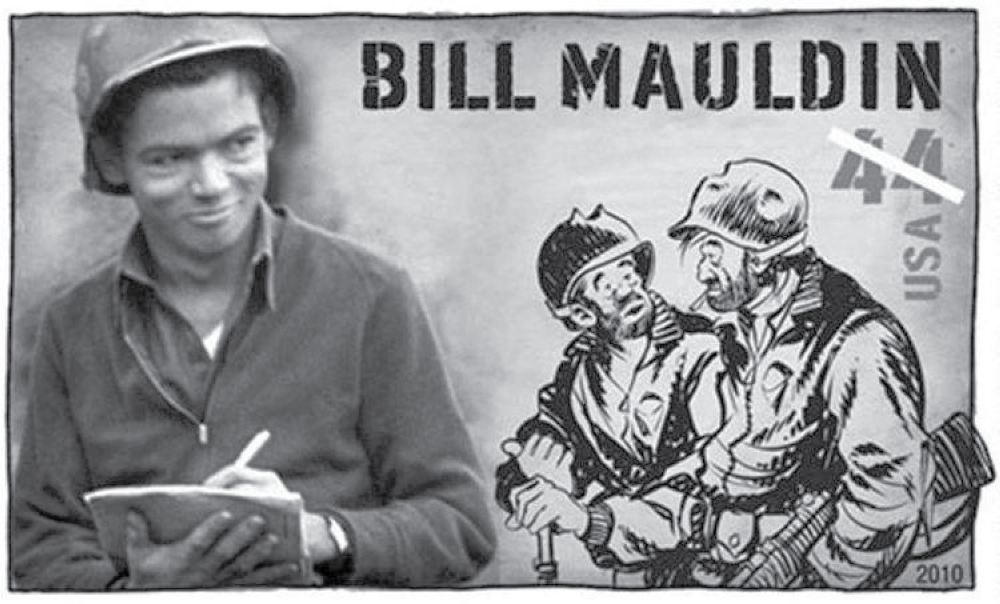

Bill Mauldin: October 29, 1921 – January 22, 2003

When my great-uncle Jack’s landing watercraft approached Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944, a superior officer explained a few of the rules. The water was choppier than they had anticipated, and so water would likely be above their heads. He asked if any of the infantrymen did not know how to swim, and a few men raised their hands to admit they could not. The officer quickly gave a pantomimed demonstration of how to swim, just moments before the gates of the craft would drop and all soldiers on board were expected to storm the beach. Seconds before dispatching, the officer gave one final piece of advice: the beach was covered with defenses – large timber poles, garlanded with barbed wire – and casualties would be strung up in the barbed wire. Some were gravely injured, many would be dead. He warned that German infantry would intentionally shoot at the snared corpses in an attempt to draw out appalled, sympathetic soldiers. Soldiers who couldn’t stand to see the indignity of a fallen comrade being mutilated and destroyed. The goal was to draw these soldiers out to cut these bodies loose and make themselves sitting ducks. “Whatever you do,” Jack was warned, “do not try to cut one of these men loose!” The gate of the craft dropped, Jack made his way through the choppy water and onto the beach. There he saw a dead soldier trapped in barbed wire, his corpse being intermittently punished with bullets.

And so my uncle Jack stood up, went over to the soldier’s body, began to cut him loose, and within a few seconds was shot through the stomach.

The irony of my uncle Jack’s behavior was that it was similar behavior to what was happening all over Omaha Beach. And Utah, Juno, and Gold Beach. The invasion of Normandy was not going as smoothly as planned, and yet Allied forces continued to make headway. Parachutists had been carried off by heavy winds, glider pilots had missed their targets, soldiers found themselves in locations they were not supposed to be, and yet each of them made the most of the situation. Germans soldiers finding themselves out of position or in an unplanned for situation had been trained to wait for their orders. American soldiers, on the other hand, grabbed everything at their disposal, threw caution and direct orders to the wind, and used their best judgment. It wasn’t pretty, and it flew in the face of centuries of military tradition. And yet it worked. Because soldiers like my uncle Jack were common during World War II, despite what the media might have tried to portray. They were a new kind of soldier, and nobody shone the spotlight on this new kind of GI like cartoonist Bill Mauldin.

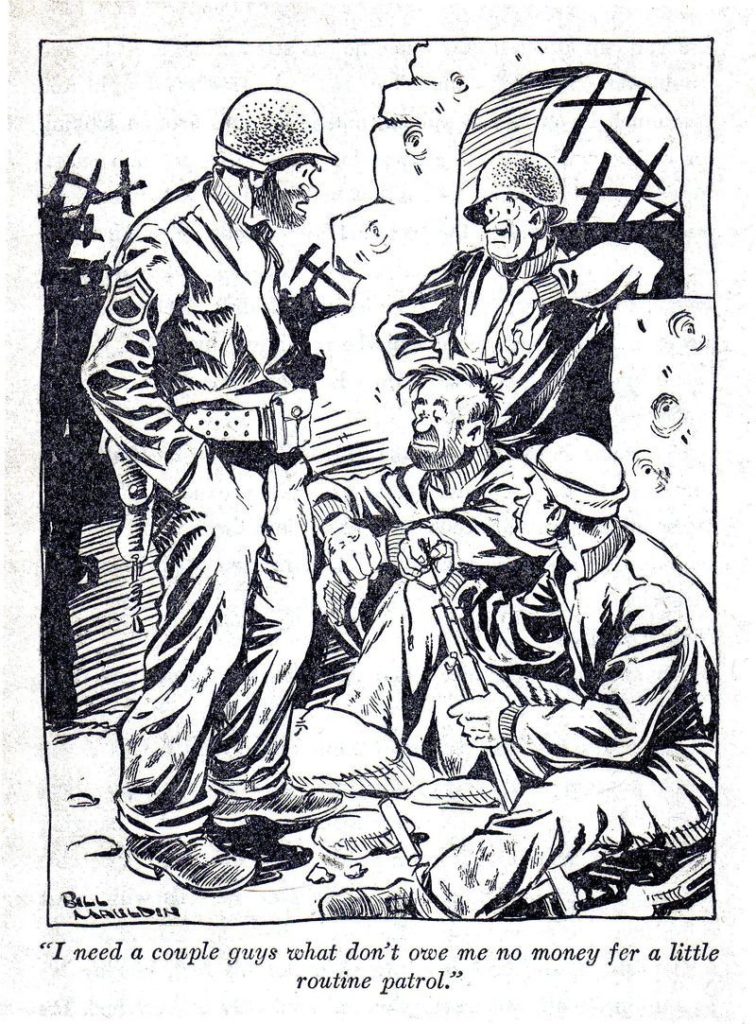

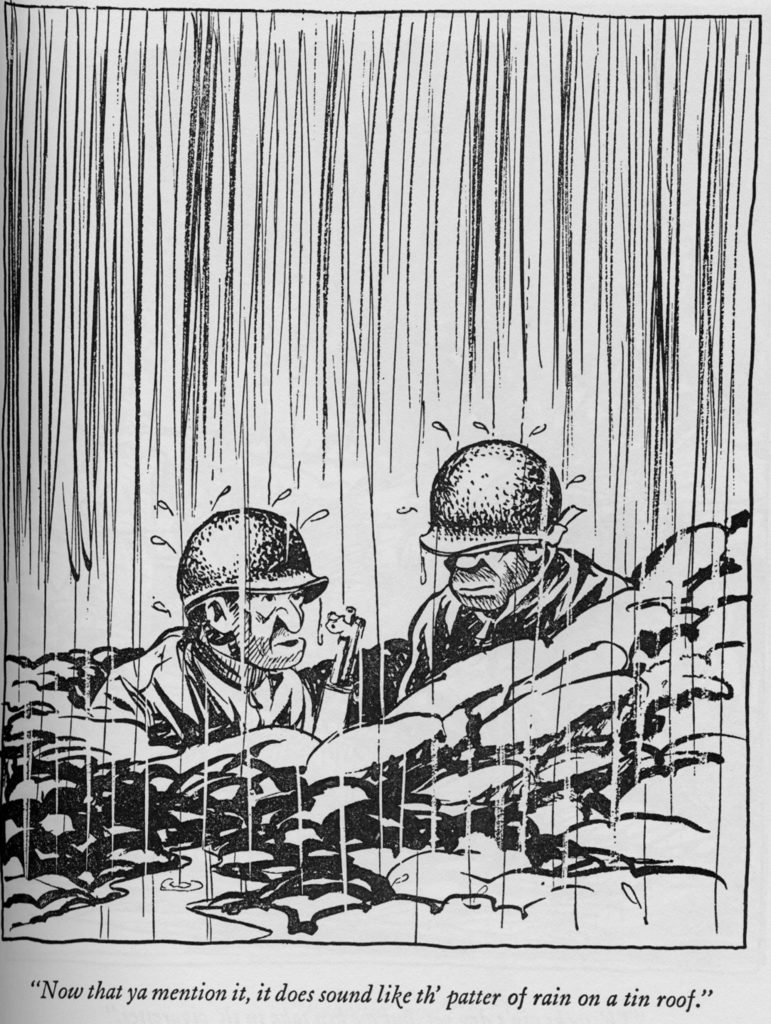

Bill Mauldin was a 23-year old infantryman in the 45th Infantry Division when he volunteered to work on the Division newspaper. He had studied at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, and was quickly given the job of drawing cartoons for the paper. He soon created two characters, Willie and Joe, who were typical GIs of the day: unshaven, unkempt, unconcerned with polite language or proper grammar. They were simply two everyman “dogfaces” doing their jobs, with no concern for decorum. Willie and Joe quickly became so popular with the infantrymen overseas that Mauldin was hired to draw for Stars & Stripes. Eventually, he was given his own Jeep and told to drive around and gather ideas. Often spending time on the front lines with infantry divisions, Mauldin regularly filed six cartoons a week with Stars & Stripes. Eventually, his work was picked up by numerous American press outlets and shared across the nation.

But Mauldin’s popularity was unique, because it ran contrary to the conventional narrative Americans were being fed about the soldiers overseas. Magazines and news outlets shared images of American soldiers that may have seemed battle-wearied and worn down, but generally, soldiers seemed like strict adherents to military regulations. Any break from that adherence was a momentary lapse, usually due to life-threatening circumstances. The war movies that were so popular at the time were loaded with veterans who were grizzled and worn, but still not independent. The narrative of the nation at that time was that our soldiers were liberators: clean, educated, straight young men fighting a morally justifiable war. Screening processes for men volunteering for service ensured they could read, explicitly asked if they liked women (men could be turned away for not answering that question “correctly”, which relied on screeners to judge how much gusto the volunteer put into his answer), and would even deny volunteers for having too many missing teeth. The standards set by the military were designed to not only create a strong fighting force, but a presentable one, as well. The American media picked up on that narrative and ran with it. Mauldin, on the other hand, trampled all over it. Willie and Joe were regularly filthy, and regularly talked about their wretched body odors. At a time when showing a toilet in film was forbidden, Mauldin regularly released cartoons talking about toileting conditions in the field. Willie and Joe were everything we didn’t want to know about our soldiers – and certainly, Mauldin received volumes of criticism for his portrayal of American soldiers – but that we recognized as more honest than most portrayals.

The narratives we create to define ourselves are a study in trade-offs. On one hand, they cut through the complexity of life and define us clearly. On the other hand, they dramatically limit us. And in our attempts to whittle our existence down to an essential definition, we have to discard many important factors about who we are. In an attempt to portray soldiers as fresh-faced pillars of morality who were fighting the good fight for love of country and their “special gal back home”, we denied things that made those soldiers human. We denied the innovation and self-reliance that forced my uncle Jack to risk his life for the honor of a fallen comrade and eventually helped make the invasion of Normandy a success. We also denied the worst parts of that story, like the epidemic of rapes by US soldiers in and around Normandy in the summer and fall of 1944. (It was only in the last couple of years that historians have found American publishers who would print books on that subject. Robert Lilly’s thoroughly-researched Taken By Force had to be published by French publishers who felt the story deserved to be told. No American publisher would touch the book because it was deemed far too controversial for American audiences… more than 60 years after the war had ended.) We create narratives which allow us to pigeonhole ourselves in a positive and productive light, albeit not an honest one.

Bill Mauldin’s cartoons did what the greatest works of fiction do – it created a fabric of lies that was ultimately more honest than the narratives we clung to as a nation. Willie and Joe may have been part of “The Greatest Generation”, but they were also human. Every soldier was. And while some were fresh-faced, apple pie-loving poster boys for America, others were monsters. And most fell somewhere in between. It’s a struggle most of us face on an individual level. We want to believe ourselves to be a specific person, but that narrative is a limited version of who we are. We’re never as simple as the stories we tell ourselves. Our lives aren’t limited to our career or our weight or high school football glory or the abuse we suffered as children. As humans, we’re more complex than our narratives could ever account for. And while breaking from that complexity may have unintended consequences like a bullet to the stomach, it is also powerful enough to win a seemingly impossible battles. But for us to face those battles, we need reminders like Bill Mauldin. Reminding us that our stories are just stories, and they’re not complete. Filling our lives with honesty. Showing us that we’re capable of winning the battles we don’t think we can win, by fighting the battles we didn’t know could be fought.