and early comments were made about Mapplethorpe’s conservative definition of “beauty” by only shooting attractive, fit models – for the most part, his photos were just gorgeous, captivating studio portraits.

But Mapplethorpe’s fascination with celebrity highlighted how extreme the mind and the creative spirit could go. His flower portraits often showcased how far the beauty of nature could extend. And his portraits pushed at the boundaries of human perfection, trying to capture these examples of the perfect human form in the same way Renaissance sculptors had. But his time photographing the gay and BDSM world of The Mineshaft left his wanting to explore the extent of human sexuality. At the same time, Mapplethorpe had been diagnosed HIV-positive and had begun to feel sick. He curated his next – and likely final – show, The Perfect Moment, which would be a career retrospective. Along with a career-spanning sample of his photos, the show would include three rooms (labeled X, Y, and Z), with each room having its own theme: still-life flower photos, portraits of black male bodies, and BDSM photos (along with two photos that showed exposed children’s genitals). His longtime friend and roommate Patti Smith wrote poems to facilitate the transitions between rooms. The exhibit was launched in late 1988 and was critically and commercially successful in Philadelphia and Chicago. It was being exhibited in Chicago when Mapplethorpe passed away from complications due to AIDS in March of 1989. I went to the show about two weeks after Mapplethorpe died.

The show was scheduled to open in Washington DC’s Corcoran Gallery in June 1989 – with funding from the National Endowment for the Arts – until a group of NEA reps and US Senators were given an advance viewing of the exhibit. They were outraged. Immediately, they demanded the exhibit be pulled. Senator Jesse Helms not only demanded the Corcoran return the NEA funding, but he also doubled down on earlier efforts to dismantle the NEA. The Corcoran Gallery canceled the show, despite loud protests from around the world. The exhibit moved on to Cincinnati, where it opened and was quickly shut down on obscenity charges. The museum’s creative director Dennis Barrie was personally charged with obscenity, as well. It was the end of the exhibit, though ironically, it raised Mapplethorpe’s profile instantly and posthumously elevated him to one of the most valuable artists in the world.

When I saw the exhibit, it was before Mapplethorpe had died and before his worldwide fame exploded. What I remember about the exhibit was how gorgeous the work was. I had seen a Richard Avedon retrospective a few years before and was impressed that Mapplethorpe was equally captivating in his portraits. I also remember experiencing shock (and possibly some outrage) at the BDSM photos. I was a 19-year old hetero white male who grew up in the suburbs. I remember switching between feelings of shock (“Do people really do this??”) and disbelief (“People don’t really do this.”). Because I had zero exposure to anything outside of vanilla suburban straight sexuality, I had no idea if these photos were valid or gratuitous.

If I had to guess, the Senators who shut down the exhibit at the Corcoran Gallery had a very similar sexual history as mine at that time. The difference is that they went into the situation with limited responses. Their options were limited to “do nothing” or “shut down the entire show”. For me, the show left me with the opportunity to reflect on what I’d seen. I had time to wonder and to learn. More importantly, I had time to reflect on why I had been shocked or outraged by the exhibit. Instead of assuming my background and upbringing were the only proper set of behaviors and limiting my responses, I used the experience to question what about my background might merit re-examination.

I suppose this is the distinction between growth and manipulation. The former takes a situation of uncertainty that runs counter to our experience, beliefs, and expectations and inspires us to learn more about the world to make sense of it. Manipulation takes that uncertainty and convinces us that the inciting variable needs to be removed (to sustain the world that consists of only our experience, beliefs, and expectations). Whether it’s the existence of sexuality that we had never considered or the fact that a toy is being renamed in lockstep with a worldview that is changing differently from our own, the sense of shock or outrage can be handled two ways. Sadly, the algorithms and business models that drive so much of this age will lead you towards manipulation. But the simple act of giving ourselves some time – time to stop, to reflect, to ask ourselves questions, to seek answers – can be far more rewarding than taking the bait and leaning into the anger with clicks and forwards and nasty comments. If there is a piece of advice that I believe will make a huge amount of difference in this world, it’s simply “take a moment”. As I told my kids, “if someone has to make you angry or afraid to make their point, that person does not have your best interest in mind.” Note that I never told them if someone does make you angry or afraid. Fear and anger are not exclusively manipulated. But true growth opportunities do not require us to stay angry or afraid. A few minutes after the initial shock of the Dr. Seuss announcement leads to multiple realities. “These aren’t even books people regularly read.” “These aren’t being ‘canceled’, they’re just not being published.” All of the realizations serve to allay the anger and replace it with reason. Any reasonable argument would allow for that amount of time – even welcome it.

And it’s in those moments between outrage and action that so much of our humanity lies. It is in those moments when we decide whether we will learn to grow and understand Robert Mapplethorpe or sow confusion and antagonism in the attempt to stop him. I wish everyone could find the extra moments and the momentary patience to pursue the former. The latter is simply too easy and simplistic to ever help in any way.